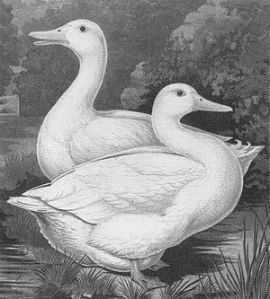

Mary Simmons of Hartwell’s prize-winning Aylesbury ducks

Long before the chicken became the country’s favourite fowl for the dinner table, there was the duck. The Chinese domesticated it 4000 years ago and it is still their meat of choice. The Egyptians were not too far behind the Chinese; they captured eggs that were hanging about in nests amongst the reeds on the banks of the Nile. The duck truely is the “veteran of the henhouse”. Britain too did love its roast duck, though duck breeding did suffer greatly during the World Wars and never really recovered.

All farmed ducks today are all descended from the seemingly ubiquitous mallard. Farmed ducks and mallards differ greatly in size: farmed ducks are commonly double the size of their wild cousins and are often seen capturing and eating whole frogs in a single bite! Prior to domestication, many of the duck species that were caught and eaten were migratory, coming and going like clockwork as the seasons passed. Heavy symbolism was therefore attached to the eating of them, and they were integrated into feasts. They are still eaten in Romania at the vernal equinox.

In Britain, the most well-known duck breeds are the Aylesbury and Gressingham, though they are by no means the most common. Many breeds dwindled in number so much that they went extinct, though some have been saved, such as the Silver Appleyard. The most common ducks that are reared for the table these days are the Pekin and Barbary ducks; the latter of the two must be rather stealthy as it is very common to see escapees hanging around ponds in Britain (and indeed the USA).

The Aylesbury Duck

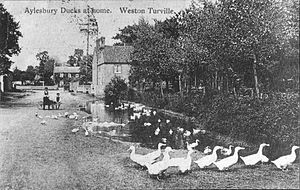

When people think of British ducks, they think of the Aylesbury – with their gleaming white plumage, orange legs and feet and sturdy bill set high upon their skull. Even if one did not know of the Aylesbury duck, I am sure that this is the picture one would have in their head. Beatrix Potter’s Jemima Puddle-Duck was an Aylesbury for example (though she lived up North). Aylesbury ducks were not originally bred for their meat at all, but for their quills. In the nineteenth century, however, the switch was made. The reason being the folk of Aylesbury saw an opportunity to feed the ever-growing London population. Selling was successful – it must have been quite a sight to see the drovers walking the ducks from Aylesbury to London every week to be sold at market.

This seems all very picturesque, but in reality it was far from it. The ‘Duck End’ area of Aylesbury, where the ducks were bred was unsanitary, ducks were not kept in farms but were allowed to roam free, and taken into people’s homes at nighttime. However, Aylesbury’s attraction endured and conditions were better by the twentieth century. Then came The Great War, which damaged duck farming greatly and World War Two almost wiped it out completely. By the 1950s, there was just one significant flock of Aylesburys left and by 1966 there was no more breeding of Aylesbury ducks. Birds were often sold under the name Aylesbury, but they did not ‘contain a single Aylesbury gene’.

It is not all bad news though: some individuals did remain, though most had cross-bred with mallards. However, there was a large effort to bring back the breed and so the small mongrel population was selectively bred and we now have Aylesbury ducks once more.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

Duck Dishes

Ducks are no longer commonly eaten and are certainly considered a treat, save for special occasions. The most common way to eat them these days is by roasting them, though you can buy the breasts quite easily now, but for a large price – they are sometimes more expensive than the whole bird. Ducks were commonly simmered with herbs and vegetables, preserved in curative brines and, most bizarrely, sent through a press to make the infamously opulent dish duck in blood sauce. Anyway, below is a list of British duck dishes, some of which are rather old or obscure. I intend to tell you all about each one in separate posts, and hopefully I’ll be cooking most and providing recipes. I have also included some recipes outside of Britain that I think have influenced our cuisine in some way. Some I have already tackled as part of my other blog. Any that I have written up as a post will have a lovely link to send you straight to it. If there are any omissions, or you have your own recipe, let me know and I shall add them to the list. Here goes:

- Roast Duck

- Delia Smith’s duck with Morello cherries

- Duck with mint

- Stewed duck

- Duck stewed with green peas

- Duck terrine

- Fois gras

- Isle of Mann salt duck

- Duck baked in a salt crust

- Duck in blood sauce

- Confit of Duck

- Duck á l’orange

- Duck á la braise

- Duck á la mode