In my book Knead to Know: A History of Baking, I made sure that there was a full chapter focussing on griddlecakes: food baked on hearthstones, bakestones and iron griddles. Of course, when writing the chapter, I took much inspiration from Jane Grigson’s baking recipes in English Food. I was surprised by the great variety. These days the English barely think beyond the crêpe.

It’s been a while since I posted a recipe for a griddlecake, and I have had this one, for singin’ hinnies, waiting in the wings for a while. These little cakes are a rather forgotten speciality of Northumberland. I first made these for the Neil Cooks Grigson project in its very early days and I didn’t do a great job of interpreting Jane’s recipe.[1] I have improved greatly since then. The real prompt to get this recipe out there was my conversation with Sophie Grigson, Jane’s daughter, for a recent episode of The British Food History Podcast all about Jane’s work. The topic of singin’ hinnies cropped up because Jane’s entry for it in English Food is particularly evocative. Listen to the episode here:

These griddlecakes, enriched with lard and butter and sweetened only by dried fruit, were eaten by all, and were especially at children’s parties where tuppeny and thruppenny pieces were hidden inside.[2] These once ubiquitous cakes were, for many families, sadly the ‘substitutes for the birthday cake [they] could not afford.’ The word ‘hinnie’ is a dialect one for honey, a term of endearment, and the ‘singin’’ refers to the comforting sizzle of the butter and lard from the cooking griddlecakes, although Jane does point out that ‘the singin’ hinnies made less of a song for many people as they could not afford the full complement of butter and lard.’[3]

I have found other mentions of singin’ hinnies elsewhere but recipes and descriptions are very vague. I did find two nineteenth-century descriptions that really emphasised their importance at the dinner tables of miners – Northumberland being very much a colliery county. The job required very calorific food, so these griddlecakes served an important function. One stated that ‘miner’s food consisted of plum pudding, roast beef and “singing hinnies”.’[4] Another, written by J.G. Kohl, a German travel writer, informs us that ‘[the colliers] even have dishes and cakes of their own; and among these I was particularly told of their “singing hinnies”, a kind of cake that owes its epithet “singing” to the custom of serving it hissing hot upon the table…They are very buttery, and must never be absent on a holiday from the table of a genuine pitman.’[5]

Jane reckons they are the second-best British griddlecake; for her, Welsh cakes take the top spot.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce and would to start a £3 monthly subscription, or would like to treat me to virtual coffee or pint: follow this link for more information. Thank you.

Recipe

I give you my interpretation of Jane’s recipe with more precise ingredients and method. I have found all other recipes to be either too vague in the amount of liquid that should be added, or, when specific, far too dry. I do hope you find this recipe clear; I know it must work because the hinnies sing loud and true as they cook on the griddle.

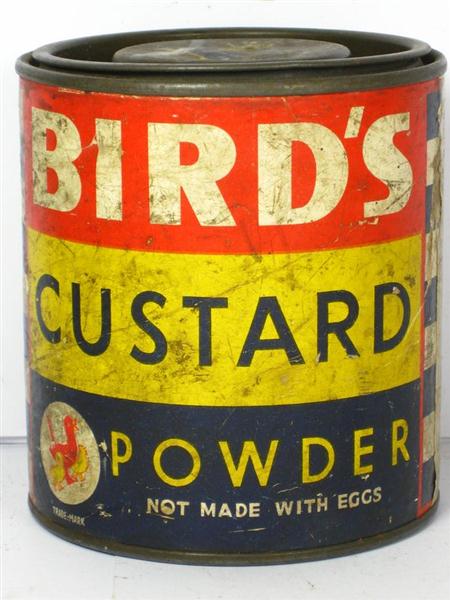

A proper singin’ hinnie should be made with equal amounts of butter and lard. If you are vegetarian, avoid using shortening such as Trex, instead go posh and use all butter.

