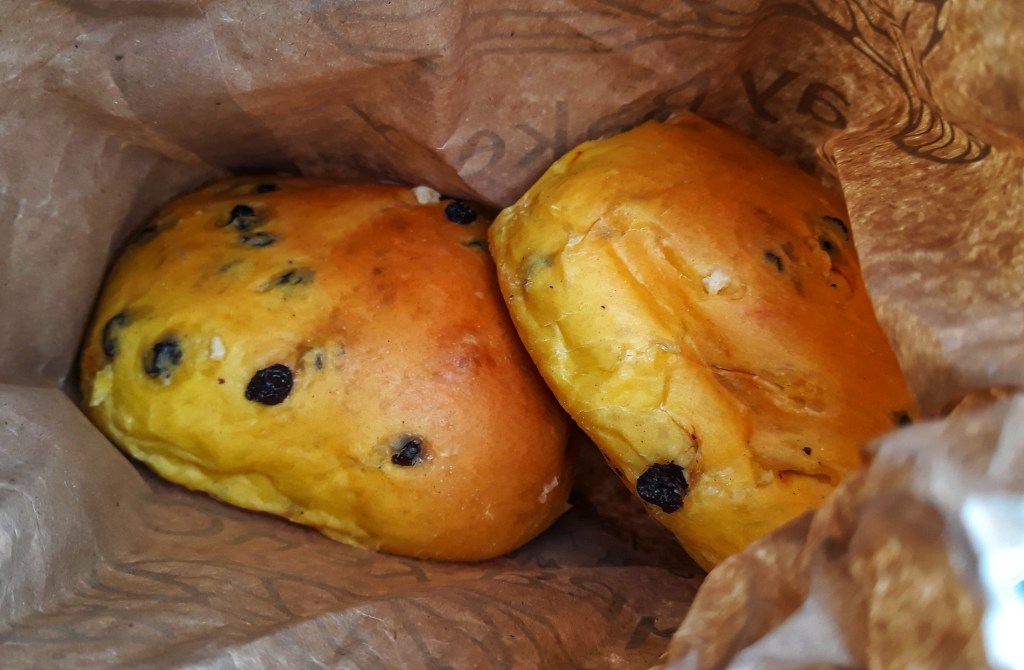

As promised, some Cornish recipes and I start with a classic. Cornish pasties are a simple combination of chopped (not minced) beef, potatoes, turnips and onions. It’s seasoned well – especially with black pepper and baked in shortcrust pastry. You can moisten it with a bit beef stock and season it further with some thyme leaves if there’s some hanging around, but you really don’t need to. Sometimes you may find some carrot in your pasty, if you do, thrown it back the face of the person who gave you it, because there is no place for carrot a Cornish pasty.

