Regular readers of the blog will know that I have been working on a book all about sugar’s dark side over the last couple of years, and I am very pleased to announce that A Dark History of Sugar will be published on 30 April 2022 by Pen & Sword History. It is – as far as I know when I write this – available in the UK and Australia from this date. North America, you’ll have to wait a little longer for it: 30 May.

Before I tell you all about the book, I thought I’d let you know that if you pre-order via Pen & Sword’s website (so there’s not long left) you can get 25% off the cover price. The book is, of course, available from other booksellers. I will be receiving some copies, which of course will be signed by Yours Truly. I’ll let you know when they are available. I’m not sure as yet how much I’ll be able to sell them for, but hopefully it’ll be under the cover price. Keep your eyes peeled here and on my social media.

In fact there’s another reason to look at my social media: I’ll be doing some competitions on here, but also on Twitter and Instagram on, or around, publishing day. If you don’t follow me already I am @neilbuttery on Twitter and dr_neil_buttery on Instagram.

Okay, let’s talk about the book.

Writing it was very involving and sometimes even distressing and upsetting; unfortunately the history of this everyday and all-too-common commodity contains possibly the darkest in human history. But why is its history so bad? Well, it’s because it’s so good.

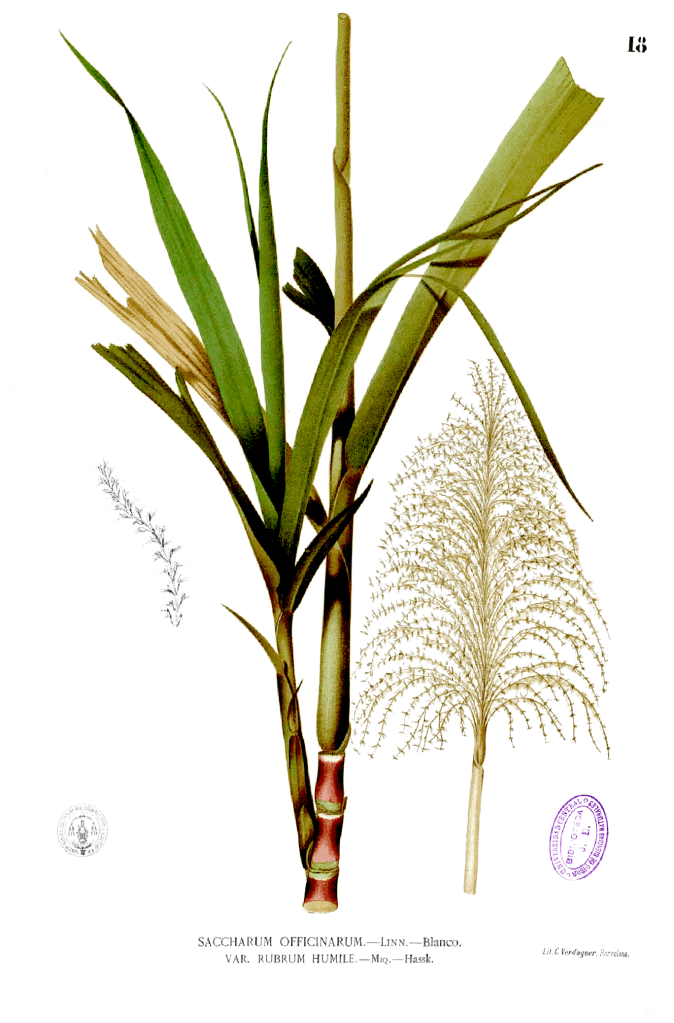

I begin the book looking at the lengths early man went to just to get its hands on honey – the purest natural source of sugar. You see, Homo sapiens adapted to spend a great deal of its time thinking about sugar and how to get hold of it. We evolved bigger brains with the ability to problem solve that feed on glucose only – no other sugar will do – and we evolved pleasure centres that are never sated and stomachs we can stuff with sweet foods well after we are full.

