Today is the Glorious Twelfth! The day in the countryside calendar that many await, for it is the beginning of game season.

I know it may seem a little unsavoury to look forward to the shooting of thousands of birds and mammals, but it is so woven into the tradition of country life, that it seems a rather romantic pursuit. Not one that I have been privy to of course, as it is a posh person’s game.

Technically, the 12th of August is the opening of the game season for the red grouse, though a couple of other game species can also be legally hunted from this day (see the list of game species, below).

There are two broad types of game: furred and feathered, i.e. mammals and birds. Fish are considered game too, but they do not follow the same laws as the others.

On a typical hunt for grouse and other game birds, there is a basic set up of beaters that walk in a loose line across a heath, in the case of grouse, or scrub in the case of pheasant, beating the vegetation in order to scare the birds so that they fly up and away toward gunmen to be shot. The bird is then retrieved by a gun dog such as a springer spaniel. I’m over-simplifying this, of course, but that is the basic process.

A hunter after her quarry (Lax-A)

The hunt is such a huge event and requires such a large amount of organisation, that single hunts often cost up to £50 000 per day, raking £50 million into the local economies of Scotland and Northern England each year.

How Glorious is it?

The Glorious Twelfth is controversial, with the game industry and conservationists constantly at loggerheads, but the fact is that the Moorland Association has protected many at risk species in the British Isles such as the golden plover and lapwing. They put a lot of effort into the management of heathlands by selectively burning areas and reducing the numbers of predators such as foxes and weasels. It is here that the Moorland Association has been hit with the most criticism; conservationists say they should not be culling predators so that we can have more grouse for posh men to shoot. It’s a fair point.

Then, on the really dark side are the accusations of the killing of some of our most rare birds of prey like the hen harrier.

So on one hand predator animals are often persecuted, whereas on the other, well-behaved waders are looked after.

I view the situation the same I do zoos. I know they do good work for the conservation of animals and habitats, yet I can’t help but feel sad every time I see a poor old bored elephant, or a majestic tiger walking laps around its pen. They are part of our heritage, like it or not, but they can do good work.

The Game Act, 1831

This Act of Parliament was brought in to protect game birds by bringing in closed hunting seasons, and imposed game licences (hares and deer have their own Acts, which follow similar principles). Some species were protected completely, such as the common bustard (now extinct in the UK, but there are attempts to reintroduce it).

The Game Act was brought in to replace the outdated ide of their being Royal Forests, brought in during the 11th Century during the reign of William I, where it was illegal to hunt game unless you had permission from the king. As the centuries rolled on, the laws slackened more and more until they were pretty much useless.

At the time of writing the Act, hares were not given a closed season as they were a pest. The imposing capercaillie was not included in the Act as it was extinct in the UK at the time, being reintroduced to Scotland in the 1837.

