Welcome to the first episode of season 9 of The British Food History Podcast! I am going to be adding a blog post to complement each new episode of the podcast, to help readers of the blog keep tabs on what is going on.

Today I am talking with Matthew Cockin and Grant Harper of Fruit Pig – the last remaining commercial craft producer of fresh blood black puddings in the UK.

Fruit Pig are sponsoring the 9th season of the podcast and Grant and Matthew are very kindly giving listeners to the podcast a unique special offer 10% off your order until the end of October 2025 – use the offer code Foodhis in the checkout at their online shop, www.fruitpig.co.uk.

We talk about how and why they started up Fruit Pig, battling squeamishness, why it’s so difficult to make fresh blood black puddings, and serving suggestions – amongst many other things

The podcast is available on all podcast apps, aandd now YouTube. Please give it a follow, and if you can, please rate and review. If you’re not a podcasty person, you can listen via this Spotify imbed:

Some serving suggestions

One other thing we talked about was serving suggestions, and of course a slice or two of black and white pudding as part of a full English breakfast is admirable. You can go one better and have the full triple of black pud, white and haggis for a full Scottish! Personally, I believe a slice of fried bread topped with a couple of slices of fried pudding and a poached egg is the breakfast of champions.

These puddings are not just for breakfast, though. In Lancashire, a favourite way of eating black pudding is to poach it again, remove it from the water, drain, split lengthways and spread it with mustard. I have eaten it this way when visiting Bury Market. But my favourite way of eating black and white pudding in a simple way, is to serve fried slices of pudding with mashed potatoes and apple sauce – hot or cold, not too sweet. Here’s how to make a good ‘savoury’ apple sauce:

Peel, core and slice 2 medium-sized Bramley apples, and 2 tart dessert apples (e.g. Cox’s Orange Pippin) and fry in a saucepan with 60 g salted butter and a good few grinds of pepper. When the Bramleys start to soften, add 2 level tablespoons of sugar and 4 or 5 tablespoons of water. Cover and cook on medium heat, stirring occasionally, until the apples are cooked through and the Bramleys have broken down to a puree. Taste and correct seasoning. You need something still very tart to cut through the rich puddings.

Keep a lookout for a proper recipe and some of my experiments with the fresh blood, Matthew and Grant kindly sent me.

If you can, support the podcast and blogs by becoming a £3 monthly subscriber, and unlock lots of premium content, including bonus blog posts and recipes, access to the easter eggs and the secret podcast, or treat me to a one-off virtual pint or coffee: click here.

This episode was mixed and engineered by Thomas Ntinas of the Delicious Legacy podcast.

Things mentioned in today’s episode

Fruit Pig on Jamie & Jimmy’s Friday Night Feast

Fruit Pig on BBC Radio 4’s The Food Programme

Neil’s appearance on Comfortably Hungry discussing black/blood pudding

Museum of Royal Worcester project wins a British Library Food Season Award

Follow Serve it Forth on Instagram at @serveitforthfest

Podcast episodes pertinent to today’s episode

The Philosophy of Puddings with Neil Buttery, Peter Gilchrist & Lindsay Middleton:

18th Century Female Cookery Writers with The Delicious Legacy:

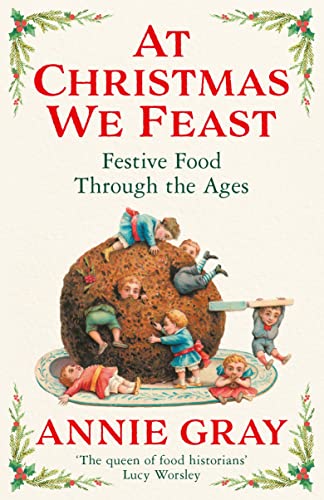

Neil’s books:

Before Mrs Beeton: Elizabeth Raffald, England’s Most Influential Housekeeper

Knead to Know: a History of Baking

Don’t forget, there will be postbag episodes in the future, so if you have any questions or queries about today’s episode, or indeed any episode, or have a question about the history of British food please email me at neil@britishfoodhistory.com, or leave a comment below.