The weather outside may be miserable and the evenings still long, but luckily there is a little fleeting sunny surprise popping up in grocers around the country that can perk us up no end; at least if you know where to find them. It is Seville orange season and a small window of just a few weeks is all we have to cook with this delicious fruit.

The Seville orange is very bitter and is only really grown in Spain for us British to make our Oxford marmalade. What a treat home-made marmalade is; oranges, water and sugar that is all that are needed to produce such a delightful, very British preserve. If you have never made your own, have a go before they are all disappear again.

Like all citrus fruits, the Seville orange comes originally from China. It was imported on trade routes via Italy, to the Mediterranean countries of Europe. All of these original orange trees were bitter in flavour like the Seville. In the first half of the 17th century, sweet orange trees were delivered to the Portuguese coast by ship. These sweet oranges quickly superseded the bitter ones, that is for that small area of Spain that still grows them.

The flowers of Seville oranges are also used to make orange flower water, another of my favourite ingredients.

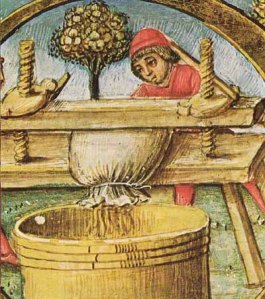

Rabbit with Red Legged Partridge and Seville Orange by Jean-Baptiste Chardin 1728-29

Below is a recipe for Seville orange marmalade, but it is useful to know that the zest and juice of these oranges go very well with game and some shellfish such as scallops as the above painting shows.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

Seville Orange Marmalade

Oddly enough, marmalade was not made from Seville or any other orange at first, but quince (a knobbly cousin of apples and pears). It did come from Spain though, in fact the Spanish word for quince is marmalada. Every day’s a school day.

This recipe is Jane Grigson’s and it is a good strong bittersweet ‘Oxford’ style marmalade.

Ingredients

3 ¼ litres water

1 ½ (3 lb) Seville Oranges

3 kg (6 lb) granulated sugar

Give your oranges a good scrub and place them in a preserving pan or large stockpot with the water. Bring to a boil and simmer for about 1 ½ hours until the oranges are tender.

Take them out with a slotted spoon. They will probably collapse in on themselves, but don’t worry about that. Let them cool a little, then halve them and scoop out their innards. Tie up the scooped-out pulp in a piece of muslin. If you want a soft set, just put the bag of pulp straight into the pan, if you want it well set, give it a good squeeze to get as much pectin out of the pith and into the liquor as possible (I’m a soft set man).

Next, shred the peel, you can be as careful as you want, and you can cut them as thick as you want. You can do this by hand or in the food processor by blitzing them using the pulse setting – be careful though, you don’t want a load of slurry. I’m usually dead against using food processors for this sort of thing, but I quite like the irregular pieces you get with this method. Tip them into the pan along with the sugar. Over a medium heat, stir until the sugar dissolves.

Now you need to be brave and bring it to a full rolling boil for at least 15 minutes , you need it very hot so that the marmalade can set. You have several options to test for a set, but I use a combination of a sugar thermometer and the wrinkle test. Pectin – a chemical that essentially glues plant cell walls together – will set to a gel at 105⁰C (221⁰F), so a thermometer is crucial if you want to know if you are getting close. It can take a while because water needs to evaporate to get five degrees above boiling point. Keep a close eye on it and when it gets close do the wrinkle test. For this test put a side plate in your freezer a little while before you want to make your marmalade, and when you’ve achieved 105⁰C (221⁰F), turn off the heat and spoon out a little of it onto your cold plate. Return it to the freezer for a couple of minutes. Push the jelly; if it wrinkles up, your pectin is set. If not, boil up again and retest after 10 minutes.

When ready, turn off the heat and allow it to cool for 15 minutes – this important step will stop your peel from floating to the top in a single layer – then pot into sterilized jars (bake them and their lids for 25 minutes at 125⁰C or 250⁰F).

![20121228_191019[1]](https://fix-quick.today/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/20121228_1910191.jpg)

![20121228_184345[1]](https://fix-quick.today/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/20121228_1843451.jpg)