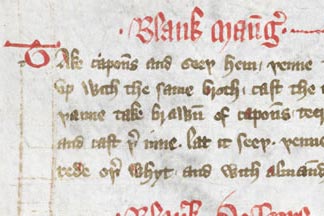

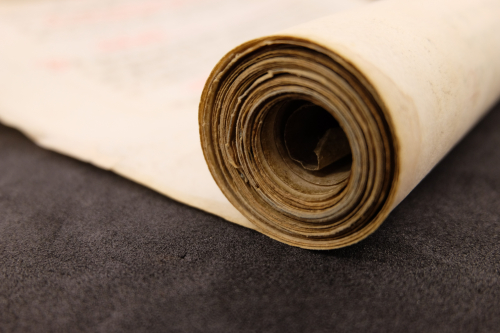

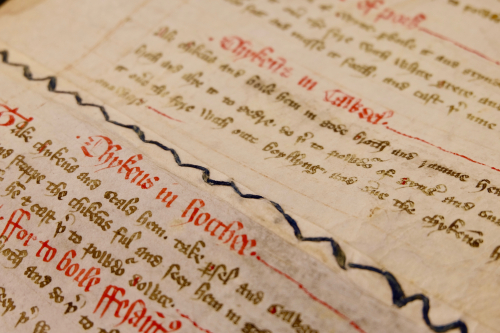

The vellum scroll rolled up (British Museum)

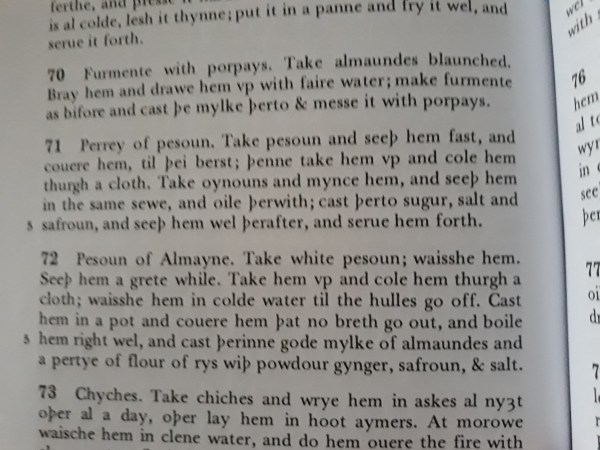

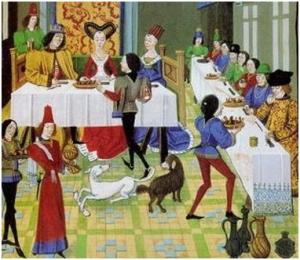

As promised in my previous post, a few recipes from the Forme of Cury. I have translated them into modern English, so you can follow them a bit easier. For the hippocras drink, I have given you my interpretation of the recipe as there are some hard-to-find ingredients. All the recipes are easy to make and taste delicious.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

Cabbage Soup

A very simple dish – not everything Richard II ate was ostentatious. This is a very simple recipe with ingredients we use today. The addition of the saffron give it an interesting earthy flavour. Powder douce was a mixture of sweet spices – the spices we would associate with desserts like apple pie – shop-bought mixed spice is good substitute. The base of the soup is broth or stock, use any you like, though I think chicken is the best for this soup.

Caboches in Potage. Take Caboches and quarter hem and seeth hem in gode broth with Oynouns yminced and the whyte of Lekes yslyt and ycorue smale. And do þerto safroun & salt, and force it with powdour douce.

Cabbage Soup. Take cabbages and quarter them and seethe (simmer) them in good broth with chopped onions and the white of leeks, slit and diced small. Add saffron and salt, and season it with powder douce.

The Forme of Cury with stitching where a new piece of parchment was added to the scroll (British museum)

If you want to know more: this blog post complements this podcast episode.

Rabbit or Kid in a Sweet and Sour Sauce

Any kind of meat can be used here really, chicken legs or diced lamb are the best substitutes. Sweet and sour sauce was called egurdouce; -douce meaning sweet and egur- meaning sour, e.g. vin-egur was sour wine, in other words vinegar! The meat is browned in lard, removed, so the onions and dried fruit can be fried, the meat is replaced with the liquid ingredients and spices and simmered just like a modern casserole or stew.

Egurdouce. Take connynges or kydde, and smyte hem on pecys rawe, and fry hem in white grece. Take raysouns of coraunce and fry hem. Take oynouns, perboile hem and hewe them small and fry them. Take rede wyne and a lytel vynegur, sugur with powdour of pepr, of ginger, of canel, salt; and cast þerto, and lat it seeþ with a gode quantite of white grece, & serue it forth.

Take young rabbits or kid and cut them into pieces and fry them in lard. Take currants and fry them. Take onions, parboil them, and chop them small and fry them. Take red wine and red wine vinegar, sugar and powdered pepper, ginger, cinnamon, salt and add them, let it simmer gently in a good quantity of lard and serve it forth.

Hippocras

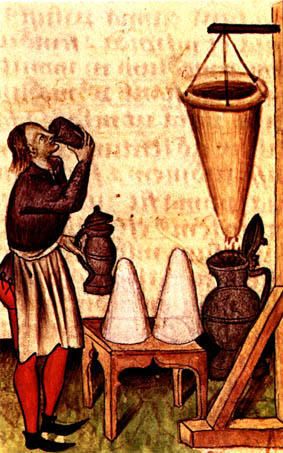

Straining hippograss through a bag

This is a really excellent recipe for spiced wine; mulled drinks were drunk throughout the year and could be served hot or cold. There are some tricky to get hold of spices, but I’ve added alternatives where appropriate. If you have to omit a spice or two, don’t worry, it will still be delicious.

Pur fait ypocras. Troys vnces de canell & iii vneces de gyngeuer; spykenard de Spayn, le pays dun denerer; garyngale, clowes gylofre, poeure long, noieȝ mugadeȝ, maȝioȝame, cardemonii, de chescun dm. vnce; de toutes soit fsait powdour &c.

To make hippocras. Three ounces of cinnamon and three ounces of ginger, spikenard of Spain, a pennysworth; galingale, cloves, long pepper, nutmeg, marjoram, cardamom, of each a quarter of an ounce; grain of paradise, flour of cinnamon, of each half an ounce; of all, powder is to be made etc.

There are a couple of tricky spices in the list: long pepper and grains of paradise are available to buy online quite easily, but are very expensive, so you can get away with regular black pepper as a substitute. Galangal is easier to find fresh than dried these days, as it is used extensively in Thai cuisine as part of their delicious red and green curries, however, seek and ye shall find the dried variety.

Spikenard of Spain is the extract of the root of a valerian plant and was used in the church as an anointing oil, it also appears very commonly in recipes. I’ve never had the opportunity to taste it.

Here’s my version of the recipe:

1 bottle of red wine

1 tsp each ground cinnamon and ground ginger

¼ tsp each ground galingale, ground black pepper, ground nutmeg, dried marjoram, ground cardamom

honey to taste

Pour the wine into a saucepan with all of the spices and bring slowly to a scalding temperature. Don’t let the wine boil as there’ll be no alcohol left in it! Let the spices steep in the hot wine for around 10 minutes.

Meanwhile spread a piece of muslin, or any other suitable cloth, over a sieve and pour the spiced wine through it into another pan or serving jug. Add honey to sweeten. Serve hot or cold.