Merry Christmas everyone!

It’s time for my annual Yuletide boozy drink post. This year: lambswool, a drink very much associated with the Wassail on Twelfth Night (the night before Epiphany, 6 January, and the last day of Christmastide). It has been drunk since at least Tudor times – I cannot find any descriptions prior to the late 16th century. It’s a type of mulled ale, and this description by Robert Herrick in his poem Twelfth Night: Or King and Queen (1648) is a very good one:

Next crowne the lowle full

with gentle lamb’s wool;

Adde sugar, nutmeg and ginger;

with a store of ale too;

and thus ye must doe

to make the wassaille a swinger.[1]

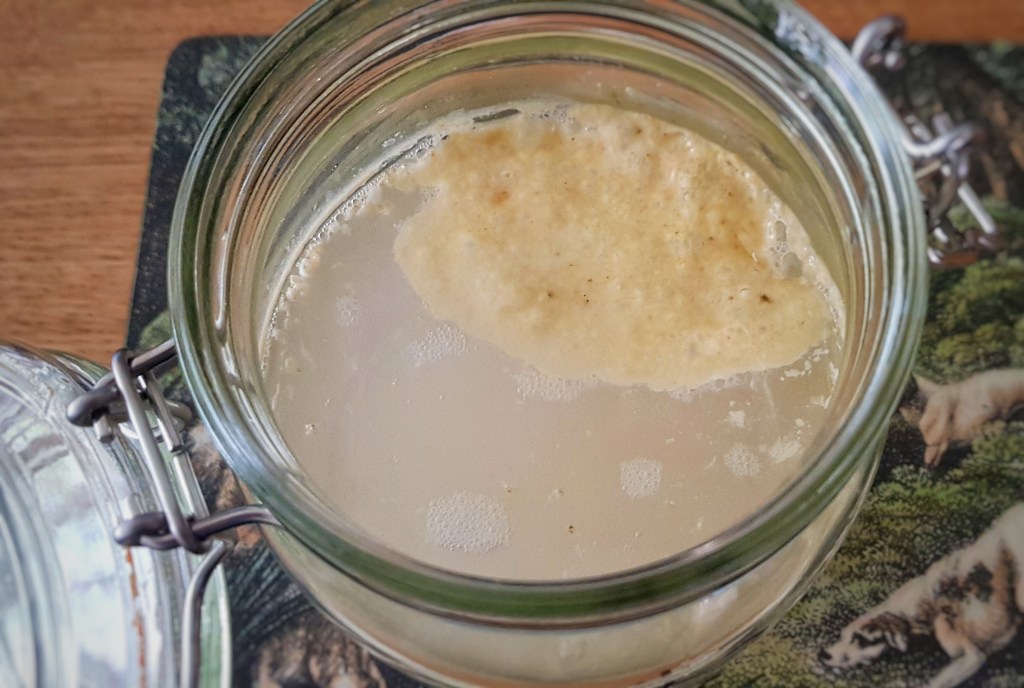

What Henrick doesn’t tell us is that there is cooked apple floating on the top which break apart, hence the name lambswool. These apples are, in the early modern period, generally roasted crab apples, so very sour in flavour, though in later recipes such as the lambswool described by Peter Brears in Traditional Food in Yorkshire, made in Otley, West Yorkshire in 1901, dessert apples are used. They were cored and cooked and floated in the drink, then fished out and eaten separately.[2] Spiced cakes and mince pies were also eaten.[3]

Many drinks were laced with rum or brandy and often enriched with eggs, cream or both,[4] such as this one here for ‘Royal Lamb’s Wool’, dated 1633: ‘Boil three pints of ale; – beat six eggs, the whites and yolks together; set both to the fire in a pewter pot; add roasted apples, sugar, beaten nutmegs, cloves and ginger; and, being well brewed, drink it while hot.’[5] Before the lambswool was poured into the Wassail cup sliced of well-toasted bread sat at the bottom. With the apple floating on top, this was basically a full meal. Nice and full, it was then passed around, everyone taking a sup from the communal bowl. I prefer to ladle it into separate glasses or mugs – and I am sure my guests would be pleased with this decision.

