This delicious iced dessert, which was very popular in the 19th century at Christmastime, crops up in most cookery books of the time, and is described as ‘a quiet Victorian icon’ by Annie Gray in her excellent book At Christmas We Feast (2021).[1] It is associated with this time of year because of its main ingredient: puréed chestnuts, and it deserves a comeback.

According to Eliza Acton, the pudding was invented by the famous Marie-Antoine Carême,[2] but it is not the case. In one of her best (and most obscure) books, Food with the Famous, Jane Grigson informs us that it was actually ‘invented by Monsieur Mony, chef for many years, to the Russian diplomat, Count Nesselrode, in Paris.’[3] Annie Gray took the research step further: the first printed recipe appears in Carême’s book L’Art de la Cuisine Française. In the original French version, he tells us he got the recipe from Mony, but in the English translation, he claims he – Carême – invented it.[4] Odd.

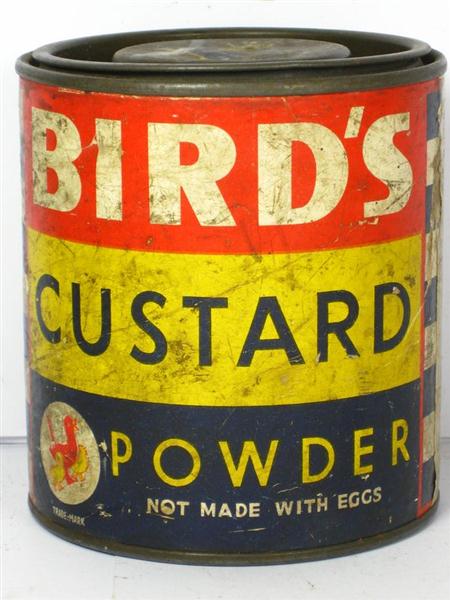

Recipes do vary, though chestnuts are essential (unless you are Agnes Marshall, who asks – rather controversially – for almonds, in her Book of Ices[5]). Other ingredients include glacé and dried fruits, vanilla and maraschino liqueur – an essential. in my book, but some recipes suggest using brandy or rum as alternatives. There is a custard base, but the mixture is not churned like regular ice cream: this is a no-churn affair. It’s prevented from freezing to a solid block with the addition of airy whipped cream and Italian meringue.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

Recipe

There are several stages to making this pudding, and you need to start making it at least two days before you want to eat it. Don’t let the making of egg custard sauces and Italian meringues put you off. However, a good digital thermometer and electric beater are essential.

Serves 8

For the pudding:

60 g chopped raisins or mixed fruit (currants, raisins and sultanas)[7]

60 g chopped candied peel or Maraschino cherries

80 ml maraschino

1 vanilla pod

300 ml single cream

3 egg yolks

160 g light brown sugar

160 g caster sugar

3 tbs/45 ml water

2 egg whites

300 ml whipping cream

440 g can or 2 x 200 g packets of unsweetened chestnut purée

To garnish: Maraschino cherries or candied chestnuts

For the custard sauce:

300 ml single cream or half-and-half whole milk and cream

50 g caster sugar

4 egg yolks

Around 25 ml maraschino (see recipe)

Soak the dried fruit and peel or cherries in maraschino overnight.

Next day, split the vanilla pod lengthways and scrape out the seeds and place both pod and seeds in a saucepan along with the single cream and heat to scalding point.

Meanwhile, put the egg yolks and light brown sugar in a mixing bowl, mix and then beat with a balloon whisk until it becomes a few shades paler. Pour in the hot cream by degrees, whisking all the time. Return the mixture to the pan and stir over a medium-low heat until it thickens – don’t let it boil, or you’ll get scrambled eggs – this should take about 5 minutes. If you want to use a thermometer to help you judge this, you are looking for a temperature of 80°C. Pass the mixture through a sieve into a tub, seal, cool and refrigerate until cold.

As it cools, make an Italian meringue: in a thick-bottomed saucepan, add the sugar and water. Place over a medium and stir until the sugar is dissolved, then bring it up to a boil. Insert your thermometer.

Meanwhile, put the whites in a bowl, ready to beat. When the temperature of the syrup hits 110-115°C, start beating the eggs to stiff peaks. When the syrup is 121°C, take the pan off the heat and trickle the syrup into the whites in a steady stream. Keep beating until almost cold – around 10 minutes – then cool completely. Whip the whipping cream until floppy.

Now the Nesselrode pudding can be assembled. Mix the chestnut puree into the cold, rich custard; you may need to use your electric beater to make the mixture smooth. If you like, pass the mixture through a sieve. Using a metal spoon, fold in the cream, then the meringue. Take your time – you don’t want to lose all of the air you have introduced to the meringue and cream. Strain the fruits (keep the alcohol) and fold those into the mixture.

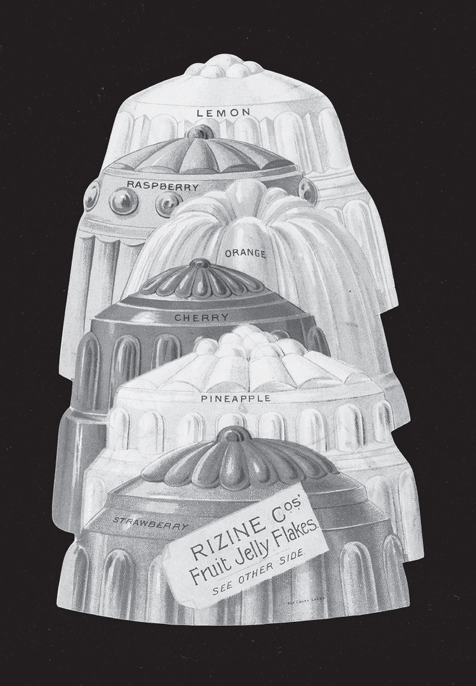

Select your mould – a generous 2 lb/900 g loaf tin is best, but you can use a pudding basin, or anything you like, as long as it has a volume of around 1.5-1.6 litres – and line it with cling film. Gingerly pour or ladle the mixture, cover with more cling film and freeze overnight.

Now make the custard sauce as you normally would – there’s a full method here – flavour with the strained alcohol. Taste it and add more booze if desired. When it tastes just right, add an extra half shot. Cool, cover and refrigerate.

To serve:

Remove the pudding from the freezer 30 to 40 minutes before you want to serve it. At the same time, place the custard sauce in the freezer so that it can get really cold.

Turn out the pudding onto a serving plate, remove the cling film, clean up the edge with kitchen paper and garnish. If the pudding is a bit of a mess around the edge, pipe some whipped cream around it. Pour the ice-cold custard sauce into a jug and serve.

Note: to make nice, neat cuts, pour hot water into a tall mug or (heat-proof) glass and heat up a serrated knife; this heat and a gentle sawing motion should result in clean cuts.

Notes

[1] Gray, A. (2021) At Christmas We Feast: Festive Food Through the Ages. Profile.

[2] This earliest mention of the pudding in the many editions of Acton’s classic Modern Cookery was the 14th. Acton, E. (1854) Modern Cookery for Private Families. 14th ed. Lonman, Brown, Green, and Longhams.

[3] Grigson, J. (1979) Food with the Famous. Grub Street.

[4] Gray (2021)

[5] Marshall, A.B. (1885) The Book of Ices. William Clowes and Sons.

[6] Ibid.

[7] When I made the pudding for the blog, I decided to forego chopping the fruit, wanting nice, big, plump fruits. A mistake: the large pieces sank – rats!