London, Parliament: Sun Through the Fog by Claude Monet 1903

London in the mid-to-late nineteenth century must have been an amazing place. There’s nothing I like more than walking around London Bridge and its environs; it is just like walking around a Dickens novel, with the romantic remains of the Marshalsea prison and roads named after his characters such as Clennam and Copperfield Street. There was however, one rather unromantic aspect to London life and that was the intense and deadly pollution created from the huge amount of coal being burnt at the time.

We talk of the smog that lie over the big cities of the modern world, Houston certainly had one, but they all pale in comparison to London smog; it had a very strong sulphurous smell and a green-brown colour to it. The Sun didn’t burn it off, but actually intensified it. Hung-out washing would be visibly dirtier once it had dried. Thousands died from heart and lung problems – it was said that a 30 second walk was the equivalent of smoking 20 cigarettes – and rickets was widespread due the lack of sunlight. A miserable place indeed:

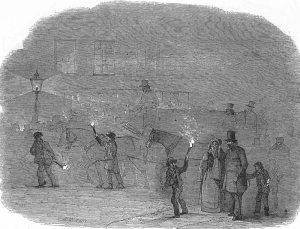

The fog was so thick that the shops in Bond Street had lights at noon. I could not see people in the street from my windows. I am tempted to ask, how the English became great with so little daylight? It seems not to come fully out until nine in the morning, and immediately after four it is gone…On the 22nd of the month, accidents occurred all over London, from a remarkable fog. Carriages ran against each other, and persons were knocked down by them at the crossings. The whole gang of thieves seemed to be let loose. After perpetrating their deeds, they eluded detection by darting into the fog. It was of an opake, dingy yellow. Torches were used as guides to carriages at mid-day, but gave scarcely any light through the fog. I went out for a few minutes. It was dismal.

Richard Rush, 1883

On several occasions, people fell in the Thames and drowned because they could not see the river right in front of them.

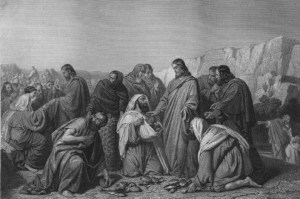

Victorian link boys guide people home

through the London smog

And so, for obvious reasons, the thick London smog became known as a ‘pea souper’. Dried pea based soups and puddings were very popular at this time, especially in the winter when there were no few fresh vegetables around. The soup became known as London particular because of a line from Charles Dickens’ novel Bleak House: “This is a London particular…A fog, miss”, said the young gentleman.

The phrase London particular had actually been around for at least a century – it was used to describe food and drink particular to London, for example London Particular Madeira.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

London Particular

This soup is really more of a potage and is very simple and cheap to make. The best thing about it is the wonderful stock made from the addition of a nice ham hock. You can use smoked or unsmoked, or you could go for a couple of pig’s trotters. Either way, it shouldn’t cost you more than 50 pence at the butcher. He might even give you them for free if you bat your eye-lashes at him. The recipe also asks for two tablespoons of Worcestershire sauce, this might seem like a lot, but it really can take it.

Ingredients

1 lb dried split peas

2 oz butter

3 rashers of smoky bacon, chopped

1 onion, sliced

1 ham knuckle, ham hock or 2 pig’s trotters

pepper

salt

2 tbs Worcestershire sauce

Have a look at the packet of peas; see if they need soaking overnight. If they are non-soak but are particularly old, you might want to soak them.

Melt the butter in a stockpot or large saucepan, add the bacon and fry on a medium heat for five minutes. Add the onion and fry until softened. Drain the peas and stir them in, making sure they get a good covering of bacon fat and butter. In amongst the peas, place the hock, knuckle or trotters and cover with water. Add some pepper, but do not add salt at this stage. Bring to a boil and skim off any grey scum, then cover and simmer gently until the peas are all mushy; around 1 ½ to 2 hours. Give the potage a stir every now and then as the peas do tend to stick, particularly towards the end of cooking.

Take out the meat joint and place to one side. Liquidise or mill the soup and return it to the pan. Pick any meat from the joints and add to the soup. Season with salt (if needed), pepper and the Worcestershire sauce.