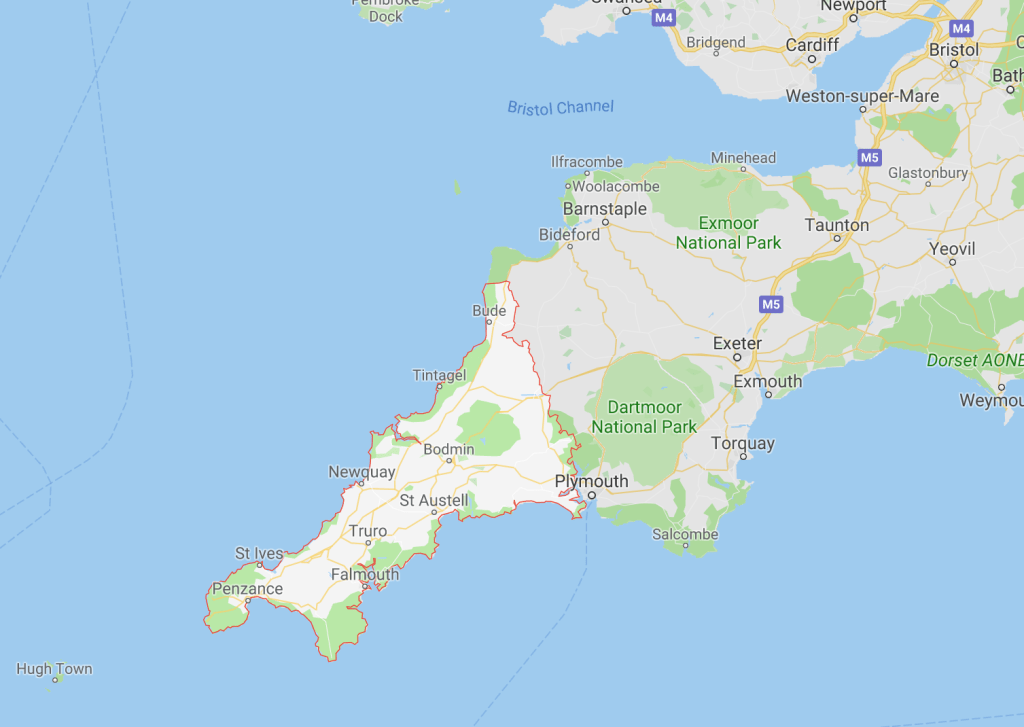

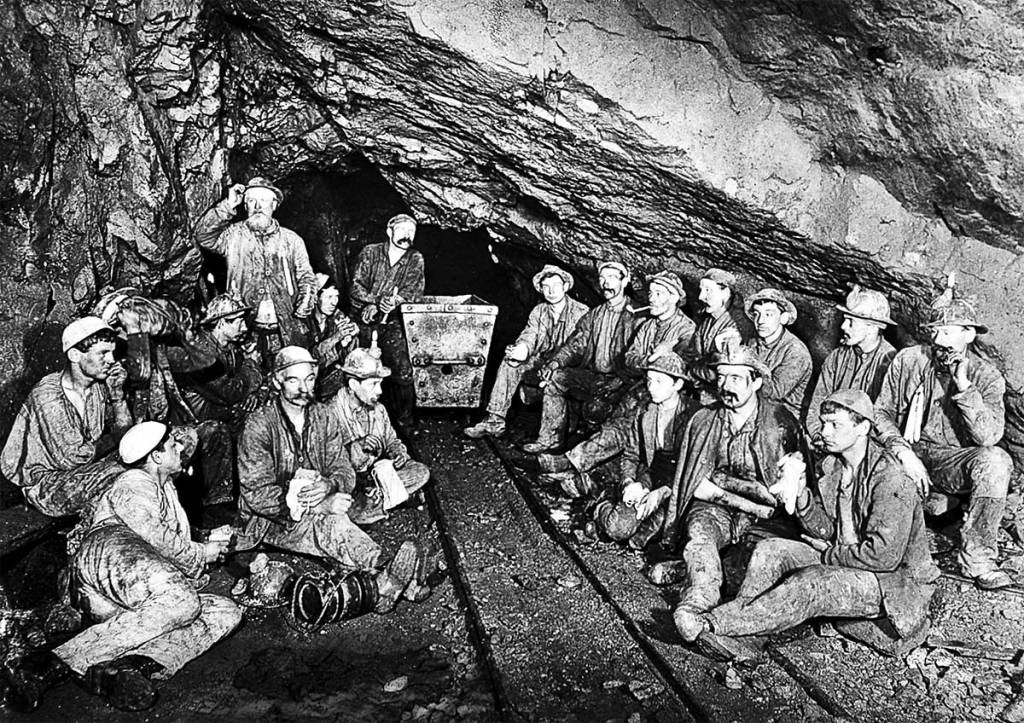

Cornish pasties were given to Cornish tin miners or field-workers so they could slip one into their pockets and eat them for lunch, the thick crimp being a useful handle protecting it from dirty fingers. The meat-to-vegetable ratio varied depending upon what folk could afford at the time. It don’t think it should be too meaty, but if you disagree simply alter my proportions in the recipe below.

Also, for a Cornish pasty the crimp must go down the side, not over the top, as you might see in some bakeries. That is a Devonshire pasty, I believe.

