Welcome to the second of a two-part podcast special all about Burns Night.

Burns Night, celebrated on Robert Burns’ birthday, 25th January, is a worldwide phenomenon and I wanted to make a couple of episodes focussing upon the night, the haggis, but also the other foods links regarding Scotland’s national poet, Robert Burns.

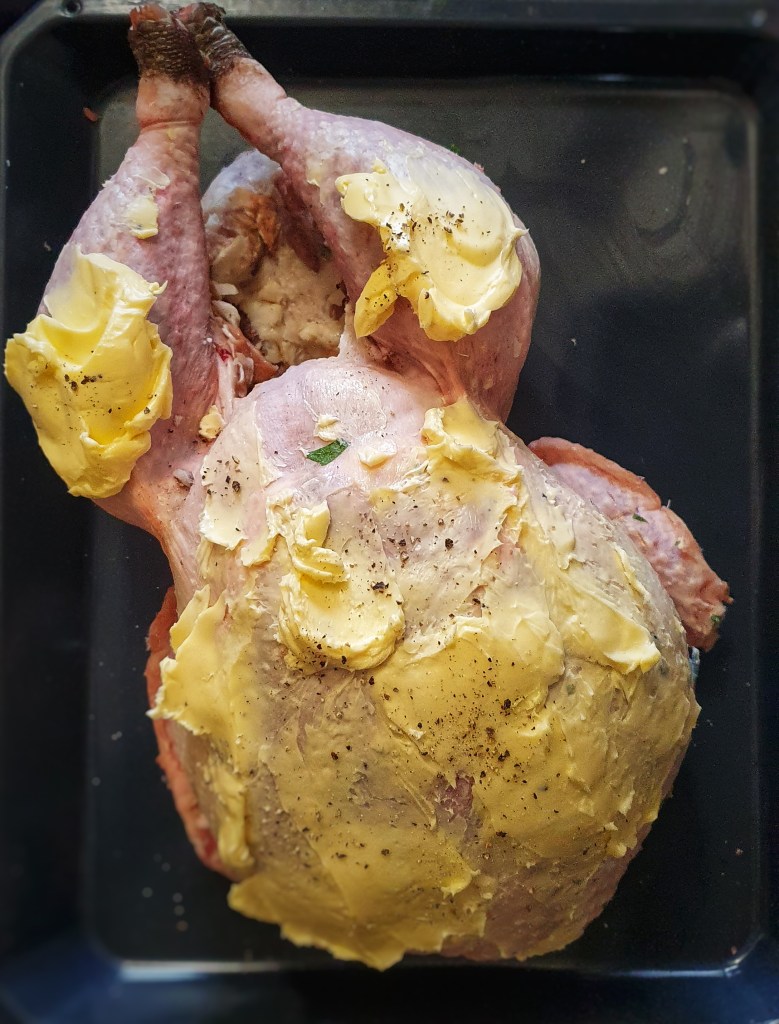

So, if you’re readying yourself for a Burns supper, I hope this episode gets you even more into the celebratory spirit. If you’re not marking Burns Night? Well, hopefully after listening to this, you will be inspired to get yourself some haggis, neeps, tatties and a dram of whisky.

