from iggandfriends.wordpress.com

Hot buttered toast must be the most popular British breakfast item, whether eaten on the run to the bus stop, or served up with a full English breakfast or posh scrambled eggs and smoked salmon on a Sunday. Elizabeth David described it as a ‘peculiarly English…delicacy’.

It is true that the wafting smell of freshly made toast combined with the sight of the slow melting of a good covering of salted butter is so comforting. Indeed, the first thing offered up to you after you’ve come round from an operation on the NHS (and I unfortunately have had many times) is tea and toast. (Digressing slightly, the first thing offered up to you after an operation in the USA is the similarly comforting cookies and milk.)

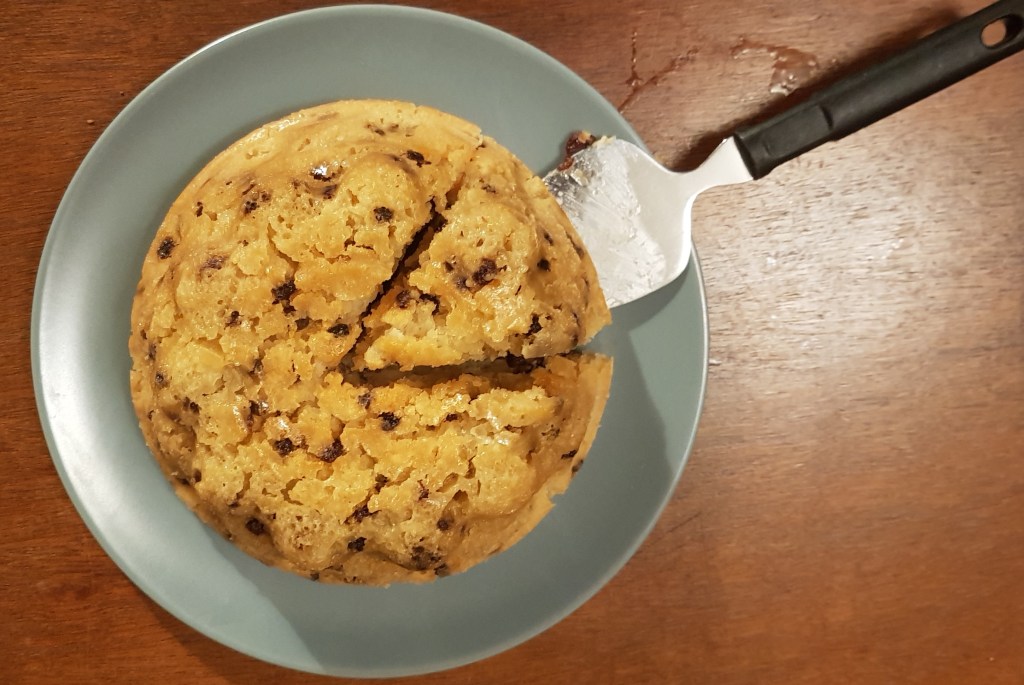

Most toast today is, of course, made from the flabby Chorleywood processed white sliced loaf, which produces quite depressingly poor ‘wangy’ toast. Proper toast requires proper bread; bread that has gone a slightly stale. Perfect toast is in the eye of the beholder: thick, thin, crisp throughout, soft in the centre, pale, dark, a scraping of butter or lashings of it.

Making toast was a way of using up stale bread, of course, so toast shouldn’t even be required now that we have the invention of Chorleywood processed bread. It’s ironic that our love of toast means we, on the whole, now make it with a product unsuitable for making it.

It won’t surprise you that there are some very detailed descriptions in old cookbooks as to the best way for making toast.

The earliest official piece of toasting equipment was the toasting fork. Here’s the flamboyant Victorian chef Alexis Soyer’s instructions from A Shilling Cookery for the People from 1854:

