To kick off the Christmas theme for December, I thought I would give you a couple of mincemeat recipes – one sixteenth and one nineteenth century. They cenrtainly different from the Robinson’s jarred stuff my Mum used when I was a child. Robinson’s were a strange brand of preserves with a ‘Golly’ mascot that was still being used in the 2000s. It’s a long story of how this was allowed that requires a whole entry to itself I think…

Modern day mincemeat is a preserve of sugar, dried fruits, nuts and suet used to fill mince pies. It is certainly in no way meaty. In fact, I think vegetarian suet used these days. The further back you travel in time however, the more meaty the recipes become. Originally, the idea was to make a pie filled with minced meat, heavily flavoured with spices and dried fruits. There were two main reasons for this; first it allowed one to show off about how much spice one could afford; and second, the sweet aromatics could overpower any meat that was past its prime. To show you what I mean, here’s how ‘to bake the humbles of a deer’ from The Good Housewife’s Jewel by Thomas Dawson from 1598 (the humbles are the innards by the way):

Mince them very small and season them with salt and pepper, cinnamon and ginger, and sugar if you will, and cloves, mace, dates, and currants and, if you will, mince almonds, and put unto them. When it is baked you must put in fine fat, and sugar, cinnamon and ginger and let it boil. When it is minced put them together.

The last sentence is puzzling, but it seems to be a recipe that is possible to do these days, though in sixteenth century cook books there are never quantities mentioned.

The same cannot be said for the next recipe from Mrs Isabella Beeton. Mrs Beeton was the first recipe writer to have the great idea of listing the ingredients and the quantities before the recipe. In her magnum opus of 1888, Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management, she included recipes for a regular one, an American one and an ‘excellent’ one. I have never tried the latter two recipes, but the regular one makes the best mince pies I have ever eaten in my life, so if you are thing of making your own mincemeat I urge you to give this one a go. It does contain beef which shouldn’t put you off as you can’t taste it, but it does give it amazing delicious qualities. The quanitities Mrs Beeton gives are huge, so it is best to half or even quarter them. Here they are:

2 lbs raisins

3 lbs currants

1 1/2 lbs of lean beeef such as rump

3 lbs of suet – fresh is best, put the packet stuff is also good

2 pounds of soft dark brown sugar

6 oz mixed candied citrus peel (cintron, lemon, orange &c)

1 nutmeg, grated

2 lbs of tart apples such as Cox’s Orange pippins, peeled, cored and grated

the zest of 2 lemons and the juice of one

1/2 pint of brandy

Mince the beef and suet (or get your butcher to do it).

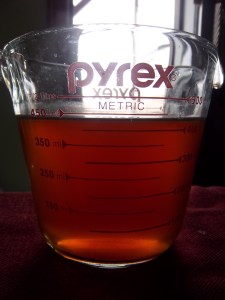

Then, mix all the remaining ingredients together well and pot into sterilised jars, making sure you push it down well to exclude any trapped air bubbles. Leave for at least 2 weeks before you use it. In a couple of weeks, I’ll give you recipe to make the perfect mince pie…

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.