Welcome to the first of a two-part special all about Burns Night.

Burns Night, celebrated on Robert Burns’ birthday, 25th January, is a worldwide phenomenon and I wanted to make a couple of episodes focussing upon the night, the haggis, but also the other foods links regarding Scotland’s national poet, Robert Burns.

The episode is available on all podcast apps, but can also be streamed here:

Burns was born in Alloway, Ayrshire on 25 January 1759 and he died in Dumfries on 21 July 1796 at just 37 years old.

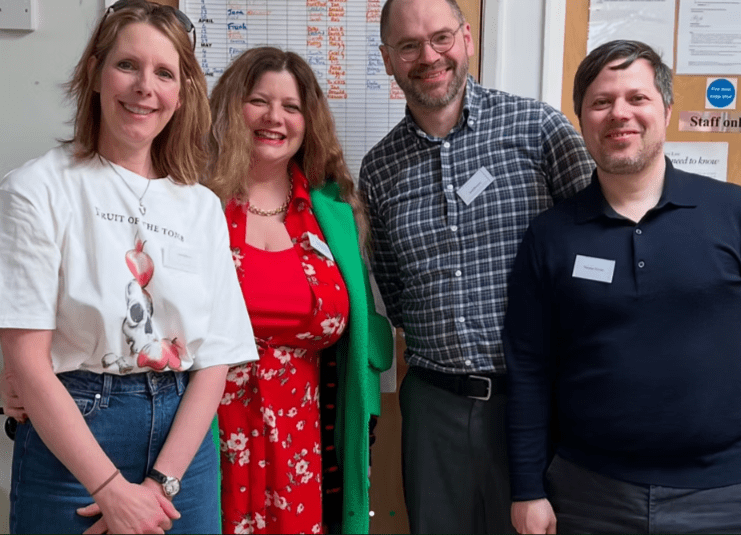

My guest today is food historian Jennie Hood, who has written an excellent article for the most recent edition of food history journal Petit Propos Culinares, entitled ‘A History of Haggis and the Burns Night Tradition’, so she is the perfect person to speak with on this topic.

Jennie Hood hails from Ayrshire, just like Robert Burns, and we talk about the origin of Burns Night, but we also talk about the medieval origins of the most important food item on the Burns supper plate – the haggis.

