Summer pudding is one of the best and one of the most surprisingly versatile puddings there is. It’s also great fun to make and seeing as the first soft fruits crops are coming in, I thought I’d share my recipe with you. Before I do though, I should get the uninitiated up to speed on this quintessentially British dessert.

Summer pudding is typically a mix of red summer soft fruits lightly poached and set in a pudding basin that has been lined with berry juice-soaked white bread. For many, the thought of cold soggy bread makes them feel a little queasy, but they shouldn’t because the texture is not as one would expect; it is soft and giving and nothing like the texture of soggy bread in hot broth, for example. One way it is versatile, however, is that you can use other things in place of the bread, such as slightly stale slices of madeira or pound cake. Indeed, this is the way I prefer to make it because this way, you quickly dip the cake in the juices (otherwise it just breaks apart) unsoggy and much more pleasing in texture, rather like the base of a trifle, though a less vibrant colour. It’s swings and roundabouts isn’t it.

The other way in which it is versatile is in the fruit you can use. There are many who are purists who insist you use 100% raspberries, for others there must be at least 50% redcurrants, and some think there is no place for the strawberry. These people are all pudding fascists. I’m not picky and I go for what’s in season at the time: gooseberries, red, white or blackcurrants, blueberries, blackberries, strawberries, whatever.

The summer pudding goes back to the nineteenth century as far as I can see, the earliest mention of something resembling it popping up in an American publication from 1875. It describes a hot pudding consisting of currants and sugar steamed in a basin lined with bread. I’ve also found a British ‘midsummer pudding’ that is also hot but uses a suet crust and is – oddly – more recent. A cold pudding made in the manner we know and love today appears around the turn of the twentieth century under the curious name of ‘hydropathic pudding’, so called because it was introduced to ladies at health spas as a low-calory alternative to regular stodgy suet puddings.

I have also found other recipes for autumn pudding and winter pudding, that have swapped the summer fruits for stewed apples, pears and dried fruit or blackberries, sometimes switching white bread for brown.

This is my recipe and it makes just one small pudding, unlike most other recipes that make a giant one using a re-mortgage worth of redcurrants, so this is the recipe for those who do not grow their own. In fact, all you should need are two or three punnets of soft fruit.

Serves 4:

300 g ripe soft summer fruits (raspberries, blackcurrants, red or white currants, blueberries, strawberries, gooseberries etc)

80 – 100 g caster sugar

A shot of an appropriate liqueur such as Chambourd, optional

2 or 3 slices slightly stale bread, crusts removed, or one stale madeira or pound cake, cut into 7 to 10 mm slices

To serve: clotted cream or lightly whipped double cream

Rinse the fruit, cutting any large fruits such as strawberries and gooseberries into halves or quarters as appropriate. Scatter in the sugar, but don’t make things too sweet, especially if using cake rather than bread. However, if you are using green gooseberries you many want to shake in the full quota. Pour in the liqueur if using, stir, cover and leave to macerate overnight.

Next day, put the contents of the bowl in a saucepan over a medium heat. Stir gently to dissolve the sugar, trying not to squish the fruit too much. When dissolved, bring to a boil and simmer gently for two minutes, then turn off the heat. Set aside to cool down.

Cut your slices of cake into enough pieces to line a 450 ml / 1 pint pudding basin. I cut rectangles that taper slightly at one end so that they fit nicely.

Dip each piece of cake or bread in the juicy warm fruit and press into the inside of the basin. Repeat with more slices until you have covered the sides, then cut a circle to fit in the bottom. Be careful if using cake at this point as they are prone to break when soggy.

Now spoon the fruit mixture into the pudding, packing everything in well with the back of a spoon.

Cut more cake or bread to make a lid, press down hard with fingers, then place a saucer on top with a suitable weight and place in the refrigerator overnight.

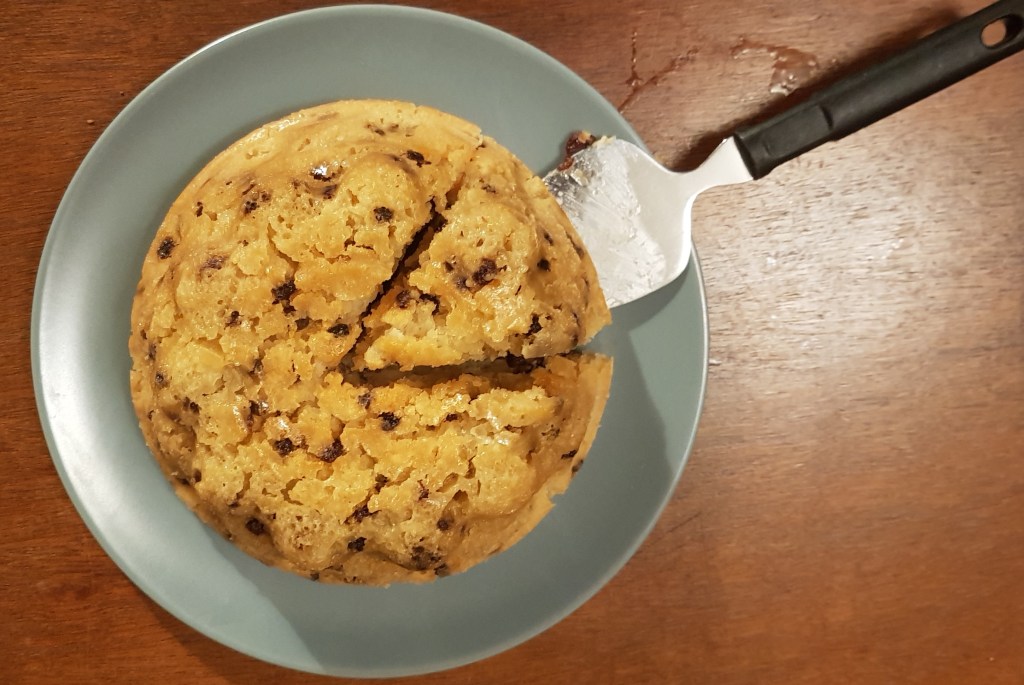

When ready to serve, loosen the pudding a little with a knife before inverting it on a plate. Be patient as the pudding leaves the mould – do not be tempted to hurrying things, lest disaster strikes. If using a plastic basin, massage it a little to help it along.

Serve with any remaining juice or fruit and the cream.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

References:

Cookery from Experience (1875) Sara T Paul

English Food (third edition; 1992) Jane Grigson

Pride and Pudding (2015) Regula Ysewijn

‘Summer Pudding’, Foods of England website http://www.foodsofengland.co.uk/summerpudding.htm

‘Winter Pudding’, Foods of England website http://www.foodsofengland.co.uk/winterpudding.htm