In this episode of the podcast, I talk with ceramics expert Paul Crane FSA about the early years of Worcester porcelain. Paul is a consultant at the Brian Haughton Gallery, St James’s, London, and a specialist in Ceramics from the Medieval and Renaissance periods through to the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. He presently sits as a Trustee of the Museum of Royal Worcester and is also a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, an independent historian and researcher and a Liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Art Scholars.

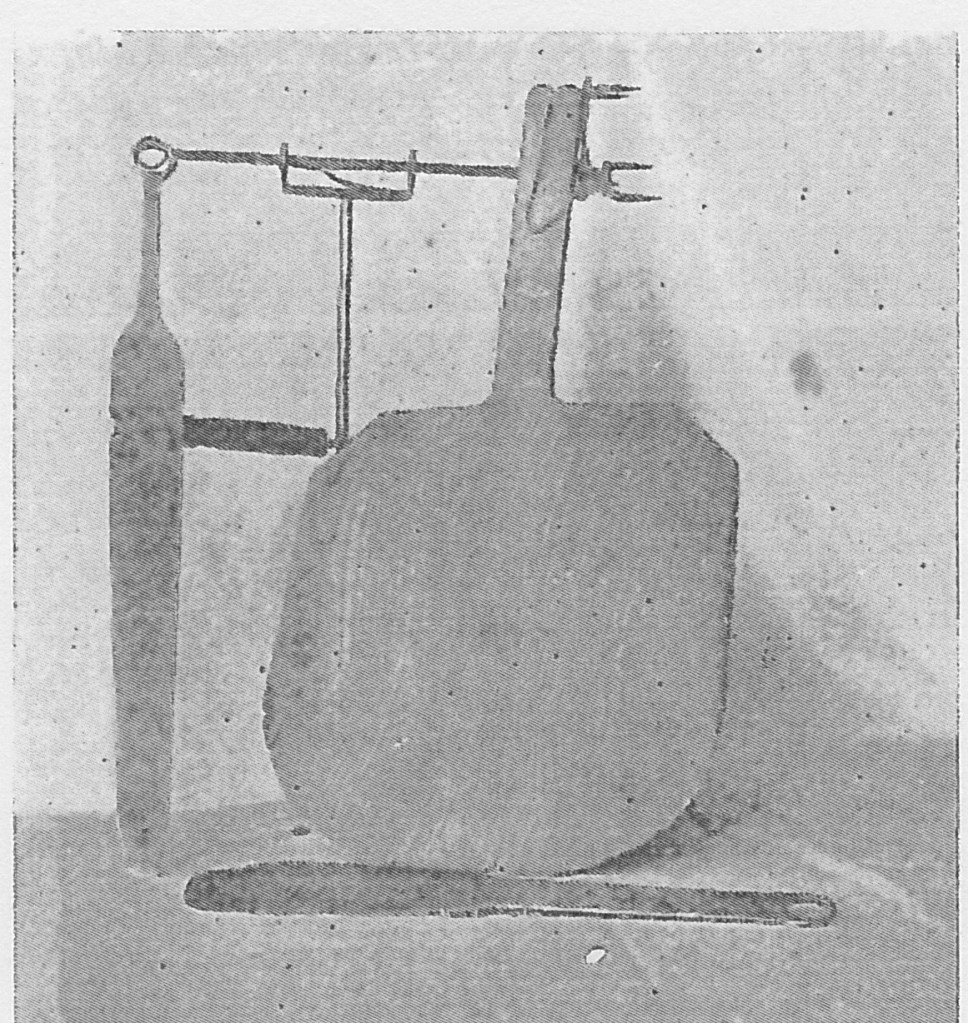

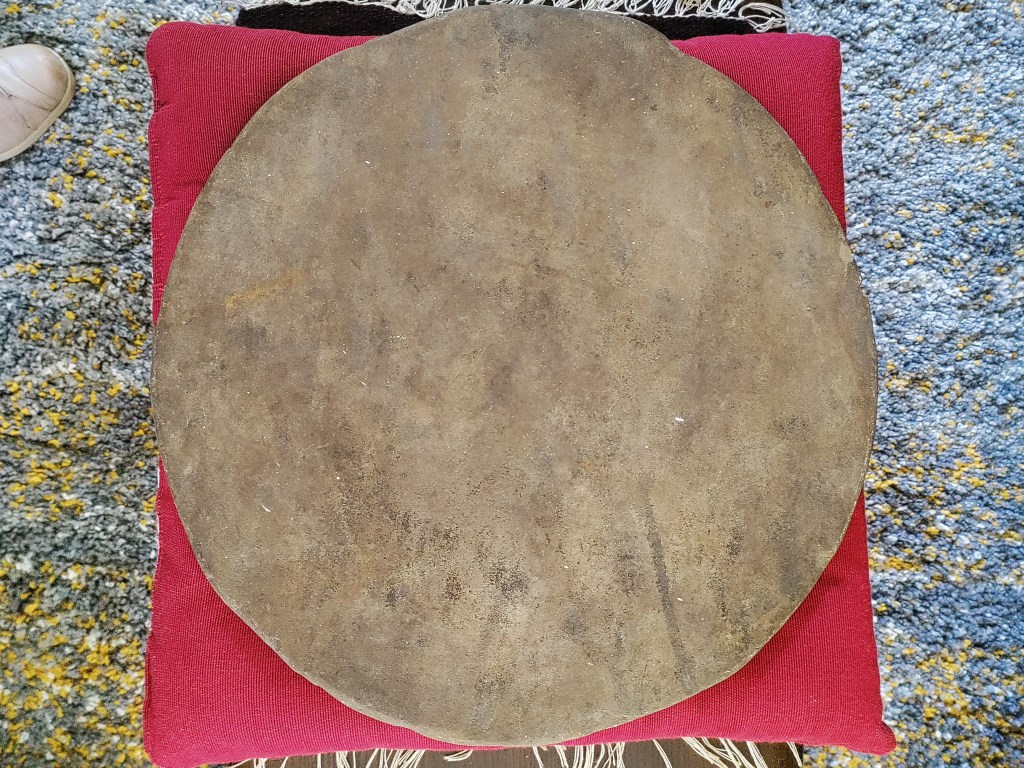

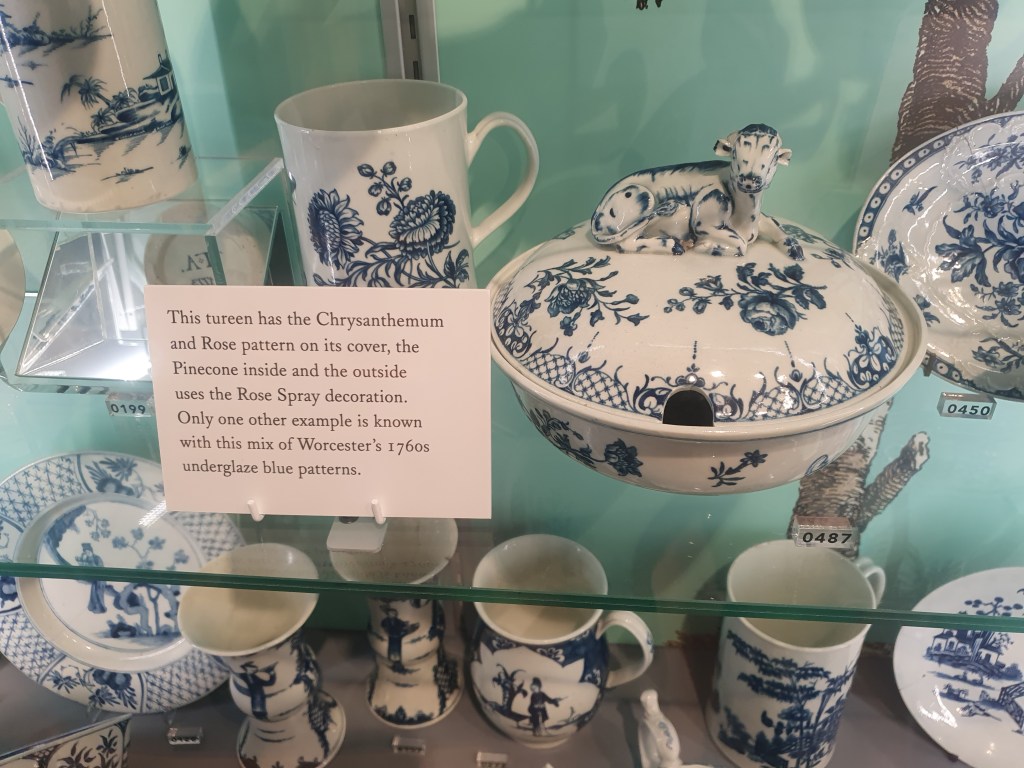