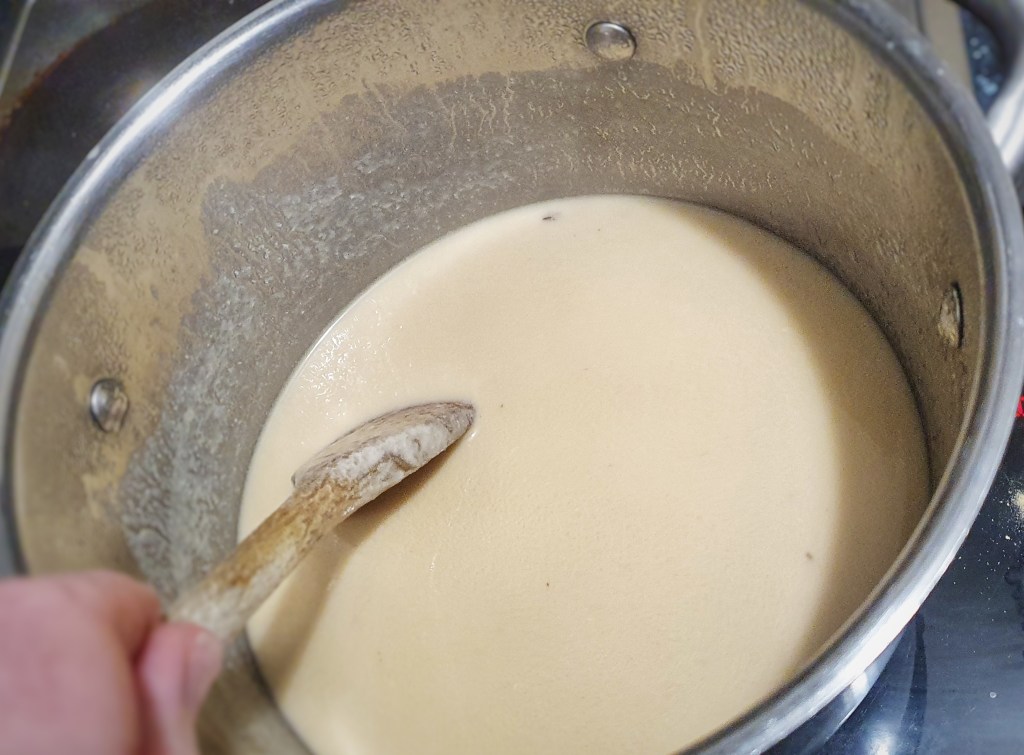

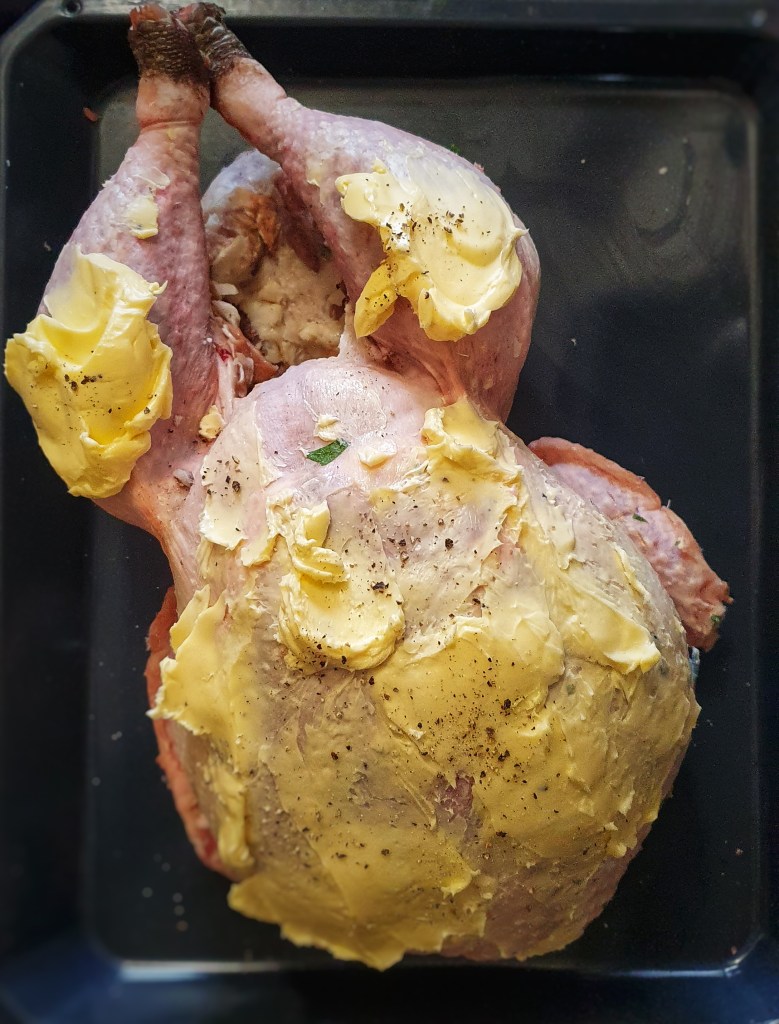

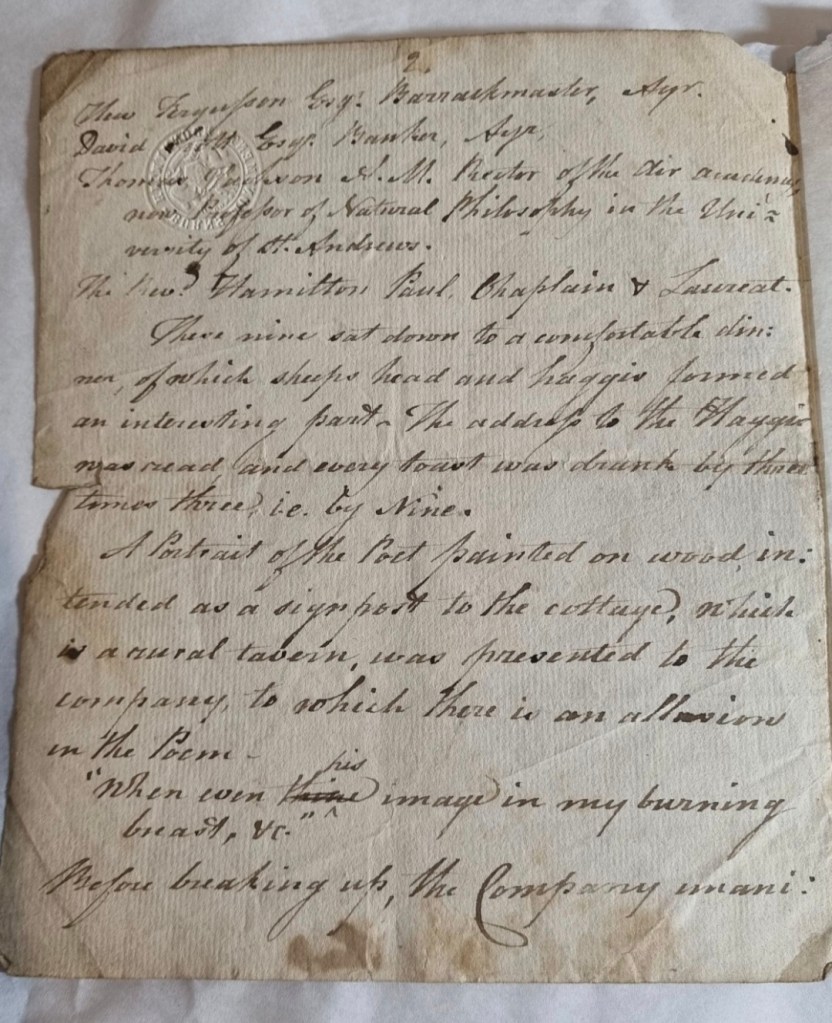

Things covered include the first English recipes for haggis, what makes a haggis a haggis (not as easy a thing as you might expect), Burns’s poem Address to a Haggis and what it tells us about haggises in Burns’s day and how the first Burns suppers started and gained such popularity, amongst many other things.

Follow Jennie on social media: Threads/Instagram @medievalfoodwithjennie; Bluesky @medievalfoodjennie.bsky.social; Facebook https://www.facebook.com/medievalfoodwithjennie

Company of St Margaret, Jennie’s late medieval and renaissance re-enactment group

Issue 133 of Petits Propos Culinaires

If you can, support the podcast and blogs by becoming a £3 monthly subscriber, and unlock lots of premium content, including bonus blog posts and recipes, access to the easter eggs and the secret podcast, or treat me to a one-off virtual pint or coffee: click here.

This episode was mixed and engineered by Thomas Ntinas of the Delicious Legacy podcast.

Things mentioned in today’s episode

The Good Housewife’s Jewel by Thomas Dawson

The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy by Hannah Glasse (‘Haggas’ recipe p.291)

The Robert Burns World Federation

Address to a Haggis by Robert Burns

Suzanne MacIver’s recipe for haggis

Ivan Day’s recipe for hack pudding

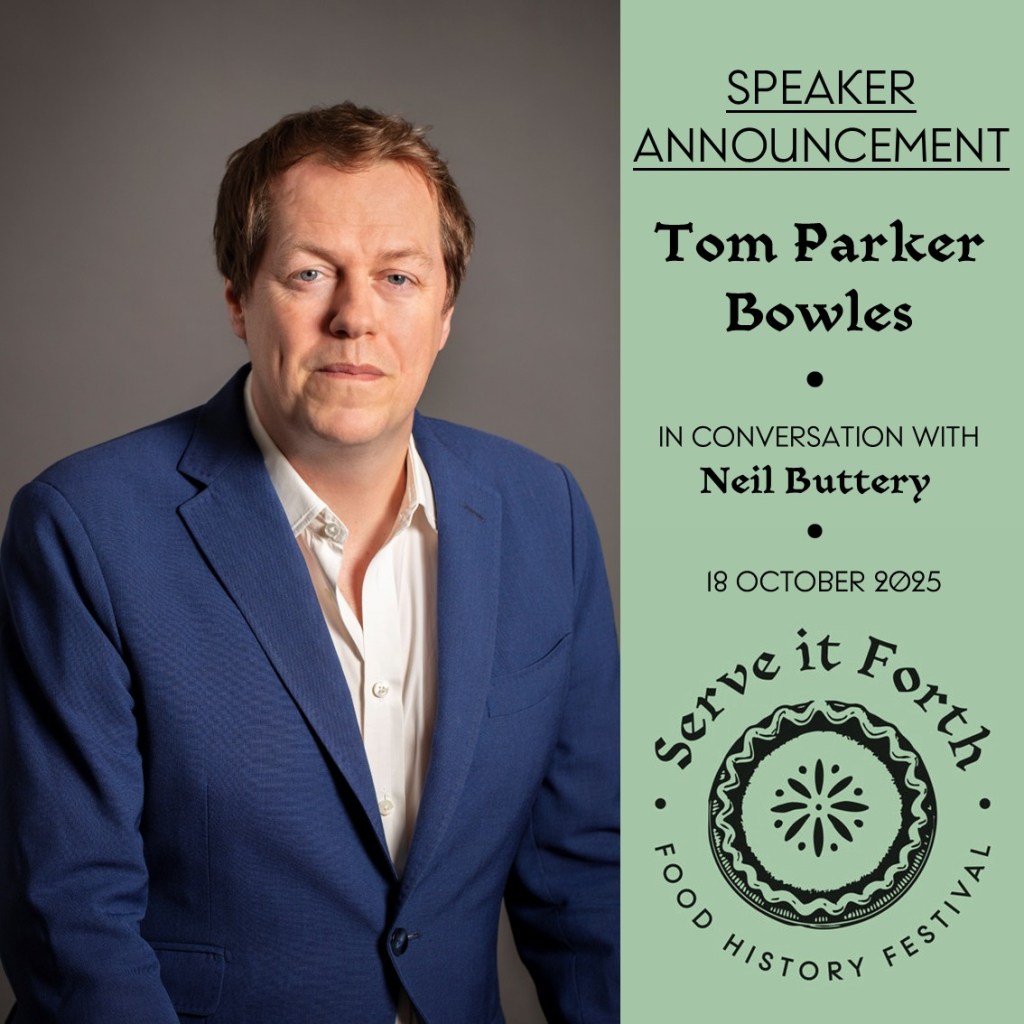

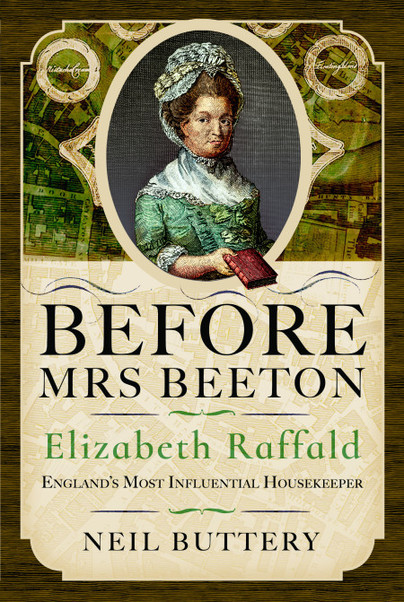

The Philosophy of Puddings by Neil Buttery

BBC Countryfile January 2026 edition

Royal Births, Marriages & Deaths website (Channel 5)

Previous pertinent blog posts

Lamb’s Head with Brain Sauce (from Neil Cooks Grigson)

Previous pertinent podcast episodes

The Philosophy of Puddings with Neil Buttery, Peter Gilchrist & Lindsay Middleton

Neil’s blogs and YouTube channel

The British Food History Channel

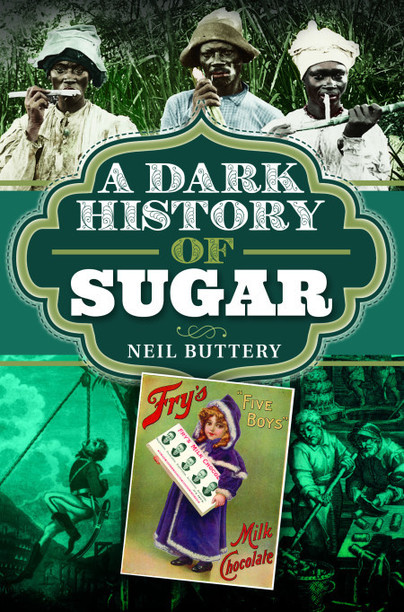

Neil’s books

Before Mrs Beeton: Elizabeth Raffald, England’s Most Influential Housekeeper

Knead to Know: a History of Baking

Don’t forget, there will be postbag episodes in the future, so if you have any questions or queries about today’s episode, or indeed any episode, or have a question about the history of British food please email me at neil@britishfoodhistory.com, or on twitter and BlueSky @neilbuttery, or Instagram and Threads dr_neil_buttery. My DMs are open.

You can also join the British Food: a History Facebook discussion page: https://www.facebook.com/groups/britishfoodhistory