I am aiming to write at least one recipe on every cut of meat, cheap or expensive, regular or odd (see here for the main post). At Levenshulme Market a few months ago, I came across a calf’s heart at the dairy farm Wintertarn’s stall, so I bought it and stole it away in my freezer until I found a recipe I wanted to try.

Heart crops up in many recipes such as pork faggots or haggis, but these days is rarely eaten as a cut of meat in its own right. In the war-time home stuffed pig’s or lamb’s hearts were pretty popular because offal cuts were not rationed. This naturally has damaged the reputation of the heart as something that is good eating. Prior to the 20th century, heart was a very popular cut of meat, even with the middle and upper classes. I like this recipe that appears in Elizabeth Raffald’s book The Experienced English Housekeeper (1769) ‘To make a Mock Hare of a Beast’s Heart’:

Wash a large beast’s heart clean and cut off the deaf ears [see below], and stuff it with forcemeat…Lay a caul of veal…over the top to keep in the stuffing. Roast it either in a cradle spit or hanging one, it will take an hour and a half before a good fire; baste it with red wine. When roasted take the wine out of the dripping pan and skim off the fat and add a glass more of wine. When it is hot put in some lumps of redcurrant jelly and pour it in the dish. Serve it up and send in redcurrant jelly cut in slices on a saucer.

Elizabeth Raffald

I think this sounds like a delicious recipe to try, and perhaps I will when I come across a large beast’s heart in the butcher’s shop window. However, it might be a little bit of a challenge for someone not used to eating such things. Instead, I give a recipe for a delicious and simple marinated calf’s heart, as a good introduction to the texture of heart which is not as tough as old boots as you may first expect, but firm and has the familiar taste of meat. However, before you cook a heart, you need to know how to get it ready.

Preparing Heart

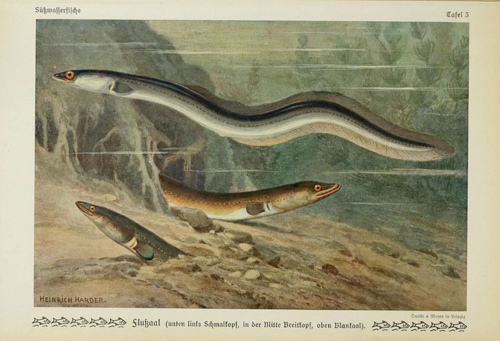

The hearts of small animals such as ducks and chickens can simply have any large blood vessels removed and you are done.

Preparing a larger heart such as calf, ox, lamb or pig might appear to be a little daunting at first, but it is really quite simple. First of all the large blood vessels as well as the two large flaps that used to be known as ‘deaf ears’ are trimmed away from the top of the heart as well as any obviously sinewy parts. This should leave the heart looking neat with two cavities within. If you want, trim away the fat, but if it is to be roasted, the fat provides a natural basting. In fact, there is so little fat within the heart itself that often it needs to be larded with strips of fatty bacon. Large ox hearts are often quartered and frozen away to be used over several meals.

Pop the heart in some salted water until you are going to cook it.

Grilled & Marinated Calf’s Heart

This recipe is a modern one and it comes from the Nose-to-Tail chef Fergus Henderson. It is very simple and very healthy – pieces of calf’s heart that have been marinated in Balsamic vinegar, quickly griddled then served up with a nice salad.

For four

Ingredients

1 calf’s heart

around 6 tbs Balsamic vinegar

salt

pepper

1 tbs chopped fresh thyme

First of all prepare the heart: trim it as explained above and remove any thicker pieces of fat. In this case, the heart is cooked quickly, so it doesn’t require the fatty basting. Cut it open and lay it out flat and cut into 2 or 3 centimetre (1 inch) squares.

You need each piece of meat to be about half a centimetre (¼ of an inch) thick, so some very thick parts, such as the ventricles, will need to be sliced horizontally. Tumble the pieces of heart into a bowl along with the vinegar, salt, pepper and thyme, making sure everything gets coated well. Cover and marinate for 24 hours.

To cook the meat, you need a red-hot griddle – either on a barbeque or over a hob – that has been lightly greased with some rapeseed oil. Place pieces of heart on the griddle and turn after 2 or 3 minutes and cook the same time on the other side.

Serve straight-away with ‘a spirited salad of your choice’, says Mr Henderson, ‘e.g. waterctress, shallot and bean, or raw leek.’

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

![20121228_191019[1]](https://fix-quick.today/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/20121228_1910191.jpg)

![20121228_184345[1]](https://fix-quick.today/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/20121228_1843451.jpg)