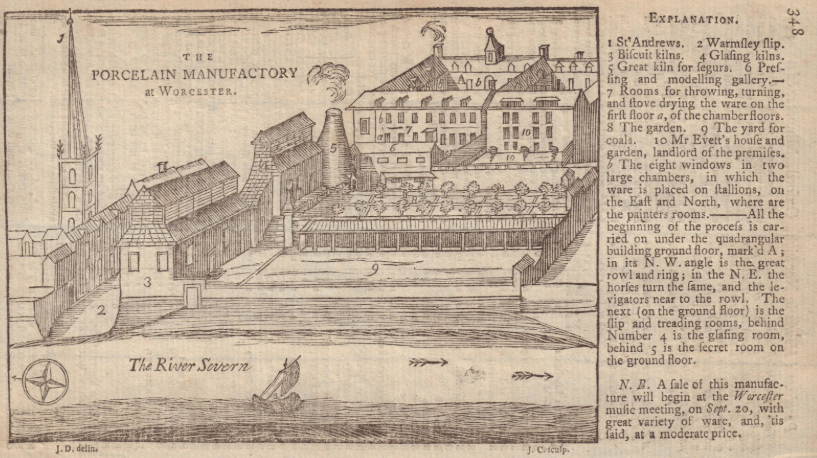

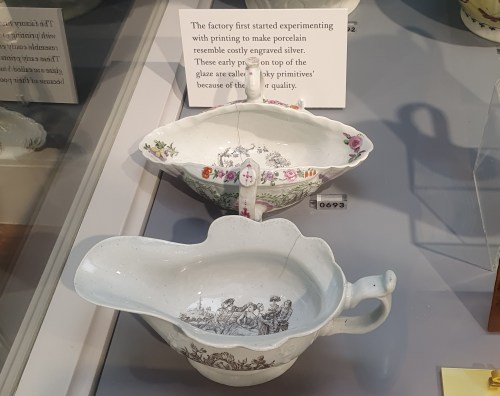

Our conversation was recorded in person at the Museum of Royal Worcester. If you want to see the pieces we discuss, check out this post where I’ve added images of the majority of the items discussed or go to the YouTube channel where I’ve lined up the images with our discussion. Paul and I really do our best to describe the pieces, but of course, it’s best if you can see them for yourself.

The images used are a mixture of my own and those taken from the Museum of Royal Worcester archives. Thank you to the museum for the permission to use them.

The podcast is available on all podcast apps, just search for “The British Food History Podcast”, or stream on this Spotify via this embed:

