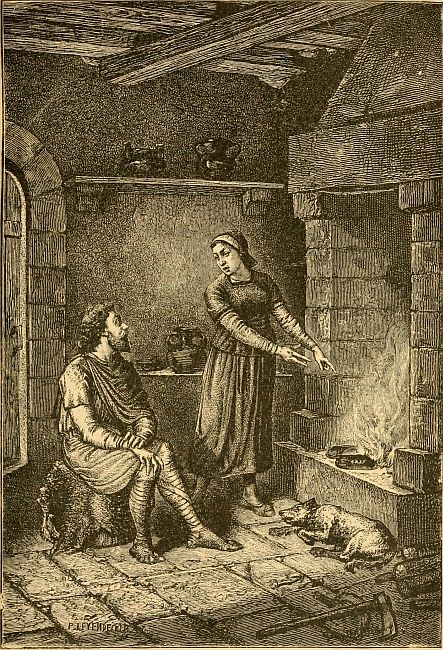

Hello there folks, just a quick post relating to my previous one about Alfred the Great burning the cakes. As I was researching it, I came across a fungus I had not heard of before called King Alfred’s cakes. Regular readers will know that I like to go on a good forage and that I like to post about the food I find out and about.

The King Alfred’s cakes fungus, although I had not heard of it, is very recognisable to me because it is very common across the United Kingdom any time of year.

The King Alfred’s cakes fungus (English Country Garden)

The black spherically-shaped fruiting bodies are not edible, but they do look a lot like burnt balls of dough, I’ve seen them all over the place, but never bothered looking them up in a fungi field guide because you can see that they are inedible.

However, it seems that there’s an epilogue to the fable: King Alfred, so mortified was he that he’d burnt the housewife’s bread cakes, he scattered the fungal cakes to hide his mistake and embarrassment.

The fungus sprouts almost exclusively from dead elm trees and fallen branches, so keep an eye out in woods, as the chance that this fungus is present is very high, looking remarkably like small round charcoal briquettes. It doesn’t rot away quickly like most other fungi, but it sits on the dead wood getting darker and more coal-like with age.

I’m not just posting about King Alfred’s cakes because of the link to the story, but also because they did (and do) have a use in the kitchen or fireside. The fungus’s fruiting bodies, when dry and brittle catch fire easily, but smoulder at a very slow rate, and as long as they are getting plenty of oxygen, one can use them to transplant fire from one location to another. Indeed, if enough are collected, they make excellent fuel in their own right. It is for this reason that the fungus is also called coal fungus.

A smouldering fruiting body (Serious Outdoor Skills)

How ironic would it be if the herdsman’s wife had used the King Alfred cake fungus to light or fuel her fire that King Alfred went to burn the cakes on!?

King Alfred’s cakes also go by the name of cramp balls, due to an old odd belief that carrying the fruiting bodies in your pocket alleviates cramp.

Natural History

The scientific name for this type of fungus is Daldinia concentrica, so-called because of the dark and light concentric growth rings you can see if you crack one open. Fruiting bodies are usually between 1 and 5 cm in diameter but can sometimes grow much larger. Daldinia is found in deciduous woodland and is almost entirely present on the dead wood of ash trees, and since the ash is our third most common tree, the chances are you’ll have some of the fungus growing in woods near you. (Not sure what an ash tree looks like? No worries just click here for an excellent description). Old fruiting bodies are black, but when they first emerge, they are red-brown colour, only blackening when mature.

Concentric light-dark growth rings (Ian Hayhurst)

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.