Well we got there. We made it into 2023 almost unscathed. I’m eating bubble and squeak, fried eggs and the remainder of last night’s steamed pudding (not all at the same time of course) and my hangover is surprisingly mild.

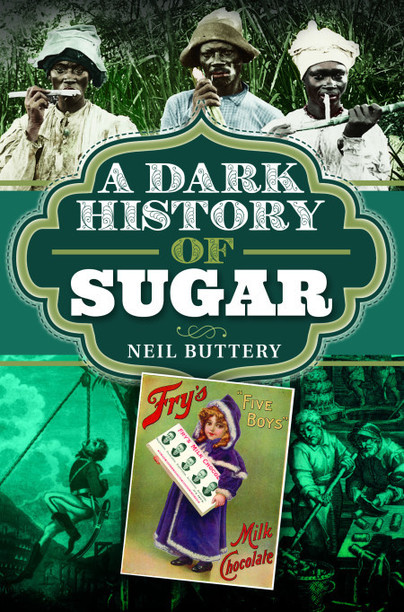

It’s been a busy year for me: the blog romps on, and the podcast has really grown wings and taken off with a rapidly-increasing listenership; and let’s not forget there was the publication of my first book A Dark History of Sugar in May of course. Not only that, but later in the year, I have my second book Before Mrs. Beeton: Elizabeth Raffald, England’s Most Influential Housekeeper will be published around Eastertime (and is available to pre-order now!).

I’m listing all of these things, not because I’m a great big fat show-off, but because none of it would have happened with you, dear reader, supporting me and following the blog and all of my other projects – something you do with fervour. I am so very appreciative, and I certainly do not take any of it for granted. So thanks for reading, thanks for listening and thanks for buying the book.

A huge thank you too to everyone who has started up a monthly subscription, and to those who have donated a virtual coffee, pint or more to help keep the blogs and podcasts going. Every year it gets more expensive just to have a podcast and blog so it really does help, and the more I receive the more time I can spend getting more online content out there for you all to enjoy.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce and would to start a £3 monthly subscription, or would like to treat me to virtual coffee or pint: follow this link for more information. Thank you.

In 2022 the blogs covered a lot of ground: there were recipes for some traditional fayre like cheese and leek pie and digestive biscuits, plus Yorkshire pudding, mutton chops and shoulder of mutton. There too was the traditional Hogmanay treat, the black bun, plus a nice eggnog to wash it all down.