This evolved adaptation is advantageous if there is little sugar about, but when it’s available any time we want in any amount we want, our brains go into overdrive and out pleasure centres spin like Catherine wheels, reinforcing our behaviours, training us up to eat more and more of it. At any cost. As I say in the book:

We take sugar for granted, but now we are paying the price, and have been for some time. With cheap and plentiful sugar came centuries of exploitation, slavery, racism, diabetes, obesity, rotten teeth, and mistreatment of an exhausted planet.

But sugar and sweetness are seen as pretty favourable: sugar is good, heavenly even; little girls are made of ‘sugar and spice and all things nice’ Somebody who is described as ‘sweet’ is cute, friendly, kind, and your romantic partner is your ‘sweetheart’. We look at sugar with dewy-eyed nostalgia: baking cakes with Grandma, chocolate coins at Christmas, buying sweets in the corner shop.

The reality is different, for we are a world of sugar junkies, and as consumers we have had the wool pulled over our eyes for centuries. Of course, sugar manufacturers, confectioners and fizzy drinks companies much preferred it when we knew nothing about how sugar was made and what its effects are upon the human body.

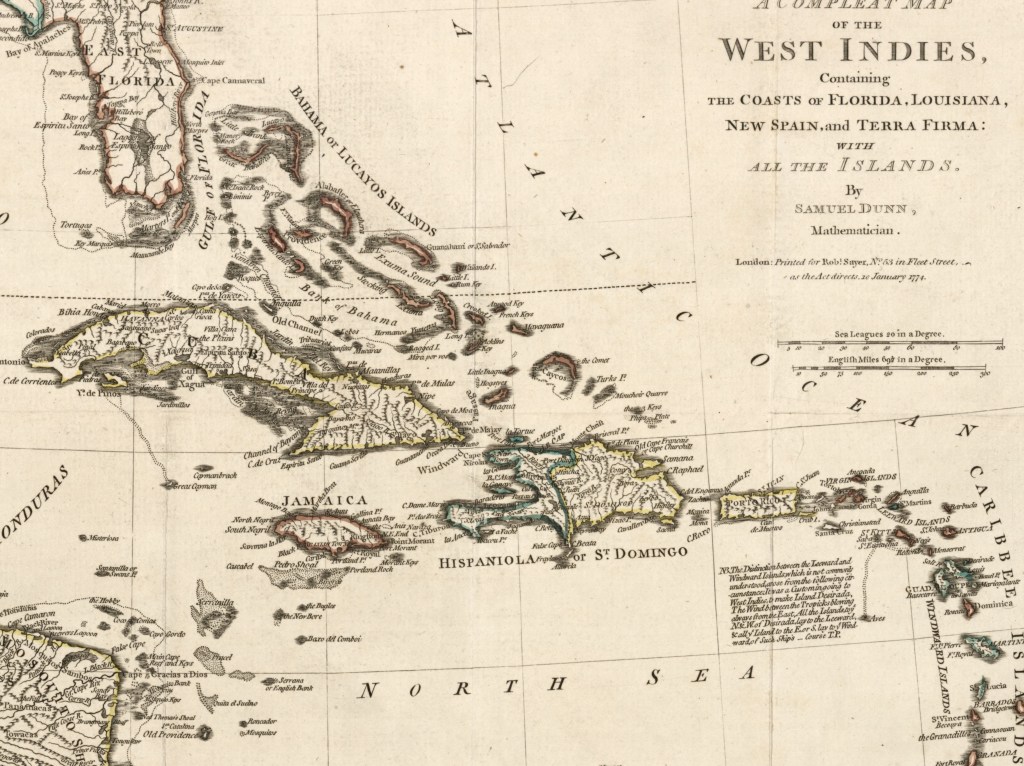

