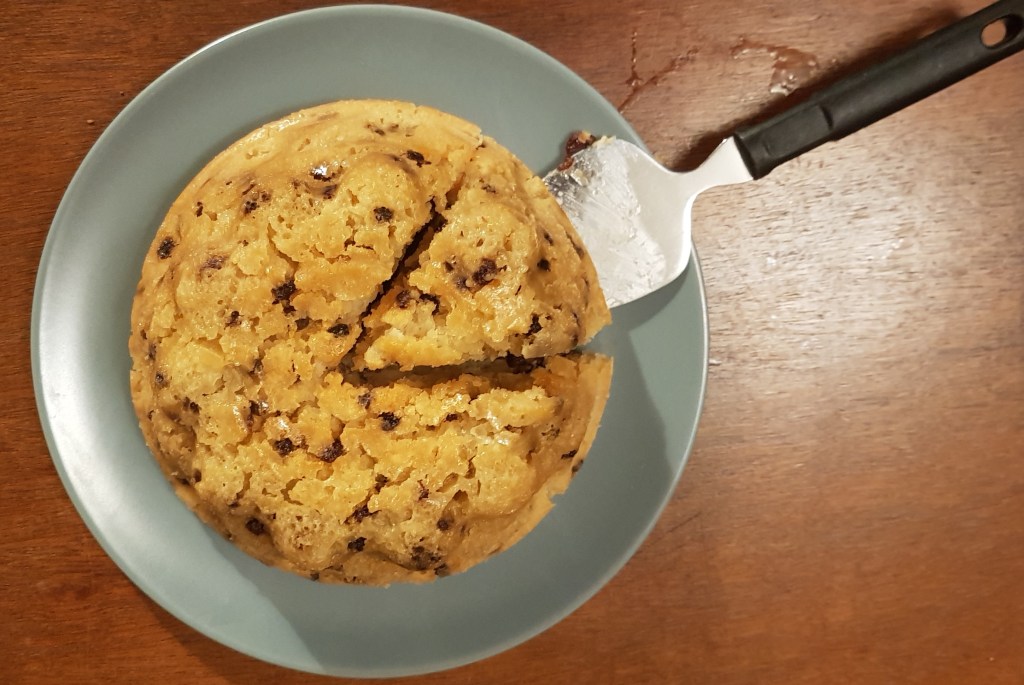

Suet is the essential fat in many British puddings, both sweet and savoury, as well as stuffings and dumplings, mincemeat at Christmastime and – of – course suet pastry. It makes some of my most favourite British foods. It’s role is to enrich and lubricate mixtures, producing a good crust in steamed suet puddings.

Suet is the compacted, flaky and fairly homogenous fat that is found around animals’ kidneys, protecting them from damage. Here’s a very quick little guide to buying and using it in recipes.

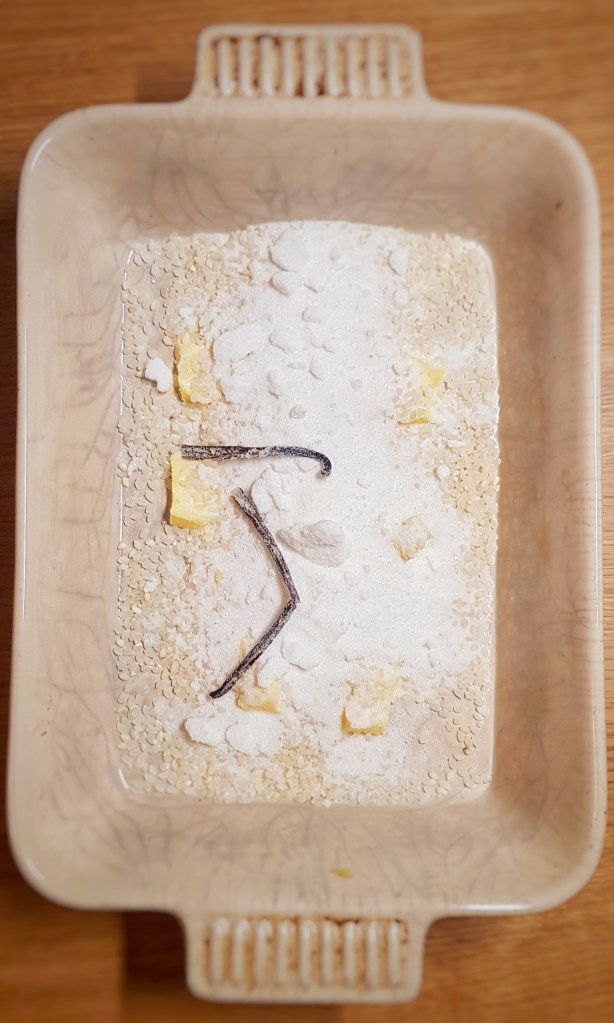

Flaky fresh beef suet

Flaky fresh beef suet

Don’t be put off by suet – I served up Jam Roly-Poly to a group of 18 American undergraduates recently, and they’d never heard of a suet pudding before. They all came back for seconds!

Several recipes already on the blog use suet:

- The forcemeat balls in Mock Turtle Soup

- The dumplings in Brown Windsor Soup

- Spotted Dick

- Jam Roly-Poly

- Jane Grigson’s Orange Mincemeat

- Mrs Beeton’s Mincemeat

Fresh Suet

Fresh suet can be bought from your local butcher at a very low price. Most commonly available is beef suet and it can be used in any recipe in the book. You can also buy lamb and pork suet – and sometime venison – which are all great when using the meat of the same animal in the filling (e.g. Lamb & Mint Suet Pudding). Pork suet is sometimes called flead or flare fat. Sweet suet puddings, however, require beef because it is flavourless, whilst lamb is distinctly lamby; not great in a Jam Roly-Poly.

Fresh suet can be minced at home or by your butcher or can be grated. I prefer to do the latter, as it’s quick and easy. You must avoid food processors however, as you end up with a paste. Grater or mincer, you will need to remove any membranes and blood vessels – much easier to do as you grate, hence why it’s my preferred method.

Freshly-grated beef suet

Freshly-grated beef suet

I find it best to buy enough suet for several puddings, grate it and then freeze it. Fresh suet can be kept frozen for up to 3 months.

Preparatory Suet

Although not as good as fresh, packet suet bought from a supermarket is a perfectly good product and store cupboard standby. Atora is the iconic brand producing a shredded beef suet as well as a vegan alternative; these vegetable suets are made from palm oil and are therefore somewhat environmentally unfriendly. However, Suma produce one that is made from sustainably sourced palm oil, so keep a look out for that in shops.

Preparatory suet can be switched weight-for-weight in any recipe unless otherwise indicated.

And that’s my very quick beginners’ guide to suet, have a go at cooking with it, you won’t be disappointed.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.