Makes 24 to 28 griddlecakes

500 g plain flour, plus extra for rolling

1 tsp baking powder

¾ tsp salt

125 g lard, diced

125 g butter, diced

180 g dried mixed fruit

220-240 ml milk

Extra lard for frying

Extra butter for buttering the insides of the singin’ hinnies

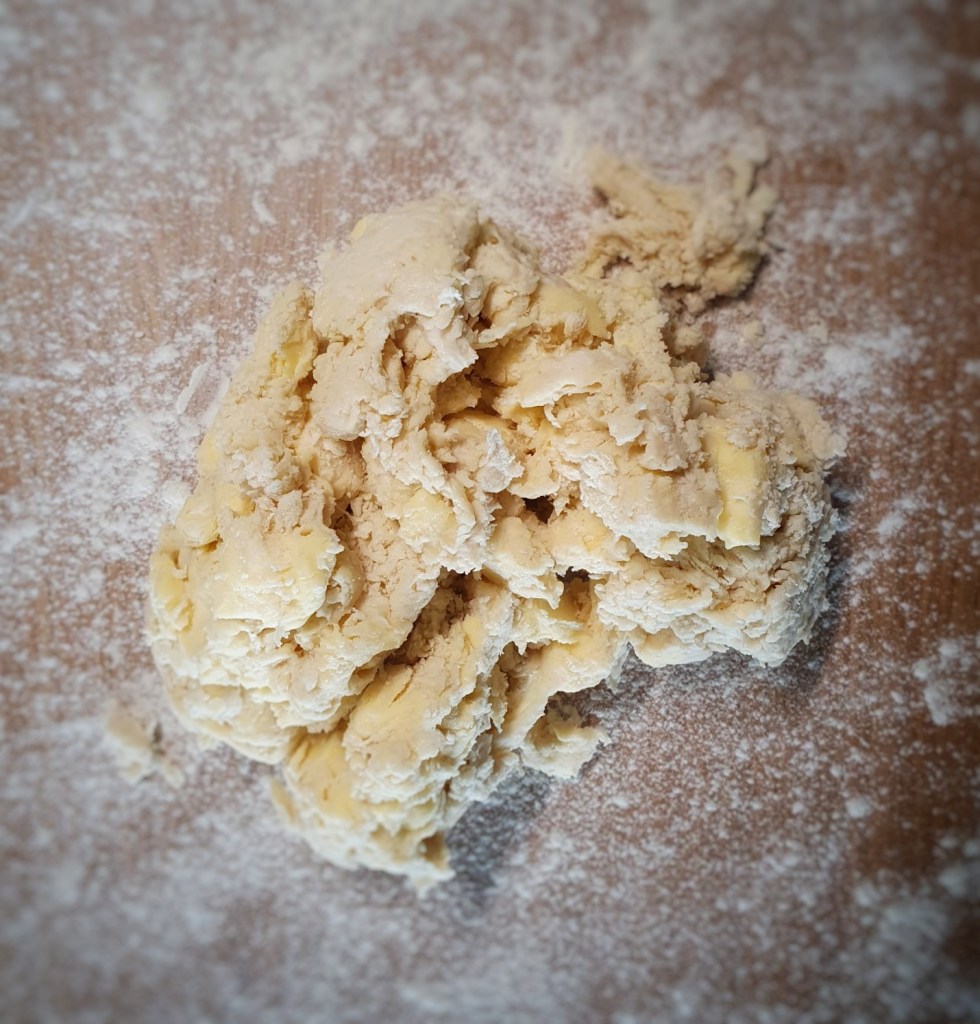

Mix the flour, baking powder and salt in a bowl, then rub in the lard and butter until the mixture resembles breadcrumbs, then add the dried fruit and mix again.

Make a well in the centre, add most of the milk and mix to make a nice soft dough – it’s a good idea to use the old-fashioned method of combining everything using a cutting motion with a butter knife; that way you ensure the liquid is combined with the other ingredients without overworking the gluten in the flour. Add the remaining milk should there be any dry patches.

Lightly flour your worktop and knead the dough briefly so that it becomes nice and smooth. Let it rest as you get your bakestone, griddle or pan ready.

Place the bakestone on a medium heat and allow to get to a good heat; because there is no sugar in the mixture, the cakes don’t burn easily.

As you wait for it to heat up, roll the dough on a lightly floured surface to a thickness of around ¾ centimetre and cut out rounds. I used a 7-centimetre cutter, but 6- or 8-centimetre cutters will be fine. You might find it easier to cut them out if you dip your cutter in flour and tap away any excess. Reroll the pastry and cut out more.

Take a small piece of lard, quickly rub it over the surface of the bakestone and cook your first batch: mine took 5 to 6 minutes on each side to achieve a nice golden brown colour on the outside and a fluffy interior (I sacrificed one to check inside). Split each one with a knife and add a small pat of butter, close and keep them warm in the oven on a serving plate as you cook the rest.

Serve warm with your favourite toppings. I went with good old golden syrup (and an extra knob of butter).

Notes

[1] Read the original post here.

[2] i.e. two-penny and three-penny coins.

[3] Grigson, J. (1992) English Food. Third Edit. Penguin.

[4] Fynes, R. (1873) Miners of Northumberland and Durham. J. Robinson.

[5] Kohl, J.G. (1844) England, Wales and Scotland. Chapman and Hall.