Game seasons

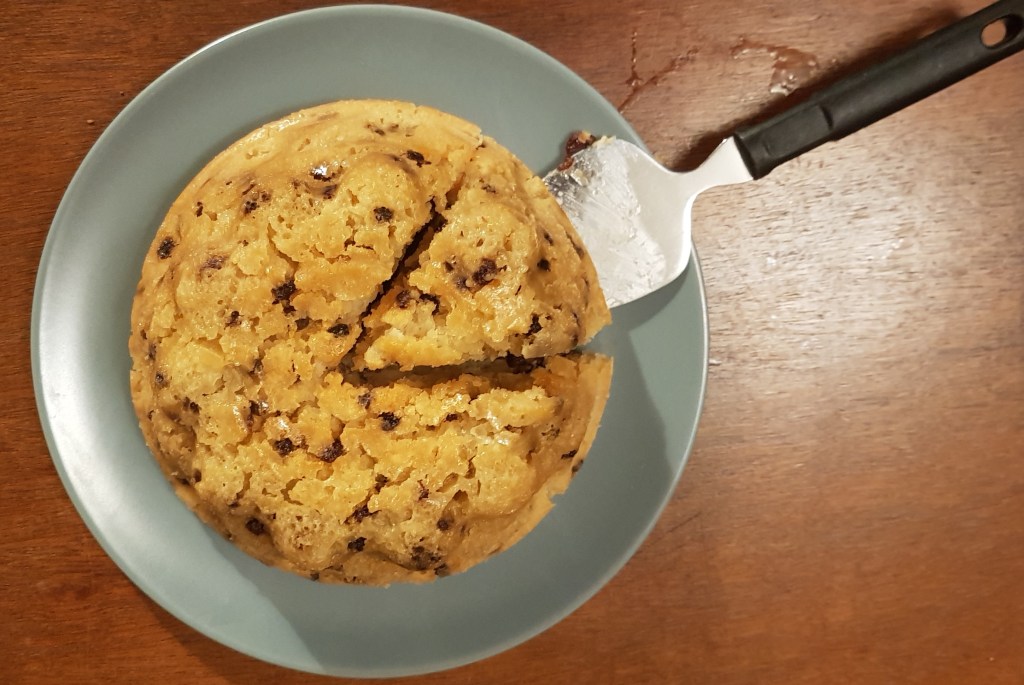

Feathered game is further subdivided into two groups: game birds and waterfowl & waders. Some of the species are familiar and other are not, and of the ones I have tried, all taste delicious (unless they’ve been hung for too long, then they are decidedly rank).

Game Birds

Red grouse, ptarmigan August 12 – December 10

Black grouse August 20 – December 10

Partridge (grey and red-legged) September 1 – February 1

Pheasant October 1 – February 1

As laid out in law, it is illegal to shoot wild birds between one hour after sunset and one hour before sunrise. In England and Wales, game cannot be killed on Sundays or Christmas Day. If the 12th of August lands on a Sunday, the season will officially begin the next day.

I have never come across a ptarmigan to buy, so if anyone knows how I can nab one, do let me know.

Game birds are often sold as a brace – a male & female. Partridges in this case

Wildfowl &Waders

Snipe August 12 – January 31

Ducks & Geese September 1 – January 31 (inland); til Feb 20 at low tide

Golden plover, coot & moorhen September 1 – January 31

Woodcock October 1 – January 31

Several species of duck and goose can be legally hunted, though many in reality, are ignored by hunters, or shot in very small numbers, such as: gadwall, goldeneye, pintail, shovelers and tufted ducks, though pintails have been spotted in my butcher’s shop before now. You are much more likely to see mallard, wigeon and teal.

Geese are a bit tricky to get hold of, unless you know someone personally that hunts, and the reason for this is that whilst geese can be shot, it is illegal to sell them. I presume this rule is an incentive to hunters to shoot the numbers they need. Legal game species are: white-fronted (England & Wales only), pink-footed, greylag and Canada geese.

A brace of mallard

The furred game can also be split into two broad groups: ground game and deer.

Ground Game

This is basically your small and furry game species:

Rabbit & brown hare January 1 – December 31

Mountain hare (Scotland only) August 1 – February 28/29

Rabbit and brown hare have no closed season, this is because at the time of the Game Act, they were both considered pests. These days, everyone considers rabbits to be a pest, but the hare does get an effective closed season from March to May, due to their fall in numbers in recent times.

Boxing brown hare (Telegraph)

Deer

There are six species of deer inhabiting the UK: red, sika, fallow, roe, Chinese water deer and muntjac. The seasons get pretty complicated here, but generally the open season runs from August to April for males (bucks & stags) and November to March for females (hinds & does). The exception being muntjac that have no closed season

Pests

There are a few pest species that can also be eaten such as rabbits, woodpigeons and grey squirrels. In the past rooks were eaten, though this is very uncommon these days.

So there you go, a whistle-stop tour of hunting in the UK. In the coming months I’ll be posting some game-related posts as I hunt around my local butchers’ shops for some delicious seasonal treats.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.