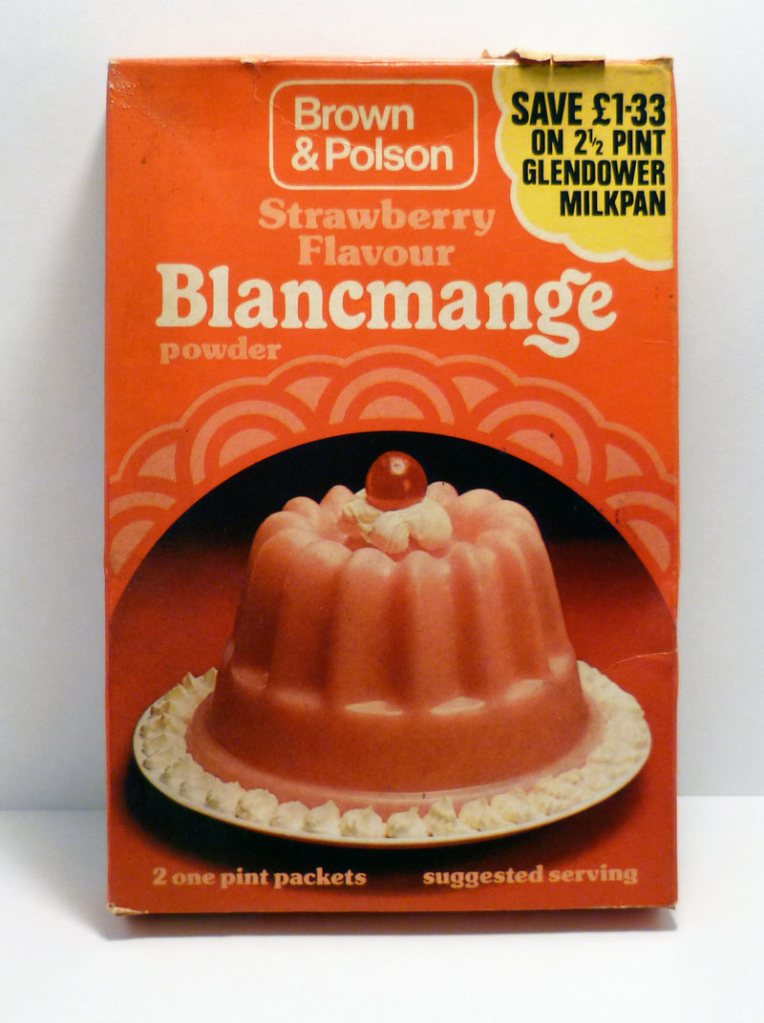

As discussed in the comments in my previous post, these pasties did not have a sweet filling at one end and a savoury one at the other. What you have there is Bedfordshire clanger, but I’m sure you knew that.

One final thing, some advice from Jane Grigson: “Cornish pasties are pronounced with a long a”. We use a short a Up North, and I refuse to change.

If you’ve never made a pasty in your life, this is the one to start with; the ingredients are raw so there is no messy gravy and juices getting everywhere and making things difficult. It seems too simple to be delicious, but it is. The secret is in the seasoning. I use a rounded teaspoon of salt, but you can use less; be warned though, use no or little salt, and you will have a bland stodge-fest before you, my friend.

On the subject of salt, notice the crazy amount of salt in the egg wash – a good half-teaspoon of salt in your beaten egg provides a strong and appetising shine to the final product. I believe that is, as the kids say, a kitchen hack.

For 2 large or 4 medium-sized pasties:

For the shortcrust pastry:

400g plain flour

100g each salted butter and lard, diced

around 80g water

For the filling:

300g chuck, skirt or braising steak, gristle and fat removed

125g onion (a medium-sized one), chopped

125g turnip, peeled and thinly sliced

250g potato, peeled and thinly sliced

salt and freshy-ground black pepper

thyme, fresh or dried (optional)

4 tbs beef stock or water

Egg wash:

1 egg beaten with ½ tsp salt

Begin with the pastry. Place the flour, butter and lard in a mixing bowl. If you have an electric mixer, use the flat beater and turn on to a low speed until the mixture resembles breadcrumbs. If you are doing this by hand, rub the fat into the flour with the tips of fingers. It shouldn’t take longer than five minutes.

Trickle in the water with the mixer on its slowest speed and stop it as soon as the dough comes together. If doing by hand, add half the water and mix in with one hand, trickling in the rest of the water as you mix.

Either way the dough should some together and not feel sticky – it shouldn’t stick to your worktop, but it will feel a little tacky.

Lightly flour your work surface and knead the pastry briefly. This is where you may go wrong – over-kneading results in tough, shrinking pastry. The way to tell you are done kneading is to pinch some of the dough between your thumb and forefinger – it should just split around the edges when you pinch it hard (see pic).

Cover the dough and pop in the fridge to rest for 30 minutes.*

Meanwhile, get the filling ready. Place all the vegetables and a good pinch of thyme if using in a large mixing bowl. Season and mix with your hand, then add the meat, season that and then mix in. Remember to be generous with the black pepper – add what you think is sufficient, then do a couple more twists of the milk.

Remove the pastry from the fridge and split into two or four equal pieces. Form into balls and roll each out on a lightly floured surface, using a lightly floured rolling pin. I rolled out two large dinner plate sized circles of dough to around 3mm thickness – that of a pound coin. Don’t worry if they are a little wonky, they get tidied up as we go. That said, if it’s looking more like a map of the Isle of Wight than a circle, you might want to neaten up a little.

Now heap up the filling in a line just slightly off centre, dividing equally between the circles of dough. Sprinkle with the beef stock or water. Brush a semi-circle of egg wash down the edge nearest to the filling and then fold the dough over leaving the dough beneath poking out by 5 or 10mm.

Next egg wash the side again and crimp down the edge – this makes things extra-secure as the filling expands in the oven. To crimp, fold over one corner inwards with a finger, squidge down the next section of pastry and repeat until you have worked all your way around the pasty.

Place on a lined baking tray, egg wash the tops and poke in a couple of holes with a sharp knife. Bake for 1 hour at 200°C, turning down the temperature to 180°C once the pastry is golden brown, around 20-30 minutes into the bake.

Remove and eat hot or cold.

*I will write a more in-depth method for pastry at some point, honest!

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.