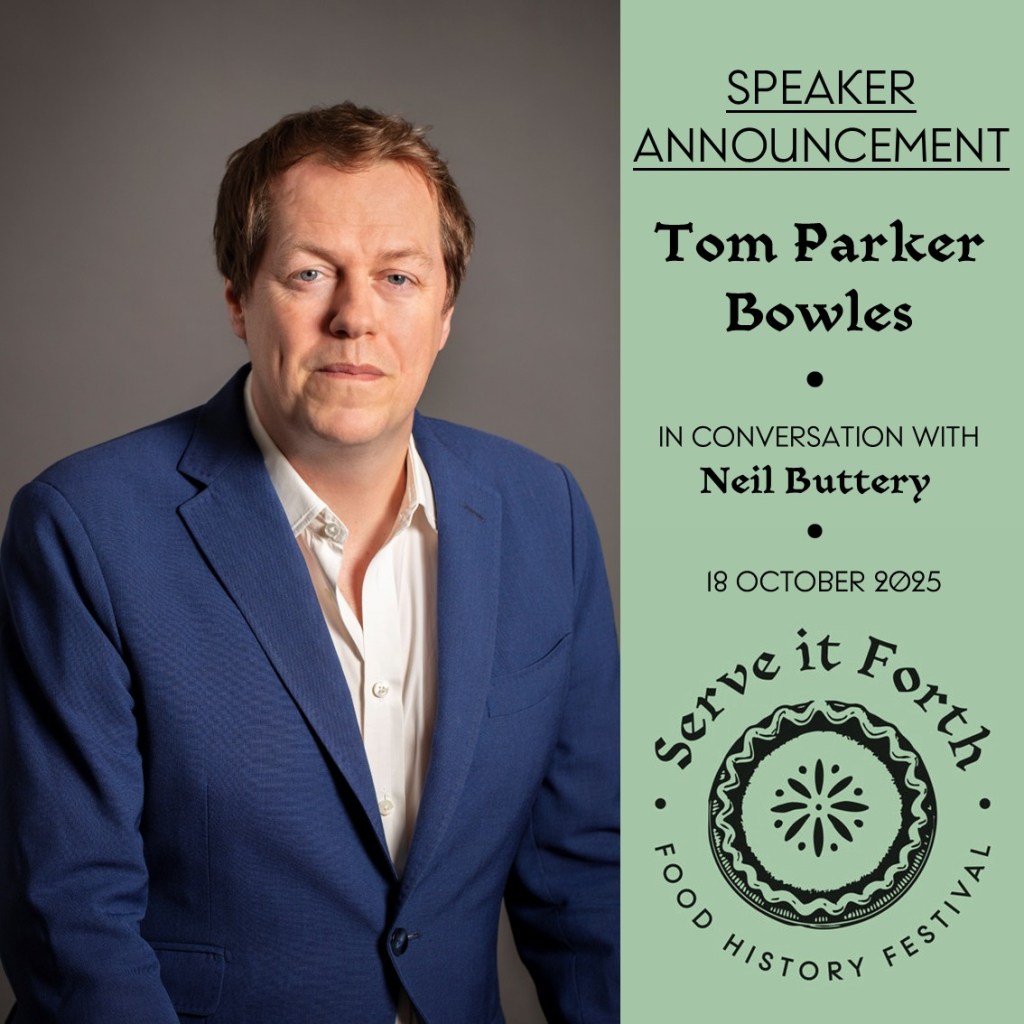

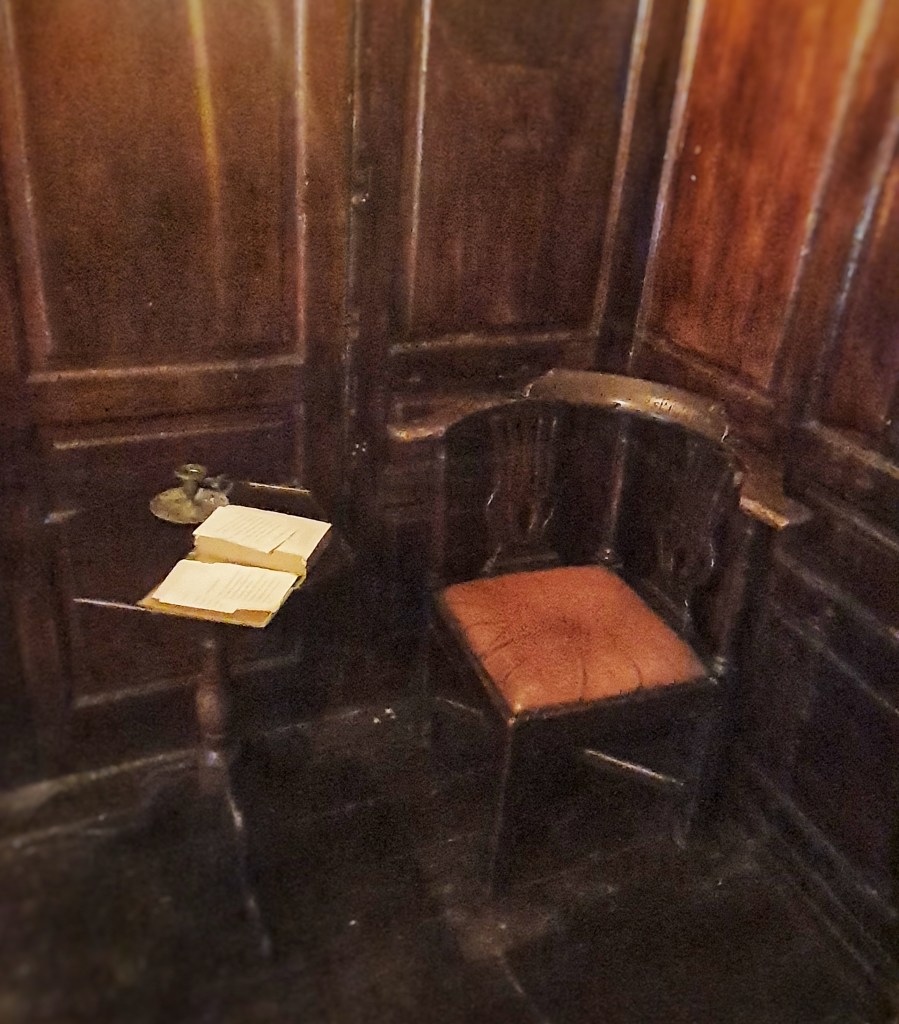

Today’s episode is a jam-packed one where I speak with three guests all about Robert Burns and his links with Dumfriesshire, Southwest Scotland. First of all, I speak with Jane Brown, Honorary President of the Robert Burns World Federation, and ex-manager of The Globe, Robert Burns’s favourite haunt when he lived in Dumfries during the last eight years of his life. Jane has attended and spoken at many Burns Nights all over the world, so there’s no one better to talk about with Burns’s life, which had several links with food and drink: there’s Burns Night and the Address to a Haggis, his time as an exciseman and as a farmer, and his time at the Globe. Then there’s the Globe itself and all of the precious artefacts contained within it that have been painstakingly conserved by owners Teresa Church and David Thomson.

The British Food History Podcast is available on all podcast apps and now YouTube. You can also stream it via this Spotify embed below:

David and Teresa also own the Annandale Distillery, which produces a delicious and unique single malt whisky. It’s available unpeated and called Man O’Words, after Robert Burns, and the other is peated and called Man O’Sword, after the other local historical figure associated with Dumfries, Robert the Bruce. Like the Globe, the old distillery was saved, beautifully conserved and brought back to life by David and Teresa.

In today’s episode, we talk about Burns’s before and after graces, Burns’s penchant for scratching poetry on inn windows, the importance of cask size on the flavour of whisky, and just what exactly possessed David and Teresa to buy the Globe and a falling-down distillery in the first place – amongst many other things.

Don’t forget, there will be postbag episodes in the future, so if you have any questions or queries about today’s episode, or indeed any episode, or have a question about the history of British food, please email me at neil@britishfoodhistory.com, or leave a comment below.