Alternatively, watch this episode on YouTube to see the images below matched up with the sound.

We talk about Dr Wall and how he got the Worcester manufactory up and running, the importance of seeing porcelain by candlelight, asparagus servers, the first piece of porcelain you see when you walk into the museum, the Royal Lily service and how Worcester porcelain attained the Royal warrant, amongst any other things.

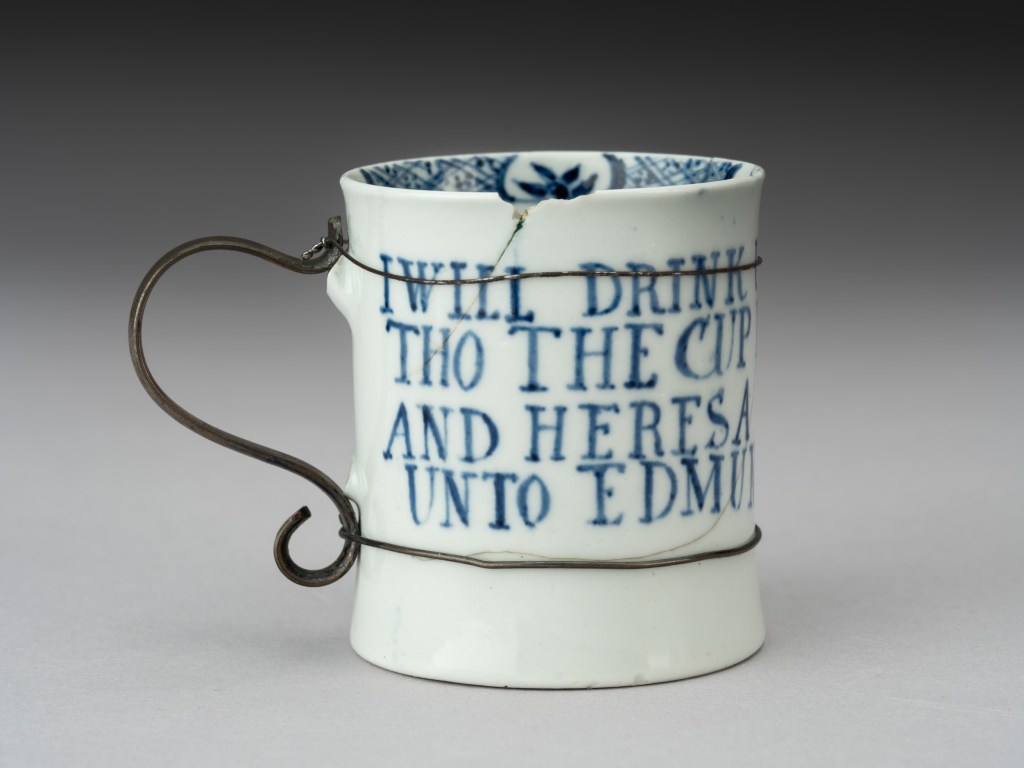

Those listening to the secret podcast can hear more about the early blue and white pieces, including a rare bleeding bowl, the first commemorative coronation porcelain mug and the stunning Nelson tea service, plus much more.