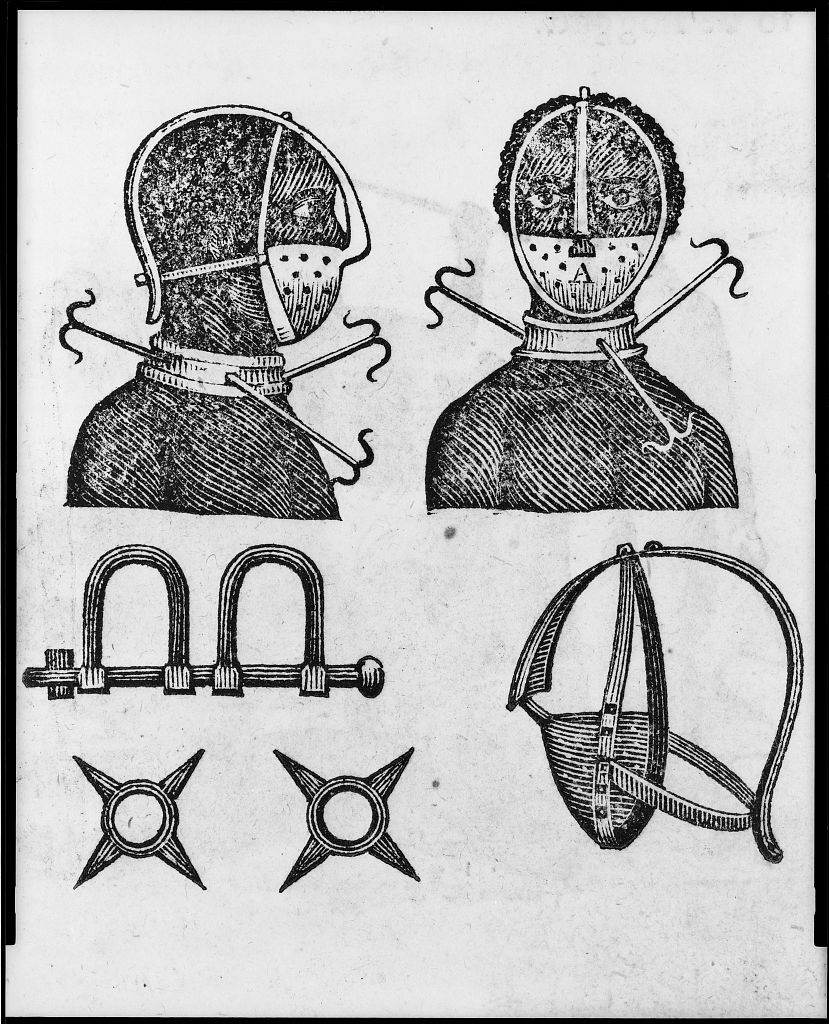

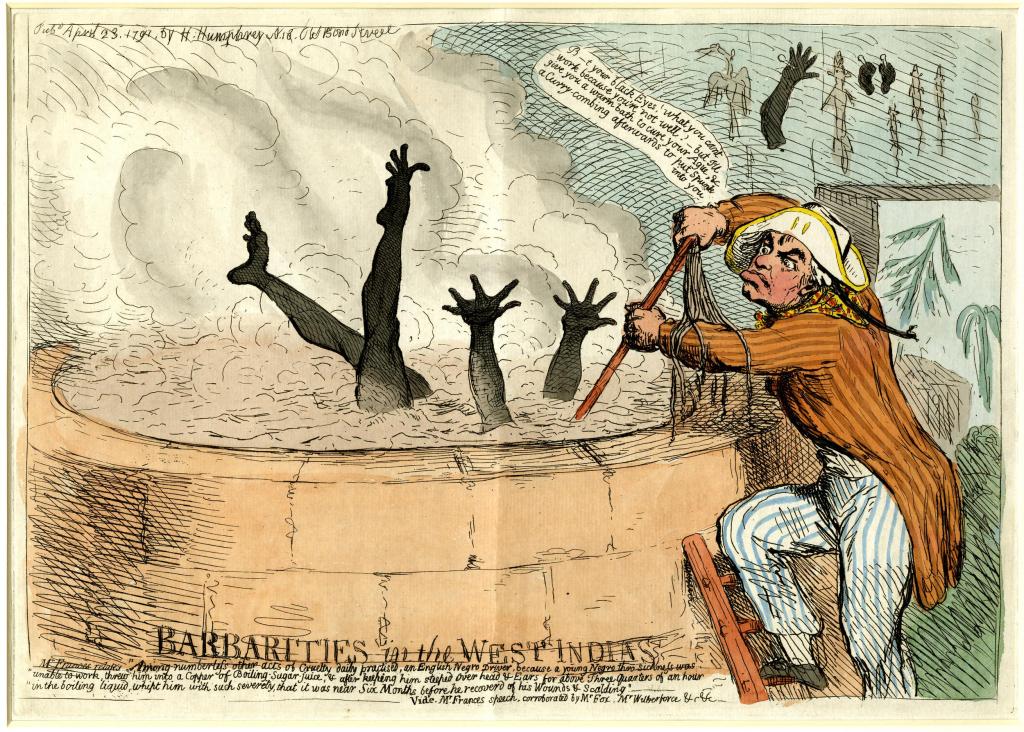

Just how did we in Europe go from returning crusading knights bringing back a few sugar samples to pass around at court, to a transatlantic trade in African slaves that displaced 12 million African men, women and children to the sugar colonies via the horrific Middle Passage?1 The slave and sugar trade made many people rich; not just investors and merchants, but also those in Britain selling fancy goods, food, tools and furniture to the colonies. This intricate web of commerce reached into almost every aspect of trade is called the ‘sugar-slave complex’.2

When the slave trade, and then slavery itself, was abolished, one might think that working conditions might have improved. Sadly they did not: new World sugar plantation owners simply swapped one type of exploitation for another, making it nigh-on impossible for freed slaves to leave them.

As the British Empire grew, so did the British sugar manufacturing industry, with sugar plantations cropping up wherever it was viable to do so. At this point, the association of sugar manufacture with exploitation could have been decoupled, but sadly this was not the case, and the indigenous people who had become suddenly, and usually violently, subjects