A classic British nursery pudding, the treacle tart is much-loved. It is probably the ultimate child’s dessert because it is so unbelievably sweet; it makes my teeth hurt just looking at one! That aside, I have never really lost my sweet tooth and I love treacle – meaning golden syrup of course in this case (see here for a post on treacle). Treacle tart was very popular with poorer families – the two main ingredients being bread and treacle – no expensive fruits and spices here.

The pudding itself as we know it has only been in existence since the late nineteenth century since golden syrup was invented in the 1880s. However, the earliest recipe I have found for a treacle tart actually dates to 1879 – before the invention of golden syrup! The recipe is by Mary Jewry and is a tart made up of alternating layers of pastry and treacle. The treacle here is black treacle, and this highlights the problem in researching the origins of this pudding; treacle meant any viscous syrup that was a byproduct of sugar refinery and specifics are not always pointed out, even after golden syrup became popular. The other problem is the recipe Mary Jewry gives is nothing like the beloved treacle tart from our childhood.

The terrifying Childcatcher from Chitty Chitty Bang Bang

coaxing the children with shouts of “treacle tart! All free today!”

Shudder.

Prior to the 17th century, treacle was used as a medicine; it was considered very good for the blood and was therefore used in antidotes to poisons. It starts cropping up in recipes for gingerbread in the mid-18th century. Jane Grigson mentions a gingerbread recipe from 1420 in her book English Food where spices and breadcrumbs were mixed together with plenty of honey to make a gingerbread that seems pretty similar a modern treacle tart, but without the pastry. Heston Blumenthal in his book Total Perfection also mentions a 17th century ‘tart of bread’ where bread and treacle are mixed with bread, spices and dried fruit and baked in an open pastry shell. Then just to complicate things further, Jane Grigson mentions that the predecessor to the treacle tart is the sweetmeat cake – again a 17th century invention – that uses candied orange peel, sugar and butter as a filling and no treacle or bread whatsoever!

All this confusing history waffle is giving me a headache. Here’s the recipe that I use for a treacle tart. It is adapted from Nigel Slater’s. I like it (and I have tried several recently) because it has a lot more bread in it than most other recipes – treacle tart should be chewy with a hint of and must hold its shape when cut, many recipes fail in this respect. I use brown bread crumbs – it gives a good flavour and increases the chewiness level a little further.

There’s a pound and a half of golden syrup in this tart so the sweetness really needs cutting with some lemon juice and zest, and if you like, a tablespoon or two of black treacle; it’s not just a nod to treacle tarts of the past, its bitterness really does tone down the sweetness. This tart makes enough for ten people I would say. Be warned – if you go for some seconds, you may fall into some kind of sugar-induced diabetic coma…

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

For the pastry

4 oz salted butter or 2 oz each butter and lard cut into cubes and chilled

8 oz plain flour

3 tbs chilled water

For the filling

1 ½ lbs golden syrup

2 tbs black treacle (optional)

juice and zest of a lemon

10 oz white or brown breadcrumbs

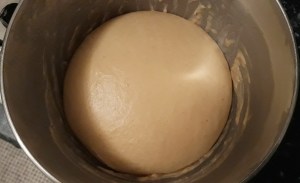

The pastry is a straight-forward shortcrust. Rub the fat into the flour with your fingertips, a pastry blender, the flat ‘K’ beater of a mixer or blitz in a food processor. Mix in two tablespoons of water with your hand and once incorporated, add the last tablespoon. The pastry should come together into a ball. Knead the dough very briefly so that it is soft and pliable. Cover with clingfilm and put in the fridge to have a little rest for 30 minutes or so.

Now roll out the pastry and use it to line a 9 inch tart tin. Put back into the fridge again – you don’t have to do this step, but sometimes the pastry can collapse a bit when it goes in the oven at room temperature.

Whilst the pastry is cooling, get on with the treacle filling. Treacle can be a tricky customer: weigh it out straight into a saucepan on tared scales and then pour the golden syrup straight in. Add the black treacle if using. Place the pan over a medium heat and stir until it becomes quite runny, then stir in the lemon juice and zest and the breadcrumbs.

Pour this mixture into the lined tart tin and bake in the oven at 200⁰C (400⁰F) for 15 minutes, then turn the heat down to 180⁰C (350⁰F) for another 15 or 20 minutes.

Best served warm with cream, ice cream or custard.