Tomorrow is Good Friday and in England it is traditional to eat hot cross buns, or rather it was; supermarkets and bakeries bring them out as soon as Christmas is over these days. And why not? They are delicious after all. The reason that Good Friday is the day these buns are traditionally baked goes back to Tudor times, when the sale of spiced buns was illegal, except on Good Friday, at Christmas and at funerals.

The cross, people assume, is to denote the cross upon which Jesus was crucified. This is in fact nonsense; spiced buns with crosses were being produced throughout much of pagan Europe. Spiced buns have always been symbolic in worship and ones adorned with crosses were made for the goddess Eostre (where Easter get its name).

The Pagan goddess, Eostra

So that is the cross taken care of, but what about the hot? We don’t actually eat them hot that often. They were simply called cross buns, until that famous nursery rhyme was written sometime in the eighteenth century:

Hot cross buns, hot cross buns!

One ha’penny, two ha’penny, hot cross buns!

If you have no daughters, give them to your sons,

One ha’penny, two ha’penny, hot cross buns!

What if you have neither sons nor daughters? I suppose you eat them all to yourself like the miserable old spinster you are…

Ever since I started baking my own bread, I have sworn never to buy it again as it is just so delicious. Bought buns – like bread – are just shadow of their former selves, says Jane Grigson: ‘Until you make spiced hot cross buns yourself…it is difficult to understand why they should have become popular. Bought, they taste so dull. Modern commerce has taken them over, and, in the interests of cheapness, reduced the delicious ingredients to a minimum – no butter, little egg, too much yellow colouring, not enough spice, too few currants and bits of peel, a stodgy texture instead of a rich, light softness. In other words, buns are now a doughy filler for children.’

The recipe below asks for mixed spice, you buy a proprietary blend of course or make your own. I decided to make my own – simply because I didn’t have any. The good thing about making your own is that you can remove spices you don’t like, and enhance the ones you do. Typical spices are the warm ones: cinnamon, mace, allspice (pimento), nutmeg, cloves and ginger. I also think a little black pepper is good.

Here’s my recipe. It makes between 8 and 12 buns, depending upon how large you want to make them. The piped pastry cross is optional – cutting crosses with a serrated knife is fine, and closer to the original. I used to think the same as Elizabeth David, in that they ‘involve unnecessary fiddly work’, but that’s because I couldn’t get them right, I reckon to have worked it out now.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

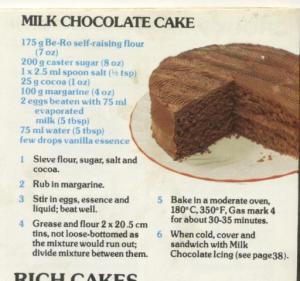

Ingredients

500 g strong bread flour

5 g dried, fast-action yeast

10 g salt

60 g caster or soft dark brown sugar

1 tsp mixed spice

50 g softened butter

250 ml warm milk, or half-and-half water and milk

1 egg

100 g dried fruit (currants, raisins, sultanas, etc.)

25 g candied peel

For the crosses:

50g strong white flour

70-80 ml water

For the glaze:

60g sugar

70 ml water

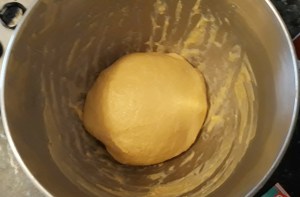

Mix together the flour, yeast, salt, sugar and mixed spice in a bowl, then make a well in the centre. Beat an egg into the milk, and pour it into the well, adding the butter too. If you have an electric mixer, use the dough-hook attachment and mix slowly until everything is incorporated, then turn the speed up a couple of notches and knead for around 6 minutes. The dough should be tacky, glossy, smooth and stretchy. If you don’t have one, get stuck in with your hands and knead by hand on a lightly-floured worktop. It’s a very sticky dough at first, so it’s a messy job, but it will come together.

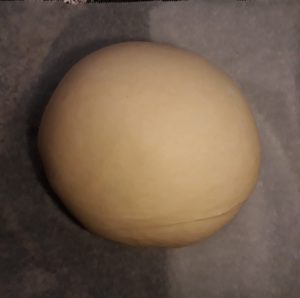

Grease a bowl, tighten the dough into a ball, pop it in and cover the bowl with cling film or a damp tea towel. Leave to prove until doubled in size – this can take anywhere between 1 and 3 hours, depending upon ambient temperature.

Knock back the dough to remove any air and mix in the dried and candied fruits – again, either by using your hands or your dough hook. Divide the dough into 8, 10 or 12 equally sized pieces and roll up into very tight balls on a very lightly-floured board. This is done by cupping your hand over a ball of dough and rolling it in tight circles, takes a little practise, but is an easy technique to learn.

Line a baking tray with greaseproof paper and arrange the buns on it, leaving a good couple of centimetres distance between each one. Cover with a large plastic bag and allow to prove again until they have doubled in size.

Meanwhile, make the cross dough. Simply beat the water into the flour to make a loose, but still pipeable batter. Put the batter in a piping bag (or freezer bag, with a corner cut away) and make your crosses. If you like, just cut crosses in the tops.

Put the tray in a cold oven, and set it to 200⁰C and bake for 20 to 25 minutes (you get a better rise if they go into a cold/just warm oven, if you have to put them into a hot over, knock 5 minutes from the cooking time).

When they are almost ready, make the glaze: boil the sugar and water to a syrup and when the buns come out of the oven, brush them with the glaze twice.

Eat, warm or cold with butter. To reheat them, bake in the oven for 10 minutes at 150⁰C.