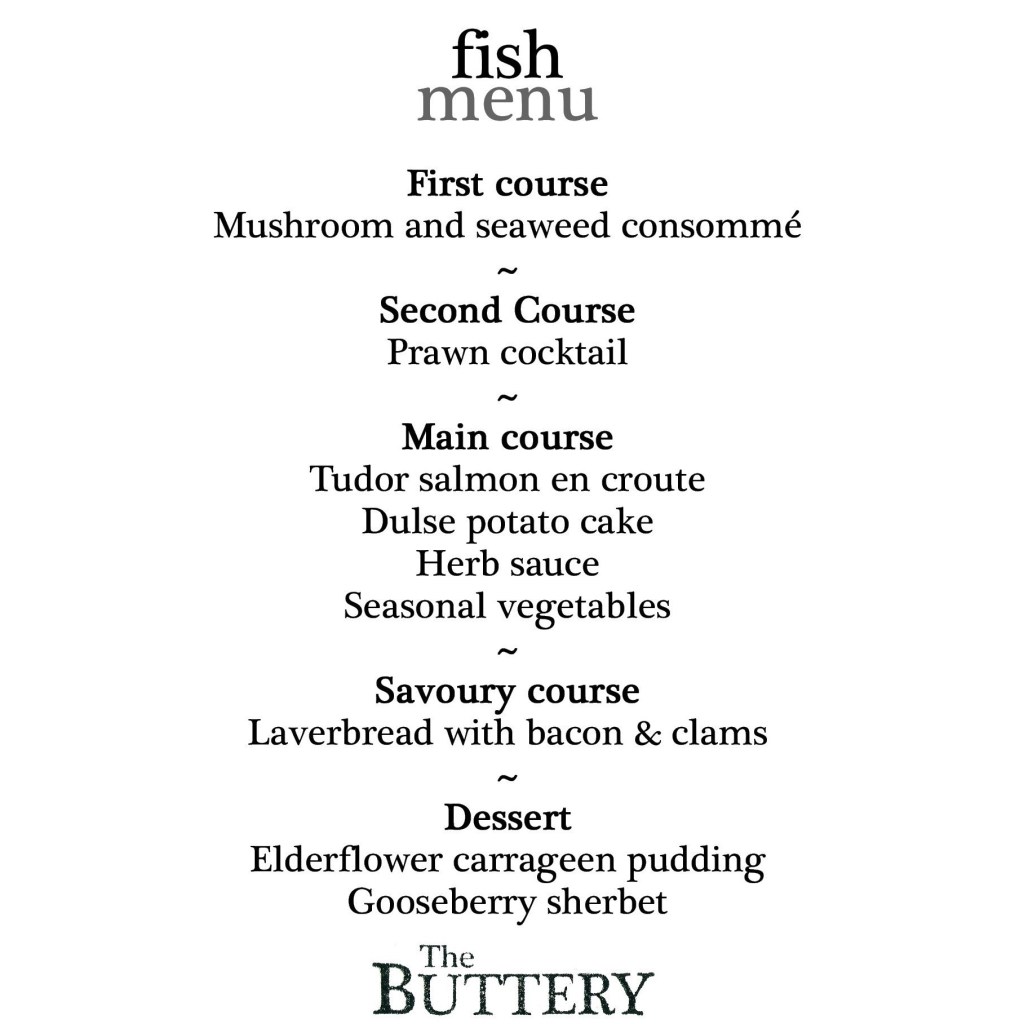

Unusual ingredients and recipes were represented too: including the surprisingly delicious colostrum pudding, a blue cheese ice cream, an Irish carrageen pudding made with elderflowers, the forgotten Scots live-fermented oat flummery sowans.

