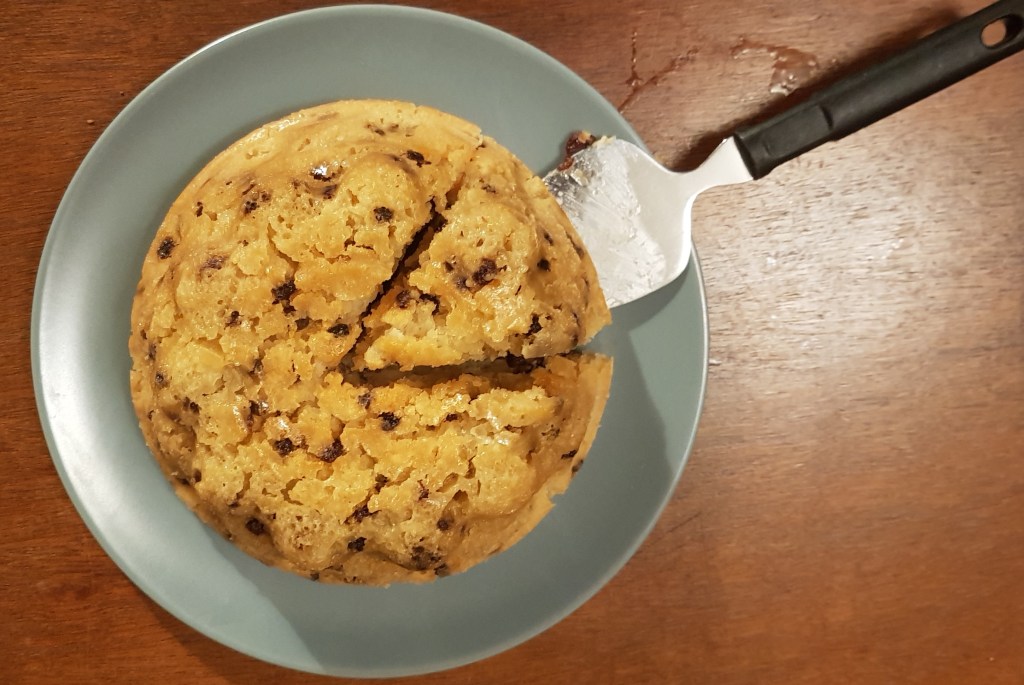

Ah, Yorkshire. God’s Own Country and my home county (well, it’s 3 counties technically, but let’s not worry about that now). There are many delicious regional recipes to be found there, but this must be the best: Yorkshire curd tart. For some very strange reason it hasn’t really ever made its way out of Yorkshire. Essentially it is a baked cheesecake – something that Britain isn’t considered famous for, yet if you delve into the old cook books, you’ll find loads of recipes for them. The cheese in question here is, of course, curd cheese which is sweetened with sugar, and mixed with currants, allspice and sometimes rosewater.

Now a few guiding words on the making of a curd tart: no matter what you read, and I want to be very clear on this, cottage cheese cannot be used. It must be curd cheese which is very different in taste and texture to cottage cheese. These days it is difficult to get your hands on it, but it is very easy to make yourself, as you’ll see below. Also, the only spice to be used must be ground allspice (or clove-pepper as it used to be called in Yorkshire). Not cinnamon, not nutmeg, and certainly not mixed spice. Another misconception is that lemon curd is spread on the pastry base of the tart. Well it’s not, Mr Michelin Guide. Lastly, and as already mentioned, it’s a kind of cheesecake, and not some kind of custard tart as some people seem to think (Mr Paul Hollywood, I’m looking at you).

Ok. Good. Glad we got those issues out of the way.

Curd tarts were traditionally made around Whitsuntide from left-over curds from the cheese-making process and seem to originate in the early-to-mid 17th century. Most families kept their own cow in those days. For those of you that don’t know (and who does?), Whitsuntide derives from the words White Sunday which is our name for Pentecost, which, if my memory serves me correctly, is the seventh Sunday after Easter. The important thing is that there’s a Bank Holiday the next day and a whole week off for half term for the schoolkids.

In dairy farms with several cows, special curd tarts would be made after the cows had calved, using the cows’ colostrum to make the curd for the tarts. Colostrum is the milk produced straight after a mammal gives birth. It is particularly rich in nutrients and fat, and is yellowish in colour. I’ve always thought of this as a bit mean of the dairy farmer’s wife, but then again, she’d also have to tuck into umbilical cord pie the next day, so I suppose it evens out.

To Make Curd Cheese

It’s really easy to make your own curd cheese. All you need is some gold top Channel Island milk, some rennet, salt, and some muslin or other cloth to drain the whey from the curds; I have used an old pillowcase in the past with much success.

Rennet is an enzyme that curdles milk. In the old days a piece of a freshly-slaughtered male calf’s stomach lining would have been popped into the milk (as still occurs in the production of some non-vegetarian cheeses). These days with the magic of science, we can produce it from bacterial culture.

This recipe makes around 750g curd cheese.

In a saucepan, warm a litre of Channel Island milk to 37⁰C, also termed ‘blood-heat’. Use a thermometer if you like. Pour the milk into a dish or bowl and stir in half a teaspoon of salt and your rennet. Follow the instructions on the bottle to see how much to add, as different brands vary. Stir it in, along with half a teaspoon of salt.

Leave the milk to stand for 10 or 15 minutes. Upon your return, you’ll see that the milk had gone all wobbly and can be easily – and satisfyingly – broken into curds.

Scald your straining cloth with water straight from the kettle, spread it out over a bowl so the edges hang over, and then pour in your curds and whey. Tie up the cloth with string and hang up the cheese above the bowl to strain for 4 or 5 hours. Hey presto! You have made curd cheese. It keeps for several days covered in the fridge.

To Make a Yorkshire Curd Tart

Here’s the recipe I use which is based on the one that appears in Jane Grigson’s English Food. It makes enough filling for one 10 inch diameter tart tin, though you can make several small ones if you prefer. The recipe only requires 250g of cheese, so if you’re making your own, you might want to adjust the quantities in the recipe above, or just make three tarts.

The tart is not overly sweet and has a lovely soft centre and a golden brown colour.

125g salted butter

60g caster sugar

250g curd cheese

125g raisins

pinch of salt

2 eggs, beaten

¼ to ½ tsp ground allspice

1 tsp rosewater (optional).

blind-baked 10 inch shortcrust pastry shell (made or bought)

First of all, cream together the butter and sugar well, then mix in the cheese, raisins, salt and eggs. Season to taste with the allspice and rosewater.

Pour the filling into the pastry shell and bake for 25 to 30 minutes at 220⁰C. Cool on a rack.

If you like the content I make for the blogs and podcast, please consider supporting me by buying me a virtual coffee, pint or even a subscription : just click on this link.