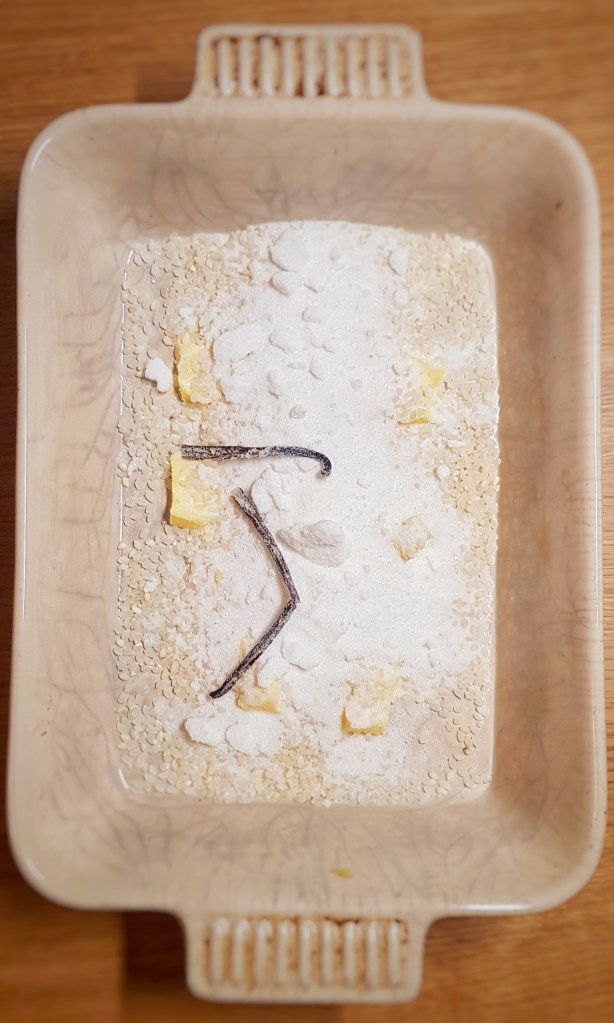

How to Toast Bread – Procure a nice square loaf that had been baked one or two days previously, then with a sharp knife cut off the bottom crust evenly, and then as many sliced you require, about a quarter of an inch in thickness. Contrive to have a clear fire: place a slice of the bread upon a toasting-fork, about an inch from one of the sides, hold it a minute before the fire, then turn it, hold it another minute, by which time the bread will be thoroughly hot, then begin to move it gradually to and fro until the whole surface has assumed a yellowish-brown colour, then turn it again, toasting the other side in the same manner; lay it then upon a hot plate, have some fresh or salt butter (which must not be too hard, as pressing it upon the roast would make it heavy),spread a piece, rather less than an ounce, over, and cut the toast into four or six pieces. You will then have toast made to perfection.

Next rung up on the evolutionary ladder of toast-making was the invention of the toast plate, a cast iron rack that could sit in front of coal-powered range cooker. My friend Andreas actually has an original coal range cooker with a toast plate built in. I am very jealous.

You can buy plates that lay over a gas burner on the stove top that I suppose achieves a flavour closest to the ones found on the coal ranges. Elizabeth David owned one (from English Bread and Yeast Cookery, 1977):

Part of the charm of the toast produced on this device is that every piece is different, and differently marked, irregularly chequered with the marks of the grill, charred here and there, flecked with brown and gold and black.

At home, the best way to make toast is by using a grill, preferably a gas grill; it produces a much more even heat and therefore even toasting than an electric grill. I love the flecked toast that David described, but an electric grill has hot spots that produce slices well done in one patch and hardly coloured in another.

You might think all you need to do is stick the bread under the grill and wait, right? Wrong. Here are Delia Smith’s instructions for making toast under a grill, though first you need to slice it (from How to Cook: Book One, 1998):

- The key to slicing bread is to use gentle, rapid saw movements with the knife and not to push down too hard on the loaf. For toast, cut the bread into slices about ½ inch (1 cm) thickness. The crusts can be on or off, depending how you like them.

- Pre-heat the grill for at least 10 minutes before making the toast, turning it to its highest setting.

- Place the bread on the grill rack and position the tray 2 inches (5 cm) from the heat source.

- Allow the bread to toast on both sides to your own preferred degree of pale or dark golden brown.

- While that is happening, keep an eye on it and don’t wander far.

- When the toast is done, remove it immediately to a toast rack…Putting it straight on to a plate means the steam is trapped underneath, making it damp and soggy. If you don’t possess a toast rack you really ought to invest in a modest one. Failing that, stand your slices of toast up against a jar or something similar for about 1 minute before serving.

- Always eat toast as soon as possible after that, and never make it ahead of time.

- Never ever wrap it in a napkin or cover it (the cardinal sin of the catering trade), because the steam gets trapped and the toast gets soggy.

- Always use good bread, because the better the bread, the better the toast. It is also preferable if the bread is a couple of days old.

The toast rack is an essential. Before I owned one, I leant the slices against each other as you would for a house of cards.

So there we go, a definitive guide to making toast, well, as long as you’re not using an electric toaster!

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.