Lambswool drinking was not restricted to Twelfth Night, or even Christmastide, as this entry from Samuel Pepys’ diary dated the 9th of November 1666 informs us: ‘Being come home [from an evening of dancing], we to cards, till two in the morning, and drinking lamb’s-wool. So to bed.’[6]

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

Recipe

I have to admit, I was unsure about the lambswool, but it was delicious. I think that it should come back, and it is certainly much, much nicer than bought mulled wine. Recipes don’t necessarily specify the type of sugar, but I think light brown sugar really complements the maltiness of the beer well.

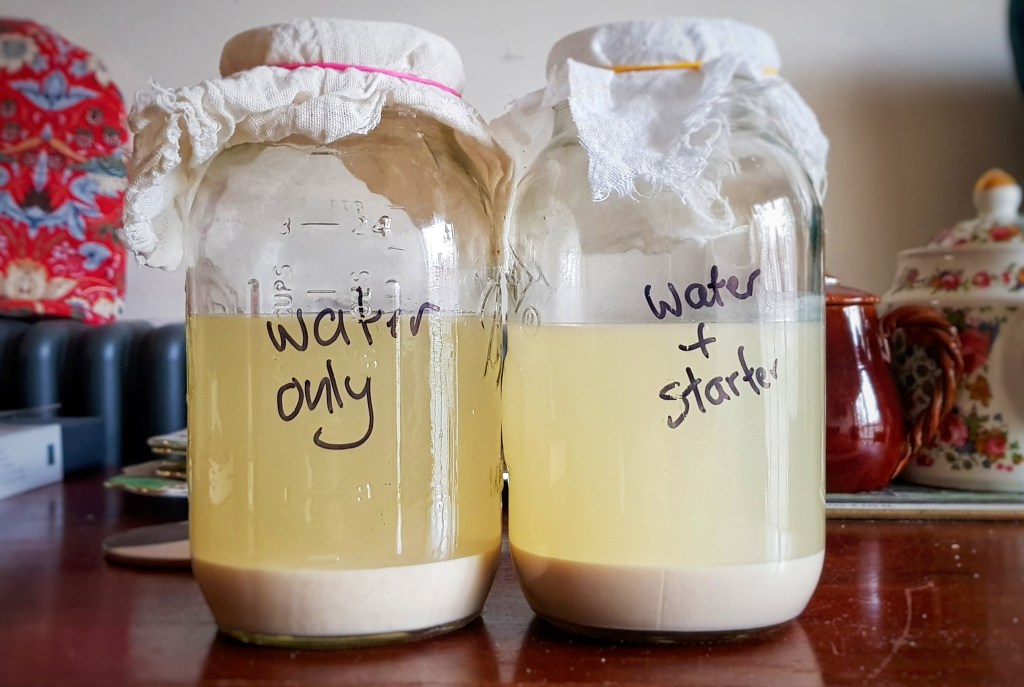

A note on the beer: trendy IPAs and other craft beers are far too hoppy for this recipe – I think there’s a flavour clash, so make sure you go for a low-hop traditional brown ale. I used Old Speckled Hen (which is available to buy gluten-free, by the way). The best – and, dare I say it – most authentic choice would be an unhopped ale, but I have never come across one! Add cream and eggs if you think it matches your own tastes: I have to admit that as an eating/drinking experience, the creamy texture worked better with the pureed apple than the version without.

I used dessert apples for the wool, but you can use crap apples if you want to be true to the early modern period, or Bramley’s Seedlings, which do have the benefit of breaking down to a nice fluff. I discovered that it’s very difficult to get your apples to float on top, but this is not of great importance. Sam Bilton has an ingenious way of getting her apple puree to float though, and that is to fold a whipped egg white into the cooked apple puree.[7]

Makes 6 to 8 servings

6 small to medium-sized dessert apples

Caster sugar to taste (optional)

2 x 500 ml bottles of brown ale

120 – 140 g soft dark brown sugar

2 cinnamon sticks

8 cloves

1 tsp ground ginger

120 ml dark rum or brandy

4 eggs (optional)

300 ml cream (any kind will do; optional)

To serve: freshly-grated nutmeg

Start by making the apple purée: peel, core and chop the apples and place in a small saucepan with a few tablespoons of water, cover, turn the heat to medium, and cook until soft. If the apples don’t break down naturally, use the back of a wooden spoon. Add caster sugar to taste – if any is needed at all.