of the empire were worked to death, and many were displaced to work on plantations thousands of miles away from home. Indian workers, for example, were forced to work on the West Indies, South Africa and Mauritius as well as India itself.

And it still goes on today: people across the world are still being exploited to make sugar, even children.

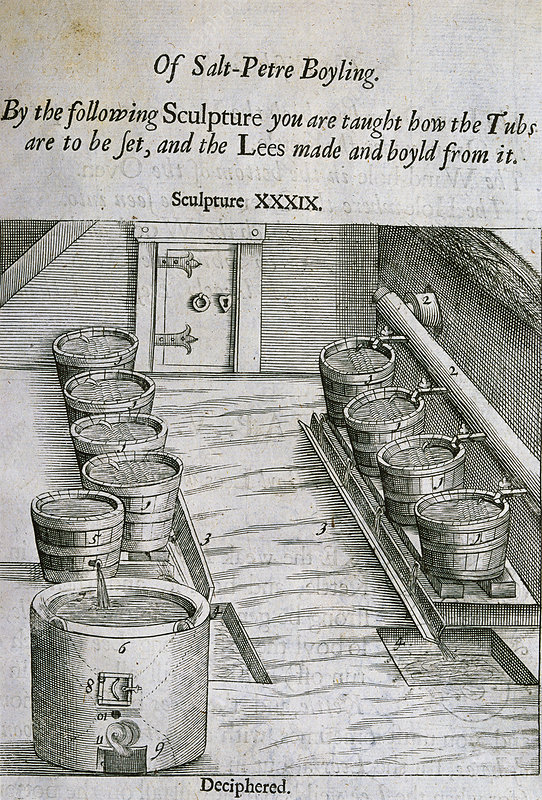

There is not enough space on the blog to go through everything discussed in the book: sugar as (useless) medicine, the Coca Cola Company, Cadbury and Queen Victoria, environmental disasters, the horrors of the sugar making processes and squalor of the slaves, rotting teeth, diabetes, Big Sugar, Christopher Columbus, the Haitian Revolution and the fact that every English monarch from Elizabeth I to George III had a stake in the sugar-slave trade. The list goes on…

I hope you find A Dark History of Sugar interesting and informative, and that I achieve my aim: to connect the dots between the first time sugar was made in Asia to the mess we are in now…and some thoughts upon how we can get out of it.

References

- Curtin, P. D. The Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census. (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1969).

- Abbot, E. Sugar: a Bittersweet History. (Penguin, 2008).