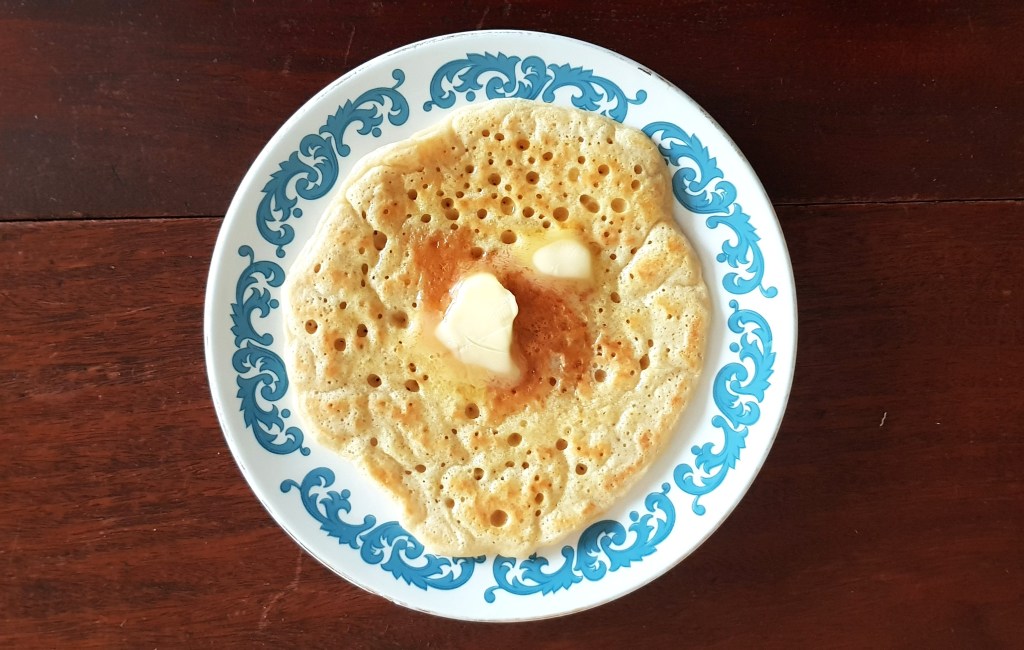

A couple of posts ago I gave you my recipe for scones. As with many foods, there is a variety of baked things that are called scones, which can cause a certain amount of confusion (see also: pudding[1], bun and cake[2]). My recipe is for what I think most people would consider a ‘proper’ scone: cakey, slightly dry and crumbly and therefore served spread with lashings of jam and butter or clotted cream. In other words, the scone one receives when ordering a cream tea. Despite its modern link with Devon and Cornwall, the scone most certainly originated in Scotland. These scones were baked not in ovens but on girdles/griddles or bakstones/bakestones, and there are two main types: those made from a runny batter and baked on a lightly greased griddle, often called drop scones today, or ‘Scotch’ pancakes outside of Scotland.[3] The second type is more cakelike; a dough that may be shaped into one large round and baked whole as a bannock, or cut into triangles as scones. The scones may also have been made by rolling out the dough and cutting out rounds. However they were shaped, these scones were cooked on a lightly-floured girdle.[4]

For more about the history of bakestones and griddlecakes see my book Knead to Know: A History of Baking, published by Icon Books.

Wheaten bread may have been used in both types of scone, but more often they were made from oats or barley and sometimes peasemeal in the very north of Scotland.[5] For delicious potato scones, some of the wheat flour is replaced with leftover mashed potatoes. Scones are typically chemically raised with bicarbonate of soda activated usually with soured buttermilk, but seeing as the word scone goes as far back as the early 16th century, this cannot have always been so; chemical raising agents were not widely available until the latter half of the 18th century. I do see recipes that use yeast and others with no leavening at all. I strongly suspect that the early scones would have been made with sourdoughs.

Recipes begin to travel south and cross the border. Jane Grigson mentions a Northumbrian scone that is made with wholewheat flour and is leavened by yeast.[6] F. Marion McNeill, writing in the 1920s observes that ‘scones [are] popular in England now, but there are no recipes in Beeton’s book’, meaning – of course – the fantastically comprehensive Beeton’s Book of Household Management of 1861.[7] There are several recipes for scones in Cassell’s Dictionary of Cookery (1883) and Robert Wells’ Pastry & Confectioners’ Guide (1892).[8] Interestingly, none of them are baked in ovens despite many homes having ovens by this point in history.

However, in Good Things in England (1932), that wonderful collection of traditional English recipes by Florence White, there are recipes for scones baked both in ovens and on griddles. A variety of flours are being used too, including oatmeal and ‘Maize or Indian Meal’.[9] Baked scones – in England, at least – quickly take over and usurp not only the griddlecake variety of scones, but also the Devonshire/Cornish split in the cream tea.[10] But in the 21st century, these baked scones move even further away from their origins – egg is added for richness, milk is used over the now tricky to find buttermilk (in combination with baking powder).

For many folk, scones will be forever associated with the south-western peninsula of England, but it is important to remember, as Catherine Brown and Laura Mason put it in The Taste of Britain (1999): ‘Few English people would appreciate that [scones are] as Scottish as oatmeal porridge.’[11] I hope you appreciate it now!

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce and would to start a £3 monthly subscription, or would like to treat me to virtual coffee or pint: follow this link for more information. Thank you.

Notes:

[1] This is discussed at length in my book The Philosophy of Puddings (2024).

[2] These are discussed in my book Knead to Know: A History of Baking (2024).

[3] These griddlecakes are also the forerunner to the sublime fluffy American pancake

[4] Buttery, N. (2024). Knead to Know: A History of Baking. Icon Books; McNeill, F. M. (1968). The Scots Kitchen: Its Lore & Recipes (2nd ed.). Blackie & Son Limited.

[5] Buttery, N. (2018, April 17). Pease Pancakes. British Food: A History.

[6] Grigson, J. (1992). English Food (Third Edit). Penguin. I have – of course – cooked this recipe as part of my Neil Cooks Grigson project all the way back in 2008. I didn’t do a very good job of it and it requires a revisit. Read the original post here.

[7] McNeill (1968)

[8] Cassell. (1883). Cassell’s dictionary of cookery. Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co.; Wells, R. (1892). The Pastry Cook & Confectioners’ Guide. Crosby Lockwood and Son.

[9] White, F. (1932). Good Things in England. Persephone.

[10] Buttery, N. (2019, October 19). Cornish Splits (& More on Cream Teas). British Food: A History.

[11] Mason, L., & Brown, C. (1999). The Taste of Britain. Harper Press.