The Mediaeval Period is a vast expanse, lasting around one thousand years from the fifth century to the fifteenth, and so encompasses a substantial slice of history. It is flanked on one side by the Classical Period, the end of Roman occupation ended that one; at the other, the start of the Modern Age marked by the fall of the Plantagenet dynasty, the rise of the Tudors and the Age of Discovery. Being bookended like this, the Mediaeval Period is also sometimes called the Middle Ages.

A 13th Century farming scene: Le Régime des princes, 1279.

During this period, technology and agriculture advanced greatly, but everyone was at the mercy of the elements and entire harvests were often lost creating famine. The knowledge and skill required of the mediaeval farmer was therefore ‘vital and important’; a close eye had to be kept on the seasons, weather and general climate. Planning and forethought were essential, especially when things did not go to plan, for nothing could be grown in the winter months, so the community (which may just have been a single household) depended upon the stores built up over the summer and autumn. They were slaves to the calendar.

Wet, cold weather in spring and summer could spell disaster later in the year if food, especially grain, was not rationed and stored properly; what was grown was grown, and when autumn hit no plants could be cultivated from seed. Fighting off damp and vermin was important too; not just because it was food for the people, but for livestock too. Whole stores have been destroyed by mould. The best way to take down a village or town was to destroy the grain stores.

A modern reproduction of a mediaeval grain store (Village de l’An Mil)

Efficiency was also key: corn and other cereal crops (such as oats in more northern climes) were collected and stored, poultry such geese would eat fallen grains difficult for people to pick, and would hopefully fatten. These birds – and other livestock – would all be slaughtered, the offal being eaten immediately with most of the meat preserved in salt and smoked in chimneys. Only the animals required for breeding the next year would be kept, but in poor years even these beasts had to be killed. This had huge repercussions; not only would there be no breeding stock next spring, but also no oxen to plough the fields to plant the corn. With few crops, people were essentially reduced to a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, trapping wild animals and foraging for pignuts, berries and leaves. Famine and its associated diseases followed, especially when one throws in the Black Death in the latter centuries of this period.

Life for most was relentlessly gruelling and cruel, especially in the first Anglo-Saxon half of the period and no one was exempt; of course, it was peasants and slaves who would be the first to feel the effects of this, those ranked higher were better protected, but as a town generally ate the food it produced itself, effects quickly trickled down.

Things did improve in England when William the Conqueror/Bastard hopped over the channel with his Norman mates; an unprecedented amount of food and wine was imported from Normandy, France and other countries. Of course, only the Norman high-rankers benefitted. A major blow to the common man was the Conqueror’s implementation of strict hunting laws. Only the king, nobles, and those given special permission could hunt in the forests, anyone caug were punished severely, even in very lean times (for more information on this topic see this previous post).

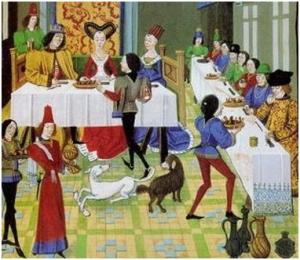

Mediaeval Feast

A noble mediaeval feast, notice the dogs have free reign!

In times of plenty great feasts were held, especially by the kings and nobles of the age; one had to show ones wealth, and the best way to do this was by displaying how productive your land was with huge amounts of meat, poultry, game and fish. In this period it was all about quantity and quality.

In the twelfth century, the first crusades opened up a whole new world of excitement and opulence for the rich, as exotic fruits and spices were brought back from the Holy Land along the newly-formed spice routes, adding a whole new dimension to high-class feasting.

In the early Anglo-Saxon period, and in smaller towns and for Christian feasts and celebrations, feasts tended to be a community-wide affair, with everyone eating together in a great hall. There was a strict system where one sat, however, the top table being reserved for the special guests.

Most feasts followed the same basic pattern; several courses each made up of several dishes, with everyone collecting food from the tables at which they were sat. Large flat squares of hardened bread called trenchers were used as plates, which were then given to the poor to eat afterwards (it was also much cheaper to make disposable bread plates than to buy or produce earthenware ones.)

The first course started with the archetypal roast boar’s head, it was often extravagantly decorated with brightly coloured pastry pieces as well as silver and gold leaf. It was symbolic of a time gone past – the head of the beast killed for the night’s feast, and was not generally eaten. Served alongside the head was brawn, a kind of terrine made from a pig’s head, and mustard. I have made brawn myself and it is very delicious; it’s amazing how much meat there is on a pig’s head!

Immediately after the boar’s head and brawn, the large roasted animals were brought in: pigs, mutton, kid, swan, venison and ‘noble’ game such as hare.

The second course was made up of the smaller and lesser animals: chickens, rabbits, songbirds and bitterns for example, and meat broths.

The third course was essentially the same as the third, but included fish and and more dainty dishes, like eggs in jelly, custard tarts, marzipan and comfits.

There would also be many pies, some small and some huge, and some that were there just for show; the most famous being the ‘four-and-twenty blackbirds baked in a pie’. It was common to put live animals in huge pastry cases so that when it was cut open, they would fly (or crawl) out much to the guests’ amusement. Such solettes, or subtleties, were part of many feasts. Great feasts had a whole course made up of dishes that were simply there to be looked at!

The planning and manpower required to carry off these huge events, the food served would be dependent upon season. My next few posts are going to about mediaeval food – hope you enjoy!

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

References:

Curye on Inglyche (1985), Eds. Constance B Hieatt & Sharon Butler, Oxford University Press

Food in England (1954) by Dorothy Hartley, Little Brown & Company

A History of English Food (1998) by Clarissa Dickson-Wright