The Robert Burns World Federation

Follow 1610 at the Globe on social media: Instagram @theglobeinn1610; Facebook https://www.facebook.com/theglobeinn/?locale=en_GB; X @The GlobeInn1610

Follow Annandale Distillery on social media: Instagram: @annandale_distillery; Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/annandaledistillery/?locale=en_GB; X: @AnnandaleDstlry

If you can, support the podcast and blogs by becoming a £3 monthly subscriber, and unlock lots of premium content, including bonus blog posts and recipes, access to the Easter eggs and the secret podcast, or treat me to a one-off virtual pint or coffee: click here.

This episode was mixed and engineered by Thomas Ntinas of the Delicious Legacy podcast.

Things mentioned in today’s episode

Article: Local whisky maker hailed for its ‘world class’ and ‘immaculate’ malt at top awards. From in-Cumbria

Annandale Distillery on Visit Scotland website

MMR website (David and Teresa’s day job!)

David’s article about the importance of cask size when maturing whisky

My ‘Taste of Britain’ series in Countrylife Magazine

Previous pertinent blog posts

Previous pertinent podcast episodes

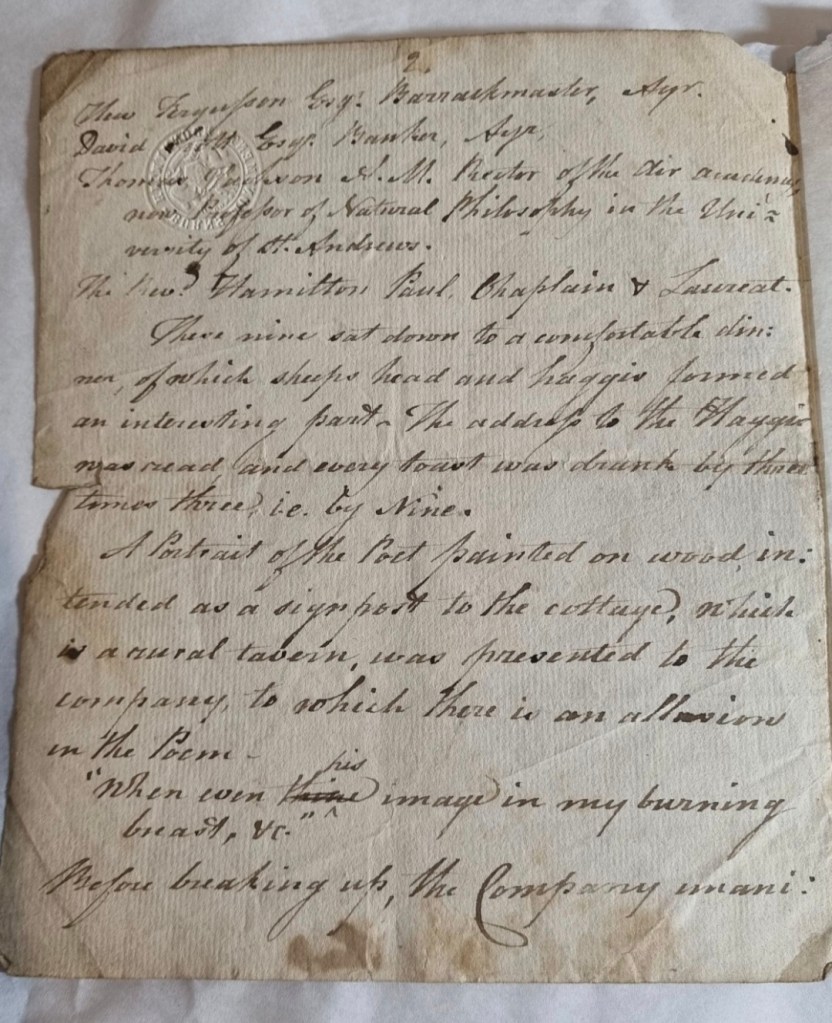

Haggis and the First Burns Suppers with Jennie Hood

Neil’s blogs and YouTube channel

The British Food History Channel

Neil’s books

Before Mrs Beeton: Elizabeth Raffald, England’s Most Influential Housekeeper