Remember: Fruit Pig are sponsoring the 9th season of the podcast, and Grant and Matthew are very kindly giving listeners to the podcast a unique special offer 10% off your order until the end of October 2025 – use the offer code Foodhis in the checkout at their online shop, www.fruitpig.co.uk.

If you can, support the podcast and blogs by becoming a £3 monthly subscriber, and unlock lots of premium content, including bonus blog posts and recipes, access to the easter eggs and the secret podcast, or treat me to a one-off virtual pint or coffee: click here.

This episode was mixed and engineered by Thomas Ntinas of the Delicious Legacy podcast.

Things mentioned in today’s episode

YouTube video of the episode with images of the porcelain discussed

Museum of Royal Worcester website

Paul’s YouTube talk called ‘Nature, Porcelain and the Enlightenment’

Paul’s YouTube talk called ‘Early Worcester from Dr Wall to James Giles’

My museum talk about Worcester porcelain and 19th-century dining

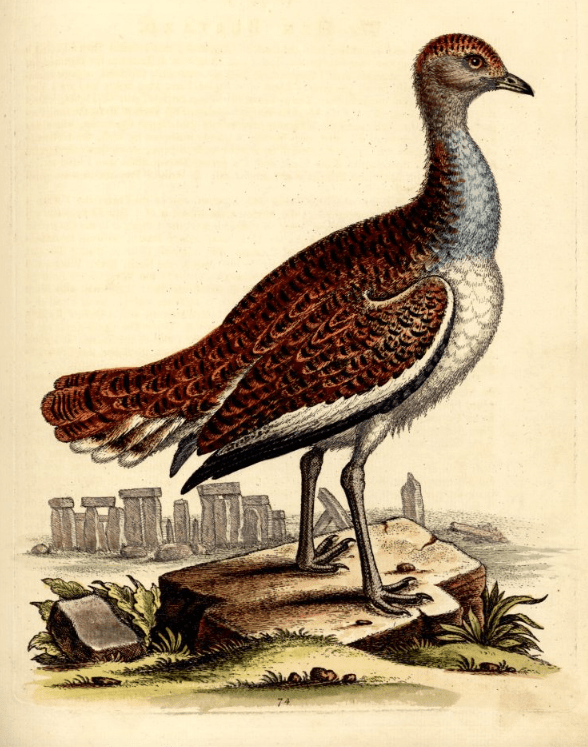

The Natural History of Uncommon Birds by George Edwards

A video about the first project Neil took part in with the Museum of Royal Worcester

Serve it Forth website – You can still receive 25% off the ticket price using the code SERVE25 at the checkout!

Serve it Forth Eventbrite page

Previous pertinent podcast episodes

18th Century Dining with Ivan Day

Neil’s other blog and YouTube channel

The British Food History Channel

Neil’s books

Before Mrs Beeton: Elizabeth Raffald, England’s Most Influential Housekeeper

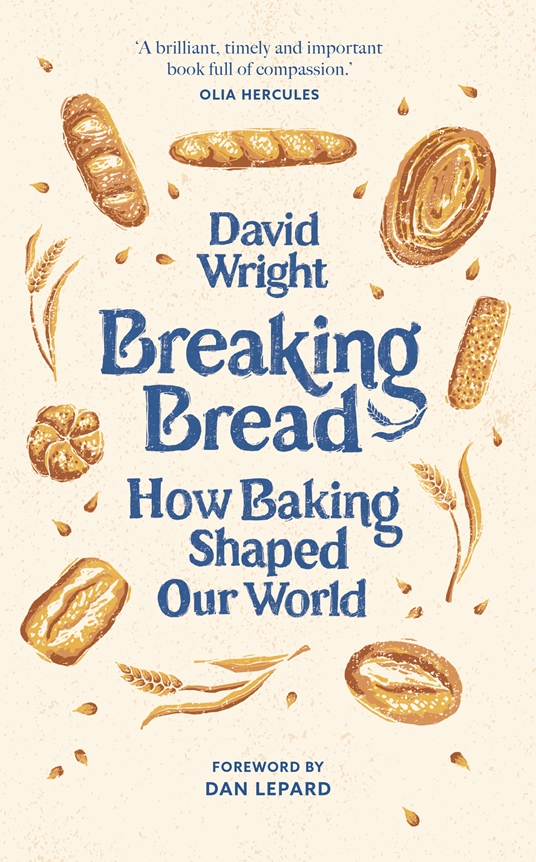

Knead to Know: a History of Baking

Don’t forget, there will be postbag episodes in the future, so if you have any questions or queries about today’s episode, or indeed any episode, or have a question about the history of British food, please email me at neil@britishfoodhistory.com, or leave a comment below.