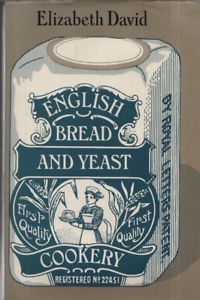

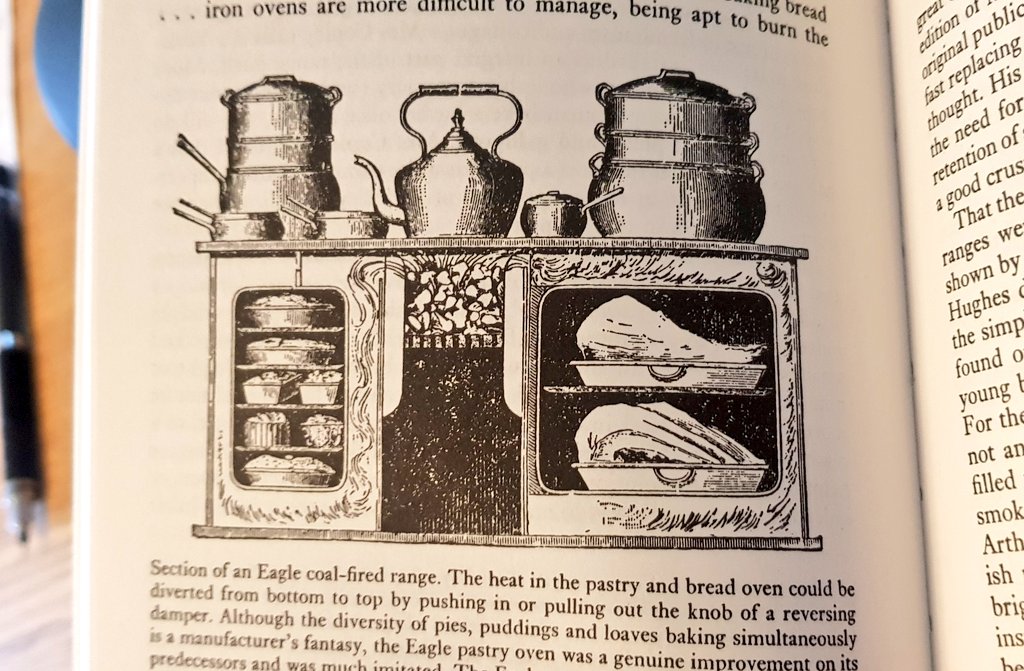

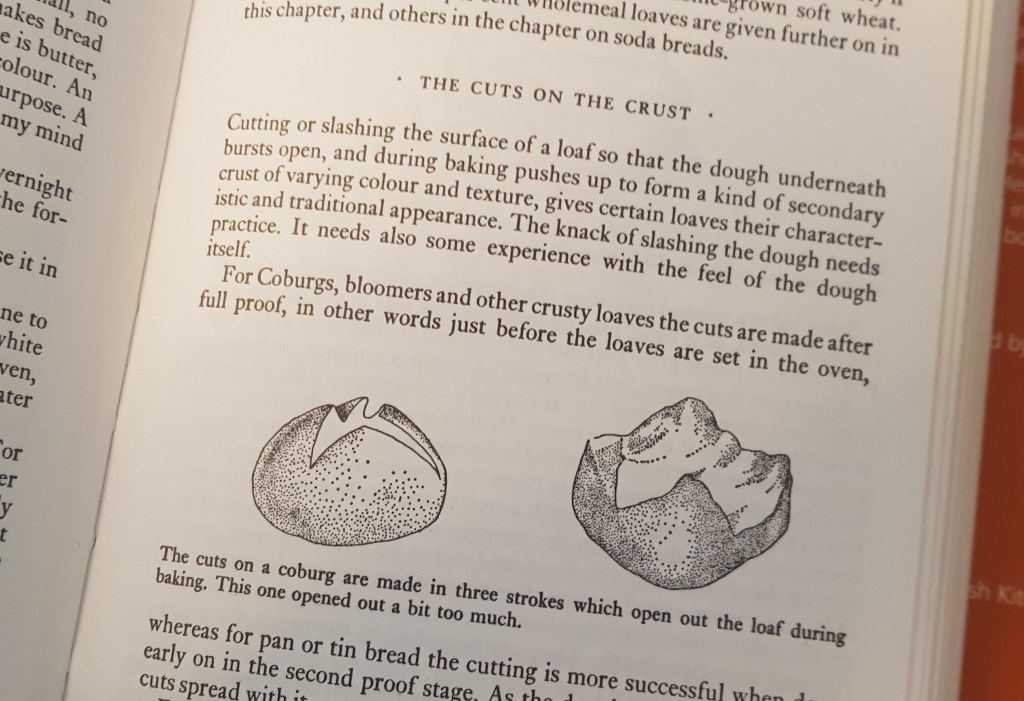

I also wrote about one of my favourite cook books: English Bread and Yeast Cookery by Elizabeth David, and used her guidance to try and recreate the early modern fancy bread called manchet, and I wrote about the Corn Laws – something we’ve possibly all heard of but don’t really know that much about.

2022 was a bumper year for The British Food History Podcast with half of season 3, the whole of season 4 and the first 2 episodes of season 5 all coming out this year – a total of 14 episodes! Topics this year have been varied: TV chef Fanny Cradock, the traditional British breakfast, herbalism, curry and Christmas feasting being just some of the topics. A huge thank you to all of my fantastic guests, newcomers and returning guests alike, who spared the time to come on: Kevin Geddes, Peter J. Atkins, Emma Kay, Felicity Cloake, Glyn Hughes, Sam Bilton, Ben Mervis, Sejal Sukhadwala, Elaine Lemm, Annie Gray and Paula McIntyre. I salute you all!

By the way, if you have any suggestions for future blog posts, recipes and podcast episodes, or have any questions or comments about any that already exist, please leave a comment at the bottom of a blog post, or email me at neil@britishfoodhistory.com.

Other highlights include a mammoth thread of cocktail recipes, and a holiday to Aix-en-Provence where I ate andouillette sausage for the first time and expected it to be delicious. I was wrong. Video evidence:

So what does 2023 hold for us? Well of course we don’t know, but I’ll be here firing off recipes, essays and podcast episodes for you all whatever happens.

Happy New Year! xxx