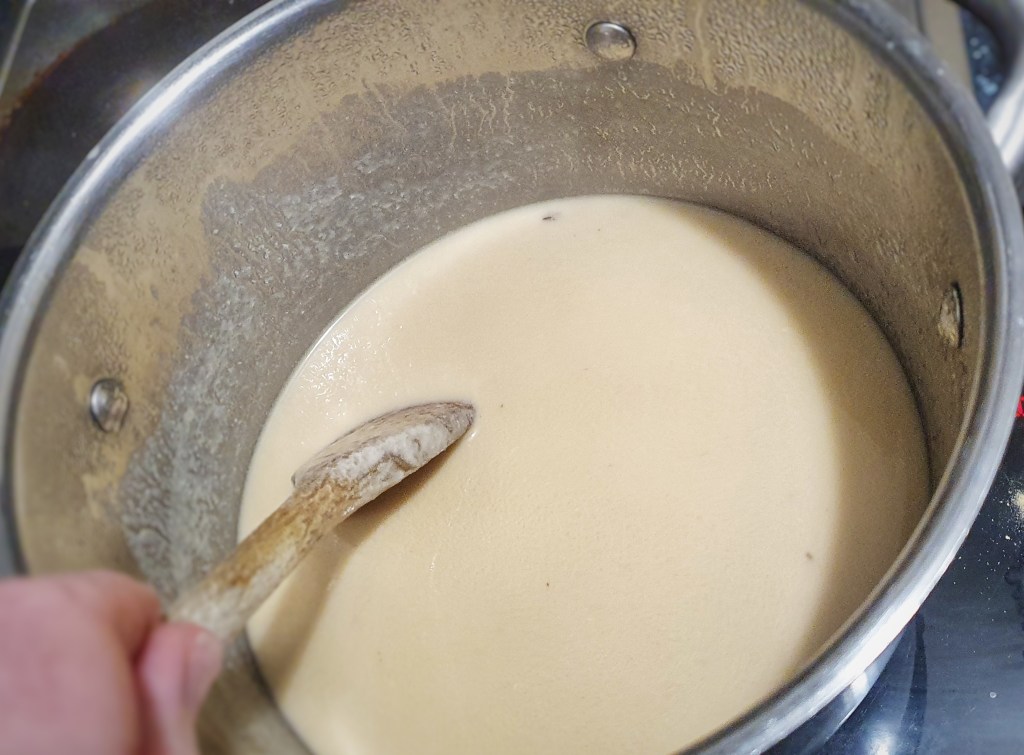

Whilst the apples are cooking down, pour the beer into a saucepan, add 120 g of soft dark brown sugar if making the non-creamy/eggy version, or add 140 g if you’re intrigued by it! Snap the cinnamon sticks and chuck those in along with the other spices. Turn the heat to medium and let it all get nice and steaming-hot; you don’t want it to boil, otherwise you’ll lose a lot of the alcohol. Leave for 10 minutes so the spices can infuse, then add the rum or brandy. Let it come back up to heat for another five minutes. If you don’t want to make the custardy version, the lambswool is ready, and it can be ladled out into glasses or mugs and top with a couple of spoons of the warm apple purée and a few raspings of freshly-grated nutmeg.

For the custardy version: after you add the brandy or rum, whisk the eggs and cream in a bowl, take the lambswool off the heat, and pour three or four ladlefuls of it into the cream and egg mixture, whisking all the time. Now whisk this mixture into the lambswool, and stir over a medium-low heat until it thickens. If you want to use a thermometer to help you, you are looking to reach a temperature of 80°C. Pass the whole lot through a sieve and into a clean pan, and serve as above.

Notes

[1] Herrick, Robert. Works of Robert Herrick. vol II. Alfred Pollard, ed., London, Lawrence & Bullen, 1891.

[2] Brears, P. (2014) Traditional Food in Yorkshire. Prospect Books.

[3] Brears (2014); Crosby, J. (2023) Apples and Orchards since the Eighteenth Century: Material Innovation and Cultural Tradition. Bloomsbury.

[4] Hole, C. (1976) British Folk Customs. Hutchinson Publishing Ltd.

[5] Though quoted in many places, I could not find the source of this recipe – but the reigning monarch was Charles I

[6] Diary entries from November 1666, The Diary of Samuel Pepys website https://www.pepysdiary.com/diary/1666/11/.

[7] Bilton, S. (2025) Much Ado About Cooking: Delicious Shakespearean Feasts for Every Occasion. Hachette UK.