Want to know more? There’s a podcast episode that complements this blog post:

A Simnel cake is a type of fruit cake that contains plenty of marzipan and is eaten at Easter, although it used to be specifically associated with Mothering Sunday. When folk were fasting during Lent, Mothering Sunday, appearing in the middle of the fast, offered a respite from 40 days of religious austerity.

Mothering Sunday occurs on the fourth Sunday of Lent; a special day when people visited their mother church or cathedral. Don’t confuse Mothering Sunday with Mothers’ Day; it is only in the last century that this day is associated with showing enforced appreciation to our mums (though I assume that you met up with your mother on return to your original diocese).

Like most British food eaten during winter and early spring, the Simnel cake contains lots of dried fruit, but it is much lighter than boozy Christmas cake and contains a layer or marzipan both on top and within, and is decorated with eleven marzipan balls, each symbolising Jesus’s disciples (minus the treacherous Judas of course).

To trace the origin of Simnel cake, you need to go right back to mediaeval times where it began life as a yeast-leavened bread, which may or may not have been enriched. This doesn’t sound that much like a special bread, you may think, but what made it special is that it made out of the highest quality flour possible; simnel derives from the Latin simila – the whitest and finest of flours.

Fast forward to the 17th and 18th centuries, and the bread mixture had been swapped for a pudding batter, not dissimilar to spotted dick, enriched with dried fruit, spices and almonds. It would be boiled like a pudding. When cooked, it was wrapped in pastry, glazed with egg and baked until a good hard crust formed. It would be like the Scottish black bun, a traditional Christmas food north of the border.

It is only when you get to the tail end of the 19th century that it starts to look like something we would recognise as a cake, though surprisingly it is not until the 20th century that the familiar marzipan layers and decorative disciples appear.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

Simnel cakes themselves seem to be disappearing from our Easter tables altogether and are getting more and more difficult to find in British bakeries. Below is the recipe I use – I can’t claim it as my own, but I don’t know where I got it from, so if you recognise it let me know, you know I always like to credit my sources!

This is a very straight-forward cake mixture made using the all-in-one method; it is very important that you use very soft butter so that the cake batter creams quickly without developing the gluten too much. If you don’t want to make your own marzipan, you can buy some ready-made, but I do urge you to make your own, it really is worth the (really quite little) effort required. The marzipan recipe below is different to my previously published one and I think much better. I shall try to remember to update the other post.

For the cake:

225 g softened butter

225 g caster sugar

4 eggs

225 g plain flour

2 tsp ground cinnamon

zest of 2 oranges

zest of 2 lemons

325 g mixed fruit (currants, sultanas, currants)

125 g glacé cherries, quartered or left whole

500 g orange marzipan (see below)

icing sugar for dusting

apricot jam

1 beaten egg

Begin by greasing and lining an 8-inch cake tin and preheating your oven to 150°C.

In a large bowl, beat together the softened butter, caster sugar, eggs, flour, cinnamon and zests. Using a hand mixer, beat together until smooth. Now fold in the mixed fruit and cherries with a spatula or wooden spoon.

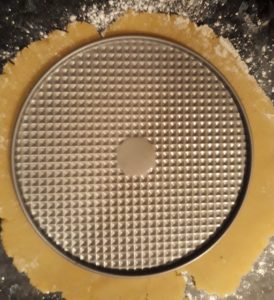

Spoon half of the mixture into your tin and level it off. Take a third of your marzipan and roll it out into a circle the same size as the tin, trimming away any untidy bits. Use a little icing sugar to roll the marzipan out, just like you would use flour to roll out pastry.

Lay the marzipan in the tin and then spoon and scrape the remainder of the cake batter on top of that. Level off with your spatula and make an indentation in the centre, so that the cake doesn’t rise with too much of a peak.

Bake for 2 ¼ to 2 ½ hours. Use a skewer to check it is done. Cool on a rack for about 30 minutes before removing the tin and greaseproof paper.

When cold, roll out half of the marzipan in a circle slightly larger than the cake – the best way to do this is to use the outside edge of the tin it was baked in as a template.

Brush the top of the cake with some apricot jam (if it is very thick, you may want to warm some with a little water in a pan) and lay the marzipan on top, then brush the marzipan with the beaten egg. Divide the remaining marzipan and trimmings into 11 equally-sized balls and arrange them in a circle. Brush those with egg too and glaze the top using a chef’s flame torch (or a very hot grill).

For the marzipan:

90 g caster sugar

140 g icing sugar

220 g ground almonds

grated zest of an orange

1 beaten egg

Mix all of the ingredients except for the egg in a bowl. Make a well in the centre and pour in the egg. Using a mixer or your hand, form a dough. Knead in the bowl until smooth, wrap in cling film and refrigerate for at least 2 hours.

Do you like the blogs and podcast I produce? If so, please consider supporting me