I recently had a go at making a fresh blood black pudding, taking inspiration from cookery books from the 16th and 17th centuries. The fresh blood was very kindly sent to me by Matthew Cockin and Grant Harper of Fruitpig, Britain’s last craft producer of fresh blood black pudding, who are also sponsoring the ninth season of The British Food History Podcast. Listen to the episode we recorded here:

We also talked about their hog’s pudding – a type of white pudding – and I felt I had to complete the set and make an Early Modern white pudding as well.

We know where we stand with black puddings: we expect them to be made largely of blood, cereal and fat, but what about white puddings? These are more mysterious, I feel. Modern white puddings are made from ground pork, pork fat, breadcrumbs and rusk or oats, plus lashings of white pepper, and are today associated largely with Scotland and Ireland. There used to be a rich diversity of white puddings right across Britain and Ireland, their contents highly variable, the only prerequisite being that the finished product would come out white. In the Early Modern Period, they were lavish ‘puddings of the privileged’[1], and had more in common with French boudin blanc than modern British white puddings. There was plenty of eggs, milk and cream, and the meat used (if any) was suitably pale in colour: Kenelm Digby’s recipe contained the meat of ‘a good fleshly Capon’ as well as streaky bacon,[2] Thomas Dawson’s was made with a calf’s chauldron, i.e. intestines.[3] Some recipes contain no meat at all: rice pudding could be counted as a form of white pudding in this context. Things do begin to get confusing, however, because some white puddings made with pork are called hog’s puddings, but only some. As Peter Brears wrote in an article on white and hog’s puddings:

On studying these recipes, one rather surprising fact becomes particularly obvious; there is no material significance in the various names given to such puddings. Whether called hog’s or white puddings, their ingredients might be identical, or quite disparate, while many contain absolutely no pork whatsoever.[4]

Today, hog’s puddings are associated with Devon and Cornwall. Fruitpig’s hog’s pudding uses a base of bacon and oats. We can muddy the water even further because a hog’s/white pudding if made with pig’s liver could also go by the name of leverage pudding.

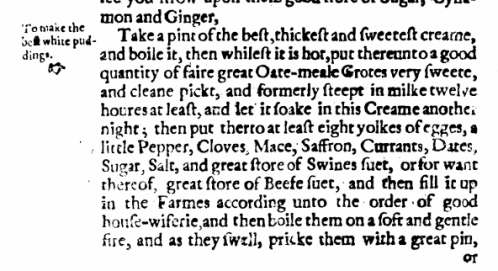

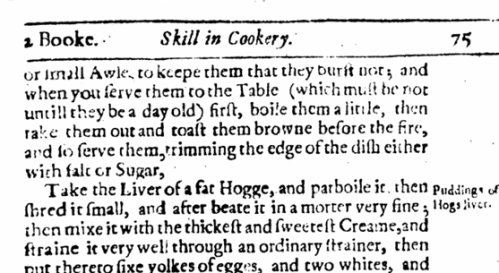

After a great deal of flicking through cookery books, I decided to make Gervase Markham’s white pudding from his classic The English Housewife (first published 1615), mainly because I had most of the ingredients in the house.

As you can see, Markham’s recipe contains no meat (aside from the beef suet and the pudding casings themselves).[5]

I have to say, they were a triumph! They freeze well and are easy to reheat. When it comes to serving them, let them cool for 5 minutes before cutting into them. The best way I have discovered to eat them (so far) is with crispy smoked bacon and golden syrup. Breakfast of champions.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

Recipe

Makes 6 x 375 g (approx.) puddings:

500 g cracked oat groats or pinhead oatmeal (steel-cut oats)

500 ml whole milk, plus 2 tbs for the saffron (and possibly extra, see recipe)

Around 2.5 metres of beef casings

600 ml whipping or double cream

150 g suet

130 g caster sugar

2 whole eggs plus 4 egg yolks

60 g sliced dates

60 g currants

¼ tsp ground black pepper

1/8 tsp ground cloves

¼ tsp ground mace

2 tsp salt

A 2-finger pinch of saffron

The day before you want to make your puddings, place the oats in a bowl or jar and pour over the milk. Cover and refrigerate. Soak your beef casings in fresh water, cover and refrigerate too.

Next day make the pudding mixture: in a large mixing bowl add the milk-soaked oats, cream, suet, sugar, eggs, dates, currants, ground spices and salt. Stir well. Warm up the 2 tbs of milk, add the saffron strands and allow them to infuse and cool, then stir into the mixture.

Now let everything meld together for a couple of hours so that the whole mixture is the consistency of spoonable porridge. If your oats were particularly absorbent, you may need to loosen the mixture with a few tablespoons of extra milk.

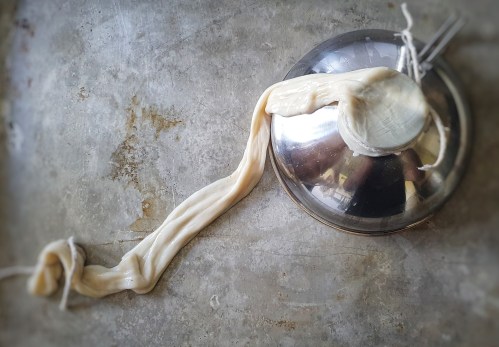

Cut the soaked beef casings into 35 cm lengths and tie the ends securely with string. Now it’s time to attach a funnel to the other end of your first length of gut. I used a jam funnel and secured it with more string.

Hold the funnel in one hand and add small ladlefuls of mixture into the gut. It should slip down relatively easily. Keep the funnel raised and try to massage out any large air bubbles. When the gut is around two-thirds to one-quarter full, remove the end tied to the funnel, press out any air and tie with more string. The casings are slippery and so you must make sure that the knots are made at least 2.5 cm/1 inch from the ends. I found 350 g mixture to be a good amount. Now tie the ends together with more string to make that classic pudding shape.

Keep them covered as you get a large pot of water simmering.

Cook the puddings in batches: drop three into the water and let them gently poach for 35 minutes – there should just be the odd bubble and gurgle coming from the cooking water. You must pop any bubbles immediately with a pin, otherwise the puddings will burst open. Turn the puddings over every 7 or 8 minutes to make sure both sides are cooked evenly.

When cooked, fish the puddings out and hang them up to dry for a few hours, then refrigerate.

To cook the puddings, poach them in more water for around 15 minutes, turning occasionally.

[1] Davison, J. (2015). English Sausages. Prospect Books.

[2] Digby, K. (1669). The Closet of Sir Kenelm Digby Opened (1997 reprint) (J. Stevenson & P. Davidson, Eds.). Prospect Books.

[3] Dawson, T. (1596). The Good Housewife’s Jewel (1996 Editi). Southover Press.

[4] Brears, P. (2016). Hog’s Puddings and White Puddings. Petits Propos Culinaires, 106, 69–81.

[5] This recipe is from the 1633 edition: Markham, G. (1633). Country Contentments, or